World Bank: economic growth “not enough” to end poverty

New World Bank paper highlights the challenges of identifying those who have been reduced to extreme poverty

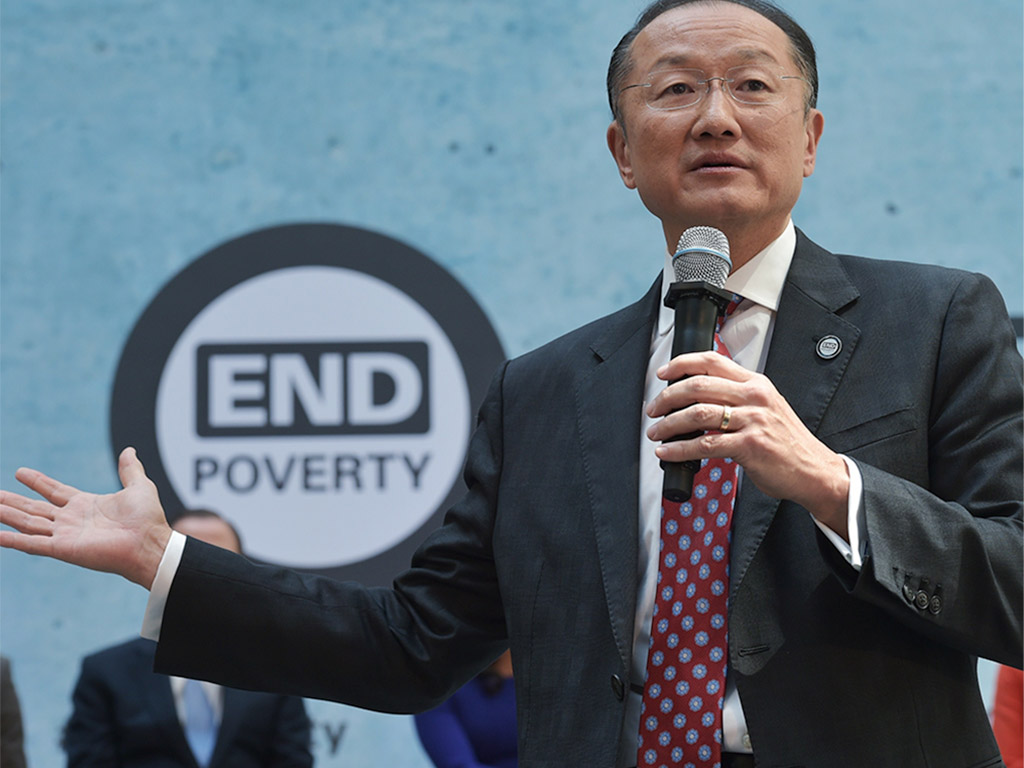

World Bank President Jim Yong Kim spoke of the need to end poverty by 2030 at an event at the World Bank Headquarters in Washington, emphasising that economic growth is not enough to reduce it

A new paper published by the World Bank states that bringing an end to extreme poverty requires far more than economic growth, and calls for greater inclusiveness in eradicating the issue before 2030.

“Economic growth has been vital for reducing extreme poverty and improving the lives of many poor people,” said the World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim. “Yet, even if all countries grow at the same rates as over the past 20 years, and if the income distribution remains unchanged, world poverty will only fall by 10 percent by 2030, from 17.7 percent in 2010. This is simply not enough, and we need a laser like focus on making growth more inclusive and targeting more programs to assist the poor directly if we’re going to end extreme poverty.”

The bank last year set 2030 as the predicted year in which extreme poverty would be brought to an end, though the institution’s newest findings have since made the target look rather too ambitious. In place of focusing solely on economic growth, the World Bank believes that ending extreme poverty calls for more effective channels of distributing wealth, whether this be through more inclusive mechanisms or government programmes.

[T]he World Bank believes that ending extreme poverty calls for more effective channels of distributing wealth

“It is a sad commentary on our prosperous world that over one billion people live in extreme poverty,” said Kaushik Basu, Senior Vice President and Chief Economist at the World Bank. “It is a welcome call from the World Bank Group to not just mitigate poverty but bring it to closure and also to strive for a more equitable world. To achieve these ends we will need determination, but also ideas and innovation, for the ways of the economy can be strange.”

One of the key challenges in tackling extreme poverty, says the institution, is in recognising the bottom 40 percent of any one single country and understanding the ways in which the population differs from place-to-place. For example, whereas in Rwanda 63 percent live in extreme poverty, as little as eight percent suffer the same fate in Colombia. By pinning down the actual extent of poverty in each country, the bank can then craft country-specific policies to more effectively address the issues at hand.

Regardless, the bank has long been criticised for being too slow to change its methods, and the organisation’s propensity for large-scale infrastructure projects means that poor countries are now being forced to borrow excessive sums of money to fund the changes.