Print and prosper – 3D printing takes over

3D printing is advancing rapidly and the technology’s promise is enormous. However, is this audacious experiment set to underwhelm, or is it set to spark a second industrial revolution?

To the unenlightened, 3D printing may seem like a novelty, but before long the technology might be no more unique than conventional printing at home. Science fiction-style labs are springing up filled with highly skilled engineers trying to harness 3D printing. The technique itself isn’t particularly new and has been used for over three decades under the term ‘rapid prototyping’. Yet what is remarkable is how much the manufacturing process has developed since the turn of the 21st century. Since 2003, sales of printers have increased significantly while prices have plummeted proportionally. Currently, a printer for personal use can be picked up for £500, while commercial variants are typically priced between £1,000-£2,000.

Domestically, these portable factories invite the user to launch their own manufacturing hub, making anything from mobile phone cases through to toys and Christmas decorations. The type of item that has come to symbolise the movement on a domestic level is the humble clothes peg. The amount of work that now goes into the production of the ubiquitous household item spans an entire logistical chain; producing a cluster of clothes pegs from home as and when the need arises will cut unnecessary production and transportation costs. Thus, the clothes peg owner’s carbon footprint will be improved significantly and a further green benefit associated with domestic 3D printing use is that it can be employed to run repairs, which goes hand∞in∞hand with the recession-apt trend, “make do and mend”.

At the forefront

Areas associated with the 3D printing phenomenon are diverse in kind and extend well beyond conventional bathroom hooks and clothes pegs. Medicine is an industry that is steadily relying on additive manufacturing techniques, which is the more descriptive term for what is now referred to as 3D printing. The technology can be applied to a range of medical facets, one of the most important being the production of surgical guides. Using MRI scans of the patient’s organs or bones, 3D models are created on which surgeons can experiment and virtually plan the operation ahead in detail, giving them an accurate idea of the depth and position of the incision. Surgical guides are used extensively in the fields of dentistry and orthopaedics, » and the solution saves precious time at over-subscribed surgeries. Another medical segment in which 3D printing has become indispensable is generic and custom implants such as hearing aids and hip replacements.

To keep up with growing demand in the field, and fight off mounting competition, 3D printing firms are hard at work to develop ever-more sophisticated products to meet the ongoing requirements of hospitals and laboratories. Prominent company Objet recently brought out a new printing material called The MED610, which combines bio-compatibility with high-dimensional stability and clear transparency, making it suitable for a wide range of medical and dental applications.

These precisely conceived characteristics assist in creating highly accurate, customised surgical guides. “Objet invests significantly in R&D in order to proactively meet the requirements of our customers. The advanced mechanical properties of the new Bio-Compatible material, including its clear transparency bring benefits to the entire medical and dental workflow – from surgical planning through to the procedure itself,” explained Avi Cohen, head of Medical Solutions at Objet, when the product hit the market during the latter part of 2011.

Designing your life

Far from being confined to practical undertakings, 3D printing can be used creatively as well, and the multi-tasking technology has cultivated a new breed of designers employing the processing method with gusto. For example, Bathsheba is a US∞based label carving a niche for itself with futuristic-looking mini sculptures and pendants printed in metal.

Showcasing the innovative prowess of the technology to the world of design, and demonstrating its boundless potential, 2011’s London Design Festival saw a project launch at the V&A Museum dedicated exclusively to 3D printing. Curated by New York-based gallerist Murray Moss and the Belgian industry mavericks behind additive manufacturing, Materialise, the exhibition presented a string of 3D works inspired by actual pieces from within the museum’s galleries.

Works that made the cut included the newly acquired Fractal.MGX table by Platform Studio and Mathias Bar. Conceived from a single piece of resin, the creation mirrors growth patterns occurring in nature. Significantly, the piece would be impossible to produce without 3D printing – a fact that no doubt impressed the professional design contingent. Another piece that formed part of the showcase was a 3D reproduction of a bust of Lady Belhaven, which dates back to 1827. The creative force behind the piece is notable milliner Stephen Jones, who, fittingly, adorned the fine Lady’s head with a quirky hat.

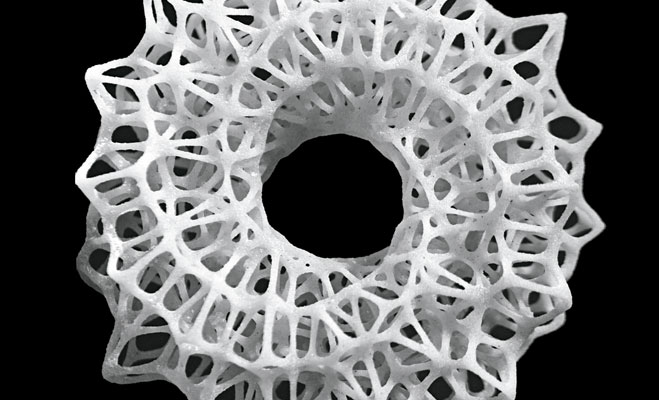

It might be a while before 3D printing enters the catwalk with aplomb, but already designers have started experimenting in the hope that the technology can assist in putting collections together. Skimpy garments are the most user-friendly alternatives, and swimwear lends itself perfectly to 3D printing, as pieces can be created in one sweep due to the limited amount of material required. Jumping on the 3D bandwagon, Continuum Fashion – which describes itself as: “part fashion label, part experimental lab” – teamed up with 3D print service Shapeways last year to create a piece of swimwear, the so-called ‘N12’ bikini. The print model of the garment emerged as a single piece, with no additional assembly required, and the material used was nylon 12, a solid plastic material that is designed to be so durable that it can be printed at a mere 0.7 mm.

Furthermore, the multi-tasking material offers waterproof properties and can be made into springs able to bend any which way. Combined, these qualities make for quite a handy material. “The bikini’s design fundamentally reflects the beautiful intricacy possible with 3D printing, as well as the technical challenges of creating a flexible surface out of the solid nylon,” says Mary Haung of Continuum Fashion. “Thousands of circular plates are connected by thin springs, creating a wholly new material that holds its form as well as being flexible. The layout of the circle pattern was achieved through custom∞written code that lays out the circles according to the curvature of the surface. In this method, the aesthetic design is completely derived from the structural design.”

Each N12 bikini is printed to order, and are available in an array of sizes. The potential of the concept within the fashion industry is potentially huge; however it may need a few more tweaks before it reaches the high street.

Carbon copies

Offering huge business potential, the 3D movement has given rise to a new industry within itself and many companies have sprung up in the past few years to hollow out a position for themselves before the market becomes saturated.

One of the most established companies within 3D circles is RepRap, short for ‘Replicating Rapid Prototyper’. The company was founded in the UK in 2005 by Dr Adrian Bowyer, a senior lecturer in mechanical engineering at the University of Bath. While the device allows for domestic generation of products, the ultimate goal of the project is to create a self-replicating device, which will ensure that the advance of 3D printing takes care of its own evolution and distribution. Already, the sophisticated machine is able to replicate a string of its own components.

MakerBot Industries is another notable firm offering accessible printers and associated products. One of its printers is called MakerBot Cupcake CNC. “I am an open, hackable robot for making nearly anything,” reads the company’s introduction to the device. In addition to printers, some other companies – Kraftwurx, Shapeways and Ponoko – offer online 3D printing services to consumers and industry folks alike. The service invites individuals and businesses to upload their own 3D designs. Once constructed, the products will then be shipped to the client.

Saviour of the world?

As 3D technology progresses, it presents a vast array of possibilities. Food can be replicated, as demonstrated by a team of researchers at Cornell University’s Computational Synthesis Lab. In 2010, the team made headlines with a 3D food printer that formed part of the so-called Fab@home project. “FabApps would allow you to tweak your food’s taste, texture and other properties,” team leader Dr Jeffrey Ian Lipton told the BBC while the device churned out what looked like liver pate canapés. Many scientists believe that if direct food replication is pursued, this form of 3D printing could help ease the burden on the world’s poorest and neediest.

Just as much as a breakthrough, it is believed that human organs might soon be created via 3D printing, too. Remarkably, US researchers at Cornell University announced last year that they had managed to engineer an ear made of silicone using a 3D contraption. As ludicrous it might sound to sceptics, hopes are high that they’ll be able to mastermind fully functioning human body parts in the future – an advancement that would solve the pressing problem of organ shortage that is plaguing the medical arena. Making that very possibility more viable, are another set of scientists – notably a husband and wife team serving at Washington State University – who have developed 3D printing techniques with the ability to create human organs, complete with blood vessels ready to be connected to the human recipient.

The creation of synthetic bones is also widely reported. Susmita Bose, who has acquired the figurative but somewhat derogatory nickname, “the bone printer”, has produced artificial bones since the late 1990s. When the innovation was originally brought to the attention of the media, she was subject of ridicule, but at the end of last year she received praise for having managed to grow actual bones around artificial scaffolds.

“We have tested it in small animal models and we have seen that bone grows over them very well,” Bose told The Atlantic Wire in December 2011. “We have also tested them with human bone cells and we’ve seen that bone will grow over them very well.” In an interview recently published by the BBC, Bose went on to paint an ever more promising picture for the future: “The way I envision it is that 10 to 20 years down the line, physicians and surgeons should be able to use these bone scaffolds along with some bone growth factors, whether it is for jaw bone fixation or spinal fusion fixation.” If Bose’s predictions become reality, a second industrial revolution is nigh.