The World Economic Forum faces big challenges at Davos 2020

The World Economic Forum Annual Meeting will return to Davos in 2020 to discuss the major issues facing the planet. If the showpiece event is to command the attention it craves, though, it will need to start finding some solutions to long-standing problems

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the 2017 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

The World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting seems to have lost its mojo – particularly in the West, where globalisation is being rejected in favour of a more protectionist outlook. What’s more, most observers of the 2019 meeting found that it fell a little flat. Headline speakers were underwhelming and failed to live up to the box-office acts of previous years, which included the likes of US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping. If future editions of the gathering are to prove their worth, they will need to consider the concerns of a world growing more antagonistic to the globetrotting elites who have become synonymous with the event.

Nevertheless, many of the chief talking points from previous years remain unresolved and are likely to dominate the agenda in 2020. Finding the right regulatory balance that can rein in the excesses of Silicon Valley’s tech giants without stifling innovation will undoubtedly be up for discussion once again. Trade tensions, meanwhile, don’t appear to be going anywhere and climate change looks as difficult to solve today as ever.

But the WEF’s yearly showpiece has never claimed to be able to single-handedly solve the major issues facing our planet. Instead, the gathering of business elites, experts and heads of state in Davos, Switzerland, simply aims to better understand and engage with these challenges. Each year, even if the forum only manages to spark one idea that makes the world a better place, surely it must be deemed a success.

In nobody’s best interest

In 2018, when Trump was in attendance at the WEF Annual Meeting, few would have predicted that the trade war wrangles between China and the US would still be plodding along today. Tariffs remain in place on billions of dollars’ worth of goods, forcing businesses in both countries to explore new markets, make cutbacks or simply shut up shop. In fact, the only thing that seems to be traded freely between the two superpowers these days is insults.

The International Monetary Fund’s latest estimates indicate that the US-China trade conflict has wiped as much as $455bn off the global economy – a figure that will surely continue to rise. It has reportedly already cost the technology industry $10bn and could end up setting back the average US household $460 a year, according to an analysis by London-based economists Kirill Borusyak and Xavier Jaravel. In China, meanwhile, the spat has contributed to an economic slowdown that has taken even the most pessimistic analysts by surprise. For the business leaders and government figures assembled at Davos, resolving the US-China dispute will no doubt be a priority.

Fortunately, the WEF has always been unashamedly pro-globalisation. Shortly after the Trump administration extended its tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, the WEF’s Aditi Verghese and Sean Doherty criticised the decision in an article entitled Trade Wars Won’t Fix Globalisation. Here’s Why. They wrote: “Short-sighted, protectionist measures ignore and erode the opportunities that [global value chains] provide for driving inclusive and sustainable growth and do nothing to optimise outcomes.”

But while some parts of the world wait to see what these two global superpowers will do next, others are keen to get on with things. In Africa, for example, countries are refusing to pull down the shutters and are instead opening themselves up to more international trade. Plans are afoot to launch the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a tariff-free continental market for goods and services that, according to the WEF, would instantly become the world’s largest trade bloc.

The AfCFTA will be implemented gradually, but it already has the support of 54 members of the African Union (AU), with the only exception being Eritrea. It’s hoped that the free trade area will boost intracontinental trade, which remains far below that found in other parts of the world: according to the African Export-Import Bank’s African Trade Report 2018, intracontinental trade in Africa sits at just 15 percent, far below the figures seen in Asia (58 percent) and Europe (67 percent). Preliminary estimates cited in the report suggest the establishment of the AfCFTA could see this figure rise to 52.3 percent by 2022.

“[The AfCFTA] will create jobs and contribute to technology transfer and the development of new skills; it will improve productive capacity and diversification; and it will increase African and foreign investment,” explained UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed at the formal launch of the AfCFTA. “Perhaps most important of all, the [AfCFTA] demonstrates the common will of African countries to work together to achieve the vision of the [AU’s] Agenda 2063: the Africa We Want. It is a tool to unleash African innovation, drive growth, transform African economies and contribute to a prosperous, stable and peaceful African continent, as foreseen in both Agenda 2063 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

At the WEF on Africa event held in August, there was much discussion as to why Africa is choosing to integrate its economies at a time when other parts of the world are adopting a more isolationist approach. Crucially, the leaders of the AU are already discussing ways to ensure that the continent’s less developed economies – and, indeed, its poorest citizens – are not negatively affected by a more liberal approach to trade. It’s a topic that will undoubtedly be returned to in Davos at the turn of the year.

Worlds apart

Silicon Valley’s technology giants had their toughest year for a long time in 2018: Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg faced a grilling from US Congress; Google saw several employee walkouts over the firm’s inadequate response to sexual harassment claims; and Apple had to navigate reports that some of its products were susceptible to Spectre and Meltdown security vulnerabilities. Scrutiny of said tech firms continued into 2019, albeit not to the same degree. In June, Facebook decided that its dominance of the social media space was not enough and began eyeing the financial services market. Its unveiling of a new digital currency called Libra, however, was met with a less-than-enthusiastic response.

Reactions to Libra have ranged from the indifferent to the indignant. Some predict the currency will have little impact when it launches in 2020, with detractors (such as The Week’s Jeff Spross) suggesting that it offers few points of difference from existing mobile payment apps. For others, the currency poses a threat to the monetary sovereignty of nation states. That’s certainly the view of the French Government, which has moved to block the development of Libra in Europe.

Regardless of whether Libra goes on to change the world or not, the conflict between Facebook and France touches upon a broader challenge presented by today’s rapidly advancing digital economy: how to legislate on new developments in a way that protects citizens without stifling innovation. In addition to Silicon Valley’s heavy hitters, a number of entrepreneurs and pioneering start-ups are busy trying to create the next big thing in areas like self-driving vehicles, the Internet of Things and quantum computing. It is becoming increasingly clear that regulators will need to grapple with these developments sooner rather than later.

Deciding just how obtrusive regulations should be is becoming more difficult. Not only is technology advancing rapidly, it is developing all over the world and in different regulatory climates. US institutions may determine that AI needs another decade of research before it can be employed in, say, the medical field, but if China thinks such delays are unnecessary, the US risks falling behind. In today’s winner-takes-all economy, coming second is the same as not being in the race at all.

Already, China’s less stringent regulatory approach is paying off. The country has quickly become a world leader in genome editing, overtaking the likes of Japan and the US, where obtaining government approval for human trials is more difficult. Similarly, China is making impressive strides in terms of AI development. To function effectively, the technology requires reams of data that will allow it to ‘learn’ the correct way of acting, whether that concerns autonomous vehicles, natural language processing or facial recognition. China, which has a very different attitude to online privacy than countries found in the West, has an advantage here, too.

“Organisations should work on a responsible privacy programme,” Paul Breitbarth, Director of EU Operations and Strategy at Nymity, told The New Economy. “That means looking at which requirements for privacy and data protection apply to you, in all the jurisdictions where you operate, and to implement policies and procedures to deal with them.”

In China, however, a responsible privacy programme places national interests above individual ones. According to a national intelligence law introduced in 2017, organisations must support and cooperate with government authorities when they request information that relates to national security issues. Critics believe the wording of the law is vague enough to permit widespread state surveillance. Businesses all over the world may be trying to win the tech race, but they are not all playing by the same rules.

Still, companies headquartered in Europe and the US should be wary of pushing regulators to place technological progress ahead of ethical considerations. Instead, markets need to clearly state that they will not use Chinese technology – regardless of how cheap or effective it is – if it has been developed using morally dubious means. That would send a clear message, while also giving firms a financial incentive to adopt sound principles.

If this approach works, then perhaps the future could see western and Chinese firms collaborating on new technology. This may seem unlikely at present, but this is the sort of long-term ambition that those present at Davos should be striving for – integrating China more closely with the global community.

A hot mess

As is the case every year, those gathered at the WEF Annual Meeting (many of whom arrive by private jet) will be set the unenviable task of trying to win the fight against global warming. While it is easy to sneer at the jet-set elite for not practising what they preach, finger-pointing will achieve little – the time for action is already long overdue.

Throughout 2019, a number of natural disasters provided a reminder of just how urgent the situation has become. In September, Hurricane Dorian became the strongest storm to ever hit the Bahamas, resulting in billions of dollars’ worth of damage and leaving at least 61 dead. While rising global temperatures do not cause storms like Dorian, they can boost their intensity. For the strongest storms, climate scientists have found that the sustained wind speed increases by approximately eight percent for every one degree Celsius of warming. The surface sea temperatures measured in the area where Dorian formed were higher than usual (especially when compared with pre-industrial levels), but such figures – and the disasters they engender – are likely to become the new normal if humans fail to cut their carbon emissions drastically and without delay.

Although the Paris climate accord has been criticised for its ineffectiveness, all hope is not lost. Greta Thunberg, a speaker at last year’s WEF Annual Meeting, continues to galvanise her supporters by preaching the importance of sustainability. It’s a message that national governments have increasingly been espousing themselves. In both the US and Europe, environmental policies are now firmly part of the political conversation: for instance, new European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has made the European Green Deal a central part of her plans in office, which also include making Europe the world’s first carbon-neutral continent by 2050.

“We must go further, we must strive for more,” von der Leyen said in a speech during her candidacy for the commission presidency. “A two-step approach is needed to reduce CO2 emissions by 2030 by 50 – if not 55 – percent. The EU will lead international negotiations to increase the level of ambition of other major economies by 2021. Because to achieve real impact, we do not only have to be ambitious at home – we have to do that, yes – but the world has to move together.”

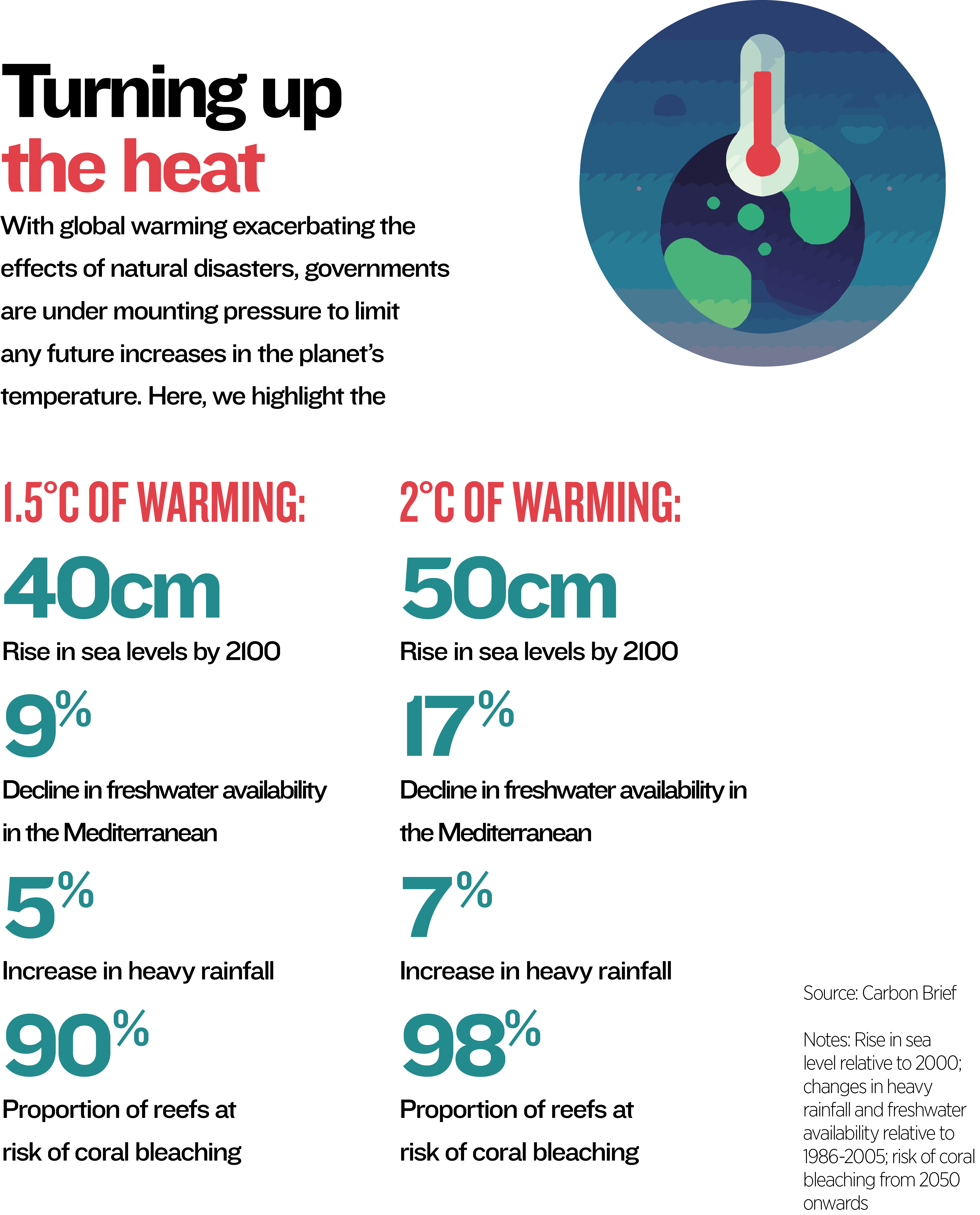

On the other side of the Atlantic, figures on the political left, such as US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are pushing their own version of the European Green Deal that would reshape the US economy. The Green New Deal, as it is known, promises to decarbonise the manufacturing and agriculture industries, build a national energy-efficient smart grid and turn green technology into a major US export. These proposals are ambitious, but that’s because they have to be – according to the Carbon Brief website, even if the global temperature is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, sea levels will rise some 40cm by 2100, freshwater availability in the Mediterranean will fall by nine percent and the intensity of heavy rainfall will go up by five percent. If temperatures increase to a greater extent, the outcomes are even worse.

Despite the efforts of politicians around the world, the most pessimistic estimates indicate that it will not be possible to reduce the planet’s CO2 emissions quickly enough to avoid catastrophe. Instead, states may need to deploy less conventional solutions to meet their environmental goals. One potential option would be to invest more heavily in carbon capture and storage technology. This can be used to greatly reduce the CO2 emissions produced by the burning of fossil fuels and, when combined with renewable biomass, can even lead to carbon-negative energy. Similarly, several organisations have developed methods to remove CO2 from ambient air using an absorption-desorption process.

It is depressing that humanity has treated the planet in such a way that simply reducing fossil fuel usage is unlikely to be enough to sidestep disaster. At this year’s WEF Annual Meeting, talks will once again focus on efforts to cut down global greenhouse gas emissions. Ultimately, though, new technology may have to come to the rescue.

Fresh thinking

Making things more difficult is the fact that these challenges must be tackled at a time when political and economic stability is far from guaranteed. More than 10 years have passed since the global financial crisis, but the world economy is still suffering a hangover. “Current economic momentum remains weak, while heightened debt levels and subdued investment growth in developing economies are holding countries back from achieving their potential,” World Bank Group President David Malpass said in June. “It’s urgent that countries make significant structural reforms that improve the business climate and attract investment. They also need to make debt management and transparency a high priority so that new debt adds to growth and investment.”

The eurozone, for example, is expected to grow by just 1.4 percent across 2020, while US-China trade tensions threaten to dampen business and investor confidence in both markets for the foreseeable future. Political change may provide a path away from this stagnation: the US presidential election is scheduled for late 2020, while the EU has recently appointed new heads of the European Commission and European Central Bank. However, as we are all well aware, politics is always rife with uncertainty. Change can be both positive and negative.

Attendees at the 2020 WEF Annual Meeting will be hopeful that fresh leadership can set the planet on a course for closer economic collaboration, stronger financial stability and longer-term environmental sustainability. If discussions at Davos can help in any of those areas – even in some small way – then perhaps the event can recapture some of its lost spark.