Lessons of corporate giving

Philanthropy has always been a transformative aspect of society, but some campaigns are more successful than others

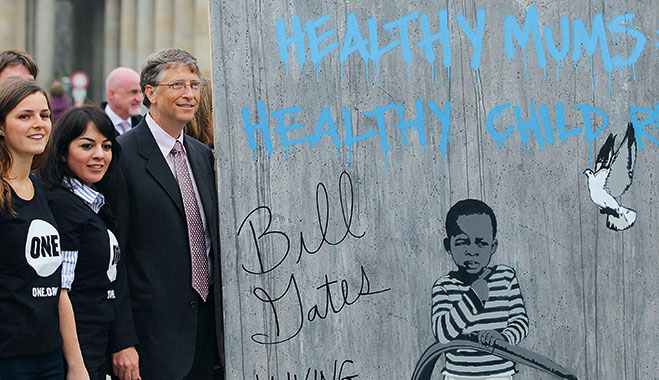

Bill Gates poses with charity volunteers during a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation campaign in Pariser Platz Square, Berlin

As the already colossal wealth gap across the world continues to grow, fuelling distrust and resentment from the poorest on the planet towards those lucky few with all the money, many observers are calling for a new age of philanthropy that could help provide for those who are worst off.

However, there is a debate about how members of the super-rich with philanthropic tendencies should deploy their wealth and what level of involvement they should take. Many of those successful businessmen with money to donate aren’t convinced of the not-for-profit organisation’s ability to deliver proper results.

The US has the highest rate of donors compared to its GDP

It isn’t just the poor who benefit from philanthropy. The wealthy often provide the capital for innovative projects that would otherwise struggle to receive long-term funding. From the donations of around $183m each year by Intel founder Gordon Moore and his wife, to green technologies and the backing of the arts by English sugar merchant Sir Henry Tate. In the US alone, as much as $300bn a year is donated to maintaining advanced medical research, education and the arts, and tackling poverty.

According to the UK’s Philanthropy Impact research group, the US has the highest rate of donors compared to its GDP, with 2.2 percent given each year. This is followed by the UK, at 1.1 percent, the Netherlands with 0.9 percent and Germany with 0.7 percent.

Noble causes

Philanthropy has always been an integral part of society, with the richest using their money to transform their communities – sometimes with grandiose plans for a legacy, but often through genuine care for those less fortunate than themselves.

May saw celebrations marking the centenary of the Rockefeller Foundation, one of the most ambitious and successful examples of a philanthropic cause instigated by one man. John D Rockefeller proposed that his organisation would use his staggering wealth – he was the world’s richest man at the time, with what would be $663bn in today’s money – to “promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world”. Its early achievements included helping the American Red Cross form, and paying for the University of Chicago (with $35m in donations) and the Harvard School of Public Health.

Rockefeller’s example has been taken up by some of today’s leading businessmen, from financiers George Soros and Warren Buffett, to Microsoft pioneer Bill Gates. But the fact they are getting so much attention for their hugely generous plans perhaps shines a light on the lack of grand philanthropic gestures over the last few decades.

Many philanthropists tend to build vast levels of wealth within a particular industry, and go on to use those riches to help in the development of that sector. Los Angeles-based Professor Patrick Soon-Shiong, who invented the widely used cancer drug Abraxane, has built a fortune of around $7.2bn. Much of that wealth is used to fund health-related projects, such as a $135m donation to Santa Monica’s Saint John’s Health Centre.

Others dedicate their money to causes they are particularly passionate about. Hewlett-Packard founder William Hewlett, media mogul Ted Turner and venture capitalist David Gelbaum have all dedicated vast sums to developing green technologies that might otherwise not have received funding due to their relatively high risk.

Soros has also consistently donated portions of his wealth to social causes, such as aiding students in South Africa, promoting democracy in the former Soviet states, and science and education projects across the US and Europe.

Leaving a legacy

It is the Giving Pledge campaign, spearheaded by Buffett and Gates, that is being heralded by many as the catalyst for the new age of philanthropy. Set up in 2009, the campaign encourages the world’s richest people to give the majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes and has so far signed up 105 billionaires worldwide.

The campaign does not stipulate for what causes the money can be used, but encourages donors to put their wealth to use either during their lifetime or after their death. For example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – which has also received considerable donations from Warren Buffett – has ambitious plans to eradicate polio, AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. It was reported to have received $36.2bn towards the end of 2012.

Business thinking will push resources away from the poorest people

While Rockefeller’s philanthropic goals were active long after his death, the Gateses have clearly stipulated that all their money must be deployed within 50 years of theirs. They specifically want to see benefits within their lifetime and feel that, by taking a more active role in how it is spent, they can make a bigger difference.

Both strategies show plans for grand legacies, but philanthropists with a clear goal of what they want their money to achieve – and during their lifetime – perhaps show less of a concern for an egotistical legacy long after their deaths and a greater desire to make a significant improvement to the world around them.

Tax breaks

Many of the world’s most notable philanthropists are often accused of throwing money at charitable causes as a means to assuage their corporate guilt and improve their public profiles. Some are also accused of using philanthropy as a means to cut their tax requirements. This accusation is enthusiastically levelled at large corporations that trumpet their charitable endeavours, but which tend to neglect to mention the considerable tax breaks they receive from governments for doing so.

Tax laws in a number of countries allow those who donate certain amounts of money each year to claim back some of their taxes as a result of philanthropy. In the UK, for example, people who pay a tax rate of 40 percent are able to reclaim 25 percent of every pound they donate to charity. In the US, there are similar incentives towards charitable donations.

As the financial crisis has forced governments to try to claw back as much money as possible in tax, some are looking at reforming their rules for charitable giving. In the US, President Barack Obama has attempted to limit the tax deduction for charitable giving to 28 percent of the value of the donations, while UK Chancellor George Osborne attempted a similar cap in last year’s budget. Both have failed to pass these reforms, with non-profit organisations successfully arguing that tax incentives are integral to encouraging the wealthy to donate to good causes.

One individual often accused of squirreling away his large fortune overseas is British peer Lord Michael Ashcroft. After much speculation over where he paid his taxes – a concern considering the amount of money he donates to the UK’s Conservative Party – Lord Ashcroft was forced to admit to being a non-domiciled citizen, with much of his money held in accounts in Belize. However, Lord Ashcroft recently announced plans to sign up to the Giving Pledge, which will see at least half of his £1.2bn fortune given to philanthropic causes.

The business of charity

While it is easy to be cynical about a business that has philanthropy as part of its strategy, many companies do so with good intentions. It is hard to argue against Microsoft’s training initiatives of recent years, which have tried to help out-of-work people back into employment.

The link between businesses and philanthropy also presents an interesting opportunity for an improvement in how donations are deployed. There is concern from many people who have built their fortunes from savvy business strategies that charities and philanthropic endeavours don’t offer the sort of targeted returns on investment that they are used to.

Obviously, charitable causes are not going to be giving a financial return, but in some cases those donating don’t see any clear results come from the money they’ve given. The question of whether charities should be run more along the lines of a business has been hotly debated.

In a discussion for the Wall Street Journal in 2011, Charles Bronfman and Jeffrey Solomon – philanthropists and co-authors of the donation guidebook The Art of Giving – said charities should be run much more in the style of a business in order to be more effective. They said: “To have a sustained and strategic impact, philanthropy must be conducted like business – with discipline, strategy and a strong focus on outcomes.”

They added: “Focusing on efficiency and outcomes is an approach that works for any kind of charity, including those that help the very poor. Whatever the mission, there still has to be a balance between revenue and expenses, and goals must be set and met for funding to continue.”

Dreams and plans

Examples of a successful blending of philanthropic ambitions with business-like knowhow are often found in family offices. These firms – of which the Rockefeller Foundation could be described as an early form – often have philanthropy as an integral part of their portfolios. This can take the form of any particular pet project of a wealthy family, with an obvious example being Fleming Family & Partners’ impressive support of the arts.

However, Michael Edwards of research group Demos argues philanthropic organisations are different from businesses and should be treated as such: “Let’s not forget the reason we have philanthropy in the first place. It’s to support work that will never be funded or supported effectively by the market or government. By definition, too much business thinking will push resources away from the poorest people, the most difficult problems, and the most important solutions – which tend to be costly, complex and slow in coming.”

Bronfman and Solomon are adamant that, without a clear business strategy, philanthropic campaigns are merely wasting money: “Dreams without plans remain dreams. Dreams with plans become reality.” However, Edwards counters, saying: “Martin Luther King had a dream, not a business plan, yet the civil rights movement changed the world.”

Evidently, philanthropy is going through an interesting phase. With such a gap in wealth between richest and poorest, those better off are expected to help those who aren’t. More targeted approaches, taking the experience of business, should also help in the success of philanthropic projects, as would the hands-on approach of experts like Bill Gates and Warren Buffett.

Whether a new age of philanthropic giving is about to dawn remains to be seen. Certainly, examples like the Giving Pledge are noble and somewhat surprising campaigns on behalf of the super-rich. What could emerge as a result of such initiatives is a new understanding between rich and poor; where those less well off are less concerned with the increasing wealth gap, provided the extremely wealthy have grand philanthropic ambitions for that money. In order for this to happen, however, there needs to be some obvious success stories as a result of the giving, rather than just high-profile PR campaigns.