Tinder and other apps struggle to monetise their offerings

For all the apps swirling around the web, very few have worked out the best way to make money. Jules Gray looks up from his phone to ask why

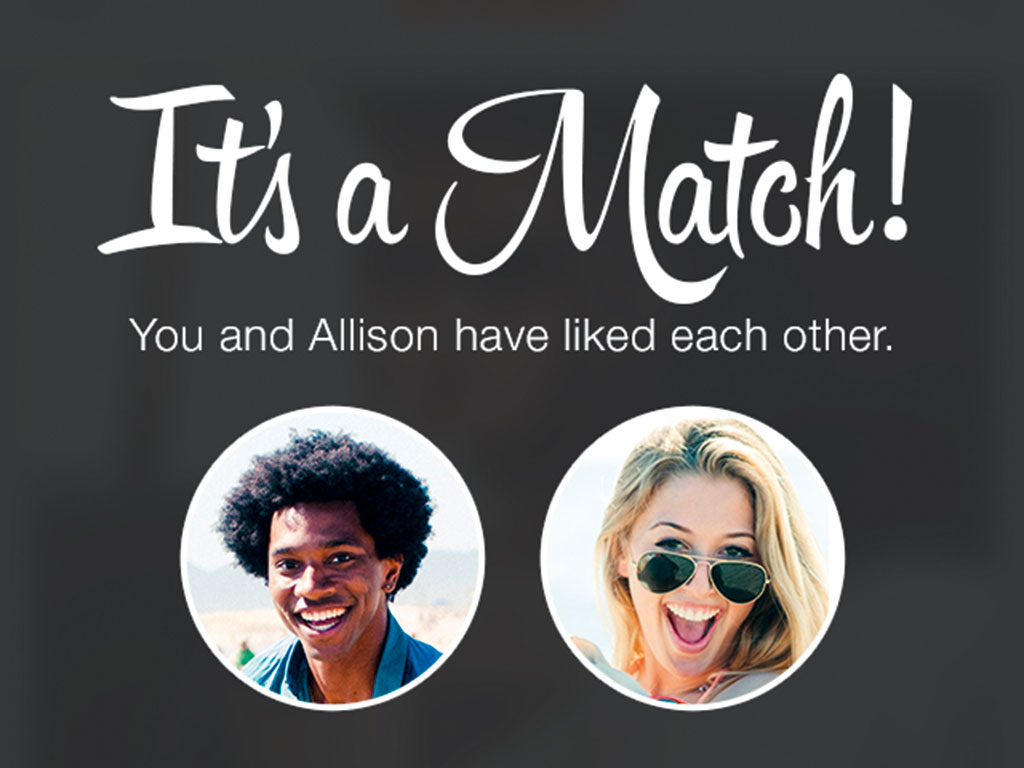

Despite experiencing a phenomenal growth in popularity since launching in 2012, Tinder has struggled to monetise its offering. Only recently has the company announced plans to launch a paid-for service with additional features

Just seven years ago, had you asked someone how many apps they had, they’d most likely have looked at you blankly and accused you of being a colossal nerd. Now the term has become part of everyday language, with people owning smartphones that house hundreds of the things. These ‘things’ (i.e. mobile applications) have transformed the way in which people interact with their phones, and revolutionised the world of software development.

Smartphone platforms have opened up a world of opportunity for software developers, with individuals, small start-up companies, and major designers all clamouring to get in on the action. However, opinion is split on how to actually make money from mobile apps. While some favour one-off payments for their work, others employ a range of different methods, such as advertising or a ‘freemium’ service (where the initial app is free but upgrades or additional services must be paid for).

Direct sales of apps can prove attractive to companies looking to see a guaranteed return from every copy downloaded. It is a popular method for apps that aren’t going to continually offer new features and often require a higher initial cost. These include popular games such as Angry Birds. However, for all those offered on Apple’s iOS platform – the biggest revenue generating system on the market – Apple takes a 30 percent cut.

30%

Apple’s cut from each iStore app sale

Other developers choose to offer sponsorship around their apps. Time Out magazine’s app has done this with vodka maker Smirnoff, while The Economist entered into a similar deal with Lloyds Bank. This is particularly attractive as the sponsors’ logos don’t impact on the user experience (a problem many people have with ad-based apps).

Annoying pop-up adverts that have to be watched or closed before an app’s content can be accessed may bring in money to the developer, but they detract from the user’s enjoyment. Twitter is yet to work out a way in which it can generate revenues that match its vast user base: attempts to insert discreet promotional tweets into people’s timelines have received furious responses from many users.

Other firms (such as music-streaming firm Spotify) offer two versions of their apps: a free, lighter version that comes without many features and is littered with adverts; and an ad-free, paid-for version with a full range of features.

Finding the money

The way in which app designers try to monetise their work depends on the type of service being offered, but also on the current trend. Initially, advertising was a popular method, but soon proved unpopular with users who became frustrated with the amount of garish pop-up marketing that got in the way of the app they were trying to use. The next trend was the freemium model, but this has turned out to be hugely controversial: countless stories have emerged of children making in-app purchases on games their parents had presumed were free, racking up huge bills. Currently, there doesn’t seem to be a consensus on how best to monetise mobile apps, but a few of the biggest developers are coming up with new models.

News emerged in October that mobile dating app Tinder would soon start to offer a premium service. Tinder has become hugely popular since its launch in 2012, in part, presumably, because it has been free to use. As a result, however, it has not been able to generate much in the way of revenue. Now the service is beginning to look at ways it can turn all that activity into money.

Having initially toyed with the idea of adding advertising to the app, Tinder has instead gone for the freemium model. Sean Rad, Tinder’s CEO, told tech website the Drum: “We are adding features users have been begging us for. They will offer so much value we think users are willing to pay for them. We had to get our product and growth right first. Revenue has always been on the road map.”

Another firm to take a different approach is messaging service WhatsApp. The service was initially free when it launched back in 2009, but quickly adopted a paid model so it could handle the surge in users. By mid-2013 – six months before Facebook paid an astonishing $19bn for it – the company implemented an annual subscription fee. For $0.99, users are now able to message their friends to their hearts’ content.

Trial and error

In September, Tim Rea, the CEO of global messaging app Palringo, told technology website TechRadar: “It goes without saying that the service needs to be good quality and engaging. I use the word ‘service’ rather than ‘app’ because in many cases I think it is dangerous to think and talk about ‘an app’ as though it is a one-off piece of development that a developer throws out there. A service is different.”

Palringo now employs a free service with in-app purchases, but the core use of the app remains free for users. Getting to this point took a while, says Rea: “We went through various stages starting, with a naive view that we’d have a cool messaging app, generate some ad dollars and then charge people for some element of usage. We then went through a phase of thinking maybe we shouldn’t worry about getting money from consumers, but instead try to deliver parallel services to telecoms (white label) and to enterprise and just charge them, maybe justifying the consumer service on the basis that it is a great test bed. Then, a little over a couple of years ago, we took a cold, hard look at the situation and decided that we needed to focus down onto a particular niche and build a suitable, sustainable model that we could then expand up into a viable business.”

Offering incentives to users to pay for additional content is the model Rea believes works best: “It focuses attention on what users are doing, what they are interested in and what they want. It generates some money versus free-to-use apps and is a basis for a real business versus ad-based approach.

“As I said, an ad-based approach can be viable but it’s tricky. Generally in the mobile world it just doesn’t work well because we have got into a view of the world that has most publishers thinking ‘if my users don’t pay I will show them ads’ so they are basically saying: ‘Hey, I’ve got a bunch of people who I know will not pay and I’ll show them your ads!’ That is why they are not worth much. Beyond that, a service needs decent, coherent volumes of users and an ability to properly characterise their audience and package them for sale. Not so easy.”

Which method app-makers choose ultimately depends on the type of service they are offering. Controversies over micropayments and annoyance with intrusive advertising will likely mean new services will have to go down the same route as Tinder and offer a free service in order to capture users. The question is what to do when those users are secured, and how to avoid alienating them while also taking their money.