Cleaning up crypto’s dirty legacy

Bitcoin mining may have created a new class of crypto millionaires, but the industry’s vast energy usage and carbon footprint is having a detrimental effect on the planet

The energy needed to produce one bitcoin is also rising over time, due to a feature of the original software that only allows a single unit of the decentralised currency to be mined every 10 minutes

In Irkutsk, Eastern Siberia, the temperature barely creeps above freezing for at least seven months of the year. Life is hard for the city’s 600,000 residents – much of the local economy is based on energy revenues, meaning it was hit particularly hard by the 2014 oil crash. Suffering food shortages, unemployment and a bootleg alcohol tragedy that has killed at least 76, residents likely felt that there were few prospects left in this isolated, frozen wasteland.

In 2017, however, they found a glimmer of hope in an unlikely place: the nascent bitcoin market. The process of ‘mining’ for cryptocurrencies relies upon the one thing that Irkutsk has in spades – access to cheap energy. Bitcoin mining in particular is a hugely energy-intensive industry, as it requires multiple high-power servers working at full capacity to solve mathematical problems and generate currency. The technology also produces a huge amount of heat, so powerful cooling systems are vital – except in Irkutsk, where natural Arctic temperatures do the work for them.

The bitcoin industry has a huge carbon footprint, which could threaten any global progress made on tackling climate change

But while bitcoin mining may have boosted this struggling economy, it’s also causing significant environmental damage on a global level. The industry has a huge carbon footprint and produces a significant amount of electronic waste, which could threaten to derail any global progress made on tackling climate change.

Consumptive industry

Bitcoin, the decentralised currency system, was developed by Satoshi Nakamoto, the name given to the unknown individual or group that published the original open-source software in 2009. The value of each unit of the cryptocurrency has since risen exponentially, hitting a high of around $20,000 at the end of 2017.

To earn bitcoins, miners solve mathematical problems to verify ‘blocks’ that are stored in a blockchain ledger. “[Miners] are creating what we call ‘crypto hashes’ – they’re essentially trying out random numbers to try and find a signature for a new block,” explained Alex de Vries, a blockchain expert at PwC. Around two billion attempts are needed to identify this signature, hence why most miners have multiple computers working on problems simultaneously. This speeds up the process, but also increases the amount of energy used for each ‘mine’.

The energy needed to produce one bitcoin is also rising over time, due to a feature of the original software that only allows a single unit of the decentralised currency to be mined every 10 minutes. Due to the growing number of miners across the globe, each must solve an increasing number of problems per hour in the competition to score the bitcoin for that 10-minute period. “Every machine that’s added to the network takes a little bit of the same pie that everyone is eating,” said de Vries. More maths means more computers working, meaning more energy will be used. Mining computers have become more efficient, with the latest generation of machines able to create roughly 20 percent more crypto hashes per MWh of electricity. However, Alex Hern, Technology Editor at The Guardian, explained in a January 2018 article: “In the zero-sum game of bitcoin mining, that just means a miner can afford to run more machines at the same time, leaving their power usage roughly stable.”

Power needs

The sheer volume of energy needed means that areas such as Irkutsk are popular with bitcoin miners, as the Siberian Government only charges four cents per hour for electricity. For context, in New York City, energy costs 19.4 cents per hour. Part of the reason energy is so cheap in Irkutsk (and in other areas that are popular with bitcoin miners, such as China) is that it is produced by hydroelectric dams. This source of clean, renewable energy happens to be extremely inexpensive, as water is an abundant natural resource that is not affected by market volatility. Hydropower dams also require little maintenance, have low operating costs and produce a consistent and reliable source of energy for up to 100 years.

4¢

Cost per hour of electricity in Siberia

19.4¢

Cost per hour of electricity in New York

83%

of available bitcoins have already been mined

3.4m

Total bitcoins left to be mined

The use of hydroelectric energy to power the bitcoin mining industry has drawn criticism from environmental campaign groups for two reasons. First, cryptocurrency has no intrinsic value – its worth is entirely defined by market speculation. If the entire sector were to implode tomorrow, the most ‘successful’ miners would be left wringing their hands in dismay as they would have huge amounts of an immaterial product that had suddenly been rendered worthless. Cryptocurrency is also an adjunct industry, in that it is a carbon copy of the existing currency industry; it doesn’t solve any problems or fulfil any societal needs. As such, the use of one of the world’s cheapest clean energy sources to power this unnecessary and highly consumptive process is controversial, to say the least.

Second, the bitcoin mining industry demands constant access to power, which renewable sources don’t provide. As de Vries explained: “The sun isn’t always shining, the wind isn’t always blowing, and it’s the same for hydropower.” Therefore, in some areas, hydroelectric energy is supplemented by coal-based power, which is the most detrimental for the environment. “The presence of bitcoin miners could actually be a reason to either build new coal-based power plants or reopen existing ones,” de Vries told The New Economy. “That… happened in Australia last year, where a coal-based power plant was reopened for bitcoin mining. That’s the worst possible outcome of the process.”

An end in sight

Bitcoin’s vast energy needs have caused huge issues in countries with less-than-robust energy sectors. In Venezuela, according to cryptocurrency news website Bitcoinist.com, mining operations have caused widespread blackouts and have drained the national grid of electricity that could be used to power homes – particularly bad news for a country currently in the grip of the worst economic crisis in its history. According to estimates by the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, bitcoin consumes around 49TWh of energy per year – an amount that could power more than 4.5 million US households if it was redirected.

In addition to draining the world of energy, bitcoin is also causing significant environmental damage. The cryptocurrency’s current annual carbon footprint is roughly the same size as Singapore’s, according to data from Digiconomist. By effectively adding another country’s carbon impact to the global total, the world becomes increasingly unlikely to hit the warming targets set out under the Paris climate agreement. If these are not met, it will have disastrous consequences for weather patterns and ocean ecosystems.

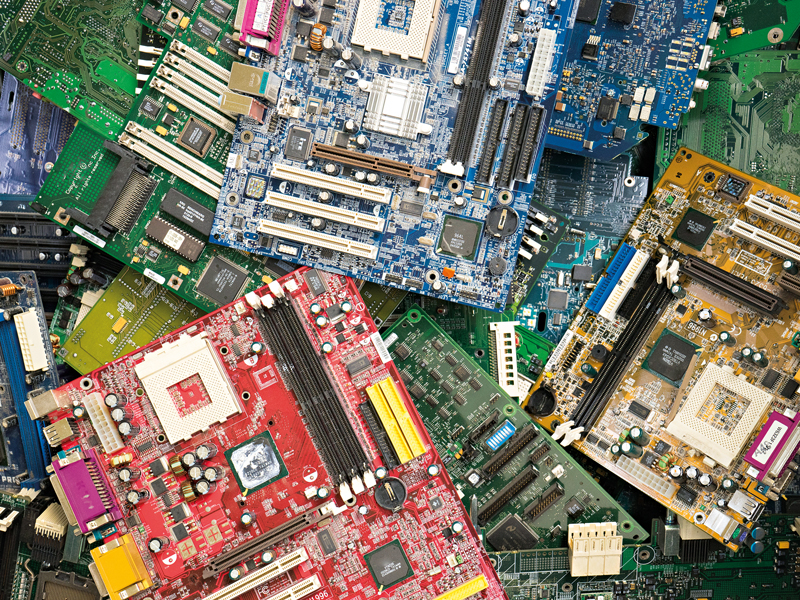

The industry creates a huge amount of electronic waste due to hardware burning out after a certain amount of time. “These machines cannot be repurposed, so they effectively become single-purpose, as they are hardwired for mining,” explained de Vries. “When they’re done, the only thing you can do with them is to throw them away – they become electronic waste immediately after they become unprofitable.” Just 20 percent of this waste is recycled globally, with the rest ending up in already-brimming landfills or incinerators.

‘The total electronic waste output of the bitcoin network is as much as Luxembourg, by my initial estimates, and that’s a very conservative number,” said de Vries. Add to that bitcoin’s massive energy consumption and carbon footprint and we’re looking at what can only be described as the planet’s worst environmental nightmare. Humanity is already decades behind in tackling our carbon impact – while we’re now taking some action on pollutants like fossil fuels, change simply isn’t happening fast enough. The last thing we need is another vastly consumptive industry adding to our substantial footprint.

There may be one slight silver lining, though, in the fact that there is a finite amount of bitcoins. Nakamoto only created 21 million coins in total, of which 83 percent have already been issued, meaning there are around 3.4 million left to be mined. Once all of those have been released, there’s a chance the industry may simply cease to exist. However, that’s little relief when you consider the damage bitcoin will cause to the environment between now and then. As de Vries concluded: “[The industry] could have a natural end, but then we’ve really wasted all this energy.”