Intelligent translators can’t grasp metaphor

Advanced translation technology may spell the end of the global language divide. However, one of the fundamental aspects of language could scupper such grand ideas

Though impressive, live translation can't deal with subtleties like metaphor

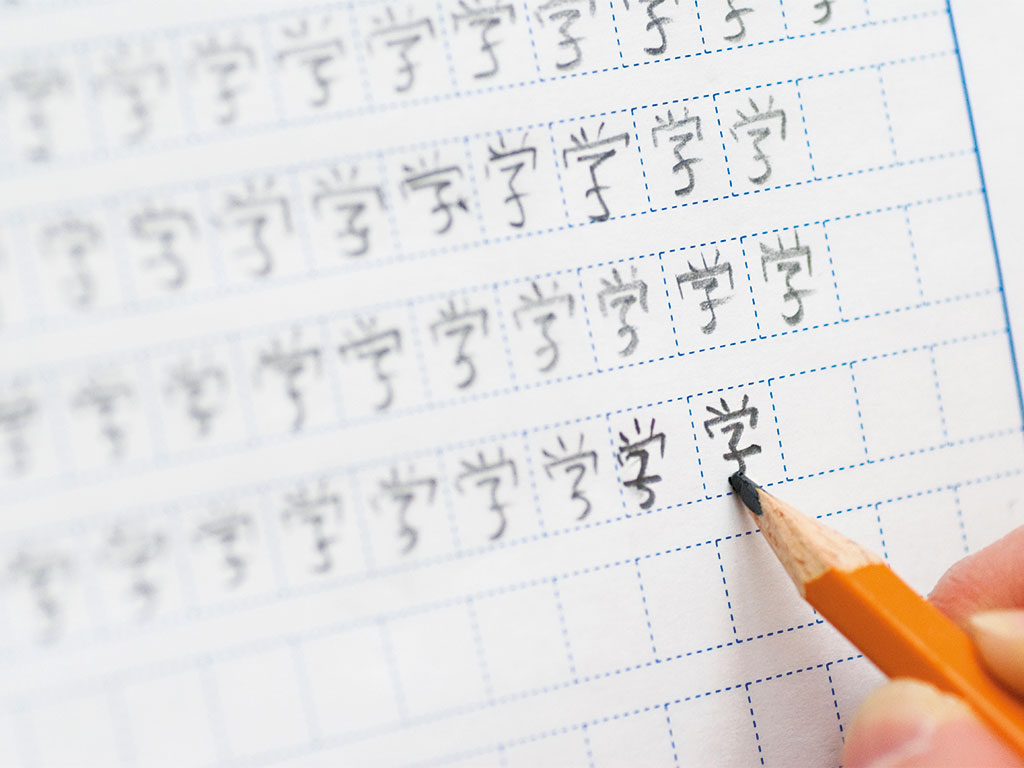

With the rise of China in the past few decades, many have speculated Mandarin will someday supplant English as the language of global business. For this reason, schools around the world are increasingly offering Mandarin lessons. However, mastering the language of China, in the hope of getting ahead in a world in which China is increasingly important, may be in vain – the language barrier itself may soon be broken down, owing to the rapid advance of computer translation technology.

Monolingual commitment

Alec Ross, author of The Industries of the Future and a former senior advisor for innovation to the US Secretary of State, has argued that, within 10 years, the global language barrier will be torn down. “A decade from now”, he wrote in The Wall Street Journal, “I would predict, everyone…will be able to converse in dozens of foreign languages, eliminating the very concept of a language barrier.” He continued: “A small earpiece will whisper what is being said to you in your native language nearly simultaneously as a foreign language is being spoken. The lag time will be the speed of sound.”

This would obviously provide untold benefits for businesses operating across national and linguistic borders. Awkward conversations in a convoluted version of the language in question would no longer take place, while finding a third-party translator to mediate conversations would cease to be an issue. A US businessperson could communicate clearly and instantly with a factory owner in Guangdong. Likewise, a meeting between the German, Brazilian and Japanese divisions of a global corporation could be carried out seamlessly, despite none of the participants speaking a common language.

Metaphorically speaking

However, this might be jumping the gun a little – such technology does not yet exist. Writing in The New Republic, David Arbesu, Assistant Professor of Spanish at the University of South Florida, pointed out that the nature of human language itself makes replacing human translators with machines particularly hard. Translation carried out by humans is not just “replacing a word with its equivalent in the target language”, he noted.

Language is largely metaphorical and figurative, and so the way “we speak often has nothing to do with the reality that surrounds us; machines are – and will continue to be – puzzled by the metaphorical nature of human communications”. One such example would be the common English-language phrase ‘seeing red’. That this alludes to anger – due to a cultural association between the emotion and the colour in some parts of the world – is not apparent in any literal sense. The phrase itself “has little to do with colours”, Arbesu pointed out, and therefore would not be clear to a computer. Likewise, merely replacing the English word for red with hóng – the Mandarin word – would not convey the intended meaning to a Mandarin listener.

In the groundbreaking book Metaphors We Live By, authors George Lakoff and Mark Johnson underlined the importance of metaphors with the example of comparing buildings to ideas: “Is that the foundation for your theory? The theory needs more support.” These phrases are metaphors, but we don’t often acknowledge them as such. An image of house foundations is not conjured up by reference to the foundations of a theory, yet its common use is precisely because we think and speak in metaphors where it is not obviously clear, even to ourselves.

Speaking in metaphorical ways is fundamental to how humans think and express themselves to other humans – but is not intelligible to machines. Until machines are made capable of interpreting both cultural context and abstract metaphors, cross-border collaboration in business will still need to rely on either human translators or people speaking a common language.