The changing face of mining sector investment

With multiple write-downs and restricted funding conditions, traditional investors are shying away from the metal mining market

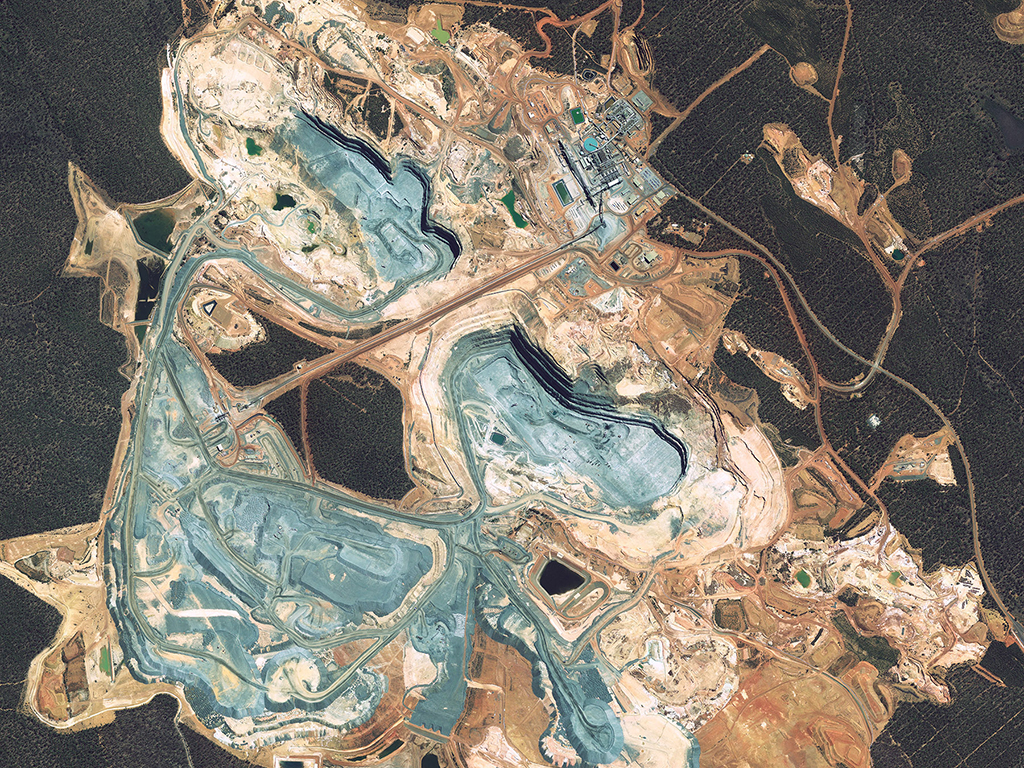

Australia’s Boddington gold mine. The gold industry is advised to be more consistent with its published figures

A recent report on mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in the mining industry shows there is to be a significant rise in activity from non-traditional investors in 2013. The sharp increase in deals is expected to come from private capital, state-owned enterprises (SOE) and sovereign wealth funds (SWF). These state-backed and private financial groups have shown a steady growth in interest and were responsible for 31 percent of the deals made in 2012: up from 21 percent in 2011.

Traditional investors, who have been responsible for the majority of M&A deals since 2009, have become less willing to invest and the value of transactions reached a five-year low of $2.9bn in 2012. They have been inclined to take smaller, non-controlling stakes in companies and are interested in shorter return timeframes.

Mike Elliot, Global Mining and Metals Leader at Ernst & Young, said: “The funding gap is being filled by private investors and SOEs, who may not be dislodged from their newfound positions once the cautionary investment environment recedes and traditional investors return to the sector.”

A new deal

The restricted funding conditions mean smaller mining companies with development assets will be more inclined to carry out deals with new investor groups in order to finance project construction. Paul Murphy is Australia and Asia-Pacific Mining and Metals Transactions Leader for Ernst & Young, publishers of the report. He said: “They have not got much of a choice right now. Either they raise equity and get diluted, they merge, or they get taken out.”

SOEs are expected to be the biggest of the new wave of backers in 2013, with China the dominant force, driving long-term aspirations to feed the growing demand for metals in its domestic market. China’s main activity has been in Africa, which makes up 75 percent of its foreign mining investment.

In 2012, China was the largest acquirer of African frontier markets and accounted for two-thirds of the growth in demand for steel and aluminium worldwide: as well as being the biggest importer of iron ore and coal, according to research by Bloomberg. It is active in other mining markets and, in February, China’s largest state-owned investment company, Citic Group, paid about $452m for a 13 percent stake in Australia’s Alumina Ltd mining company.

Richard Tory, Head of Natural Resources for Morgan Stanley’s Asia-Pacific region, said: “With stronger and bigger Chinese players emerging, we could see a significant pickup in the volume of overseas acquisitions.” SWFs, particularly those from the Middle East, are also investing heavily in African mining, with the aim of diversifying their portfolios and becoming less reliant on oil and gas revenue. They have been welcomed into Zimbabwe by the Movement for Democracy group, which hopes the activity will help generate capital that can then be redistributed among the population.

The government in Western Australia launched an SWF last year to take long-term benefits from the boom currently provided by the mines in the area. The fund was paid for from $1.1bn of government mining royalties. West Australian Treasurer Christian Porter said he hoped the fund would be worth $4.7bn by 2032.

Interest grows

It is predicted there will be continued growth in interest from non-traditional private capital and hedge funds in 2013. Unlike other new investors, they are putting venture capital into junior mining companies in order to secure small, non-controlling stakes. They hope to profit from commodity prices, which they believe will improve alongside the global economy. According to Ernst & Young, 80 percent of the deals made by private capital and hedge funds in 2012 were for non-controlling interests.

The volatility of commodity prices led to a depression in miners’ share value

Bloomberg Industries’ Global Head of Metals and Mining Research, Ken Hoffman, spoke about the different attitude new private investors are bringing. He said: “Private-equity funds have a completely different outlook on the mining industry from traditional investors. The most important thing for a private-equity fund is locking in guaranteed cash flow from its investment… this means they may look to acquire strategic stakes in companies hedging output… in 2013 and beyond, you could see a complete transformation of this industry into something that is a product produced for cash flow.”

David Baker, Managing Partner at Baker Steel, believes mining companies have to shoulder some of the blame for the drop in interest from more established backers in 2012. Using the gold industry as an example, he believes businesses are confusing investors by publishing reserve and production figures in gold and then benchmarking against the greenback, which has been depreciating.

Baker said: “Mining companies need to restore trust and give more clarity… we believe the mining companies should be consistent and report in gold. This would then give investors a clearer picture on how much gold it is costing to mine the resource and how many ounces of gold are added to the shareholder vault.”

Losing value

The downturn in majority takeovers has been felt heavily by the industry, leading Bloomberg to speculate that they are paying the price for the surge in interest over the past decade at $1.1trn. About $50bn has been wiped off the value of projects at the biggest mining companies in the last year. Rio Tinto announced it is taking a $14bn impairment charge, $3bn of which came from its failed coal-mining project in Mozambique, nearly wiping out the $3.7bn it paid in 2011.

A spokesperson for the company said: “In Mozambique, the development of infrastructure to support the coal assets is more challenging than Rio Tinto originally anticipated.” The remainder of the write-down is from its $38bn acquisition of Alcan in 2007. The group’s CEO, Tom Albanese, bore the responsibility and has been forced to step down.

Elsewhere, Barrick Gold has said it is taking a $4.2bn write-down on the $7.3bn it paid for the Lumwana Copper mine in Zambia. Evy Hambro, Manager of BlackRock’s World Mining Fund, said: “Companies are now starting to come clean with many of the mistakes they’ve made over the last few years… It wouldn’t surprise me to see more write-downs.”

A number of CEOs have shared the same faith as Albanese in the early months of 2013. Cynthia Carroll gave in to criticism from the shareholders at Anglo American in relation to cost overruns that led to a $4bn impairment charge at the companyís flagship iron ore drilling programme in Brazil.

Marius Kloppers of BHP Billiton stepped down after the company reported a fall of 58 percent in half-year profits. BHP firmly blamed “substantially lower” commodity prices and rising operational costs for the slump. Ernst & Young’s Director of Transaction Advisory Services, Michael Bosman, compounded this idea. He said: “[The] value of financing, raised last year, fell as traditional investors reduced their exposure due to softer commodity prices.”

Many believe the volatility of commodity prices led to a depression in miners’ share value, in turn causing many risk-averse buyers to offer less. The report says: “Sellers were unwilling to accept lower valuations based on their depleted share prices in 2012, on the grounds that this unfairly reected near-term uncertainties, rather than the long-term potential of their assets. Consequently, negotiations are taking longer and becoming more complex, resulting in sluggish M&A at best.”

Investments from non-traditional parties are expected to re-ignite interest from the more traditional groups in the coming year. According to Ernst & Young’s report: “In the longer term, further investment is likely to follow from traditional investors as the impact on the region’s infrastructure from the investments made by Chinese SOEs and sovereign wealth funds filters through, translating into future

M&A opportunities.”