Amid the constant wrangling over making sure member states meet supposedly strict EU emissions targets, governments have tended to favour domestic policies over wider initiatives. While there have been calls to make governments collaborate in order to meet these targets, many administrations in Europe have backed domestic energy providers, rather than allow sharing of power across border.

Creating greater efficiencies between countries in how energy is generated and shared is an integral part of building a more sustainable world. In Europe, it would also greatly increase energy independence at a time when many EU countries are heavily reliant on Russian and Saudi Arabian oil and gas.

It is widely agreed that renewable energy is the future of the energy industry. Even those at the top of the oil industry will admit that, with fossil fuels depleting, the world will need to rely increasingly on renewable sources that are both sustainable and cheaper. However, although policymakers the world over have talked tough about the need for countries to sign up to strict targets on renewable energy, the reality has been quite different. Countries have done their level best to scale back renewable energy subsidies in the face of economic trouble and a raft of new fossil fuel discoveries (which are partly due to the proliferation of shale drilling). While the renewable energy industry has certainly been harmed by this trend, its importance as a long-term solution to the world’s energy troubles remains.

40%

Target reduction in EU emissions by 2030

€40bn

Potential savings from a common EU energy market

350 miles

Total Length of the NorGer cable

€2bn

Cost of HVDC Norway-Great Britain

€2.5bn

Potential cost of the UK-Spain link

Blocking progress

With many domestic industries reliant on one form of power, it is hard to force countries to buy their neighbours’ energy. This recently became apparent in the EU with a report that Spain and Portugal were having difficulty selling their abundant supplies of wind-generated power to neighbour France, which has invested heavily in its own nuclear power industry.

Spain currently produces far more energy through its wind turbines than it needs. However, for decades, the French have blocked proposals to build interconnectors across the Pyrenees: they claim such cables would be too expensive to build through the rock, and that they would harm the natural beauty of the mountain range if they were built overhead. However, many believe the true motivation of successive French governments has been the protection of their country’s domestic nuclear energy industry.

It is the importing of energy from abroad, however, that is Europe’s biggest problem. With Germany so heavily reliant on Russian oil and gas, it has found it very difficult to sign up to tough sanctions on Moscow after recent political troubles in Ukraine. Terrified of being pushed back into a recession if Russia turns off the power, Germany has tried to play the mediator in the dispute between Ukraine, NATO and Russia.

Poland’s Prime Minister Donald Tusk proposed one solution to this problem last April. A European energy union, he said, would cut the EU’s reliance on foreign power, while also creating greater efficiencies in how energy is used. This would in turn help countries meet their energy targets, which state greenhouse gas emissions must be cut by 40 percent by 2030.

Tusk’s plan would bring huge benefits to the EU, with consultancy group Strategy& predicting as much as €40bn could be saved each year as a result of such a strategic energy policy. It would considerably cut the EU’s reliance on Russian imports at a time when Moscow is meddling in the affairs of some of its eastern members. It would also greatly improve cross-border infrastructure, while standardising EU-wide energy prices for consumers.

Tusk said that, while the plan may seem like a fantasy, it must be implemented if the EU is to avoid the sort of troubles it experienced during the financial crisis. “The banking union also seemed close to impossible, but the financial crisis dragged on precisely because of such lack of faith,” he said. “The longer we delay, the higher the costs become.”

Infrastructure changes

EU policymakers believe one of the preconditions of energy trading within an integrated energy market is the availability of the necessary infrastructure. This means that, for renewable energy to be traded, there need to be interconnected grids between EU member states. The European Commission and Energy Union Vice-President, Maroš Šefčovič, is actively encouraging France to upgrade its electricity interconnection

capacity as a result.

Šefčovič believes France’s limited grid capacity with neighbouring countries such as Spain continues to inhibit the development of competition and constrains the security of supply. It’s also been argued France would benefit from the further liberalisation of its wholesale electricity markets, which is currently one of the most concentrated in the EU.

The EU is aiming to achieve a minimum target of 10 percent of existing electricity interconnections by 2020 for member states that have not yet reached a minimum level of integration in the internal energy market. This means countries such as Spain, which are relatively cut off from the rest of Europe’s energy grid, need to be allowed to connect through their main point of access to the internal energy market: in the case of Spain, that means France.

In order to encourage France to open its grid up to countries such as Spain, the European Commission has a number of priority schemes, dubbed ‘Projects of Common Interest’, which are eligible for EU funding. This will help France increase interconnection levels with the UK, Ireland, Belgium, Italy and Spain, while removing bottlenecks and integrating renewable energy into the network.

Šefčovič says: ”We need to have adequate energy infrastructure with good interconnections, in particular to integrate renewables into the grid and to unlock energy islands. Structural funds, the Connecting Europe Facility, joint investments and the future Juncker Investment Package can contribute to the financing of these energy infrastructure projects and modernise the EU’s energy system.”

Whether France will be willing to allow an influx of cheap renewable energy onto its grid, and therefore reduce the country’s reliance on nuclear power, remains to be seen. However, for the EU to be a successful in its mission to create a common market for energy and reduced emissions, France should be encouraged to open up. If it is unwilling, it should be forced.

Progress in the north

While France might be reticent to allow other countries to sell their power onto its grid, many within Europe and nearby are more amenable. Norway has been particularly active in connecting its energy output to the rest of Europe in the south, even though it is not a member of the European Union. As an integral member of the European Free Trade Association, however, it enjoys strong ties with its southern European neighbours.

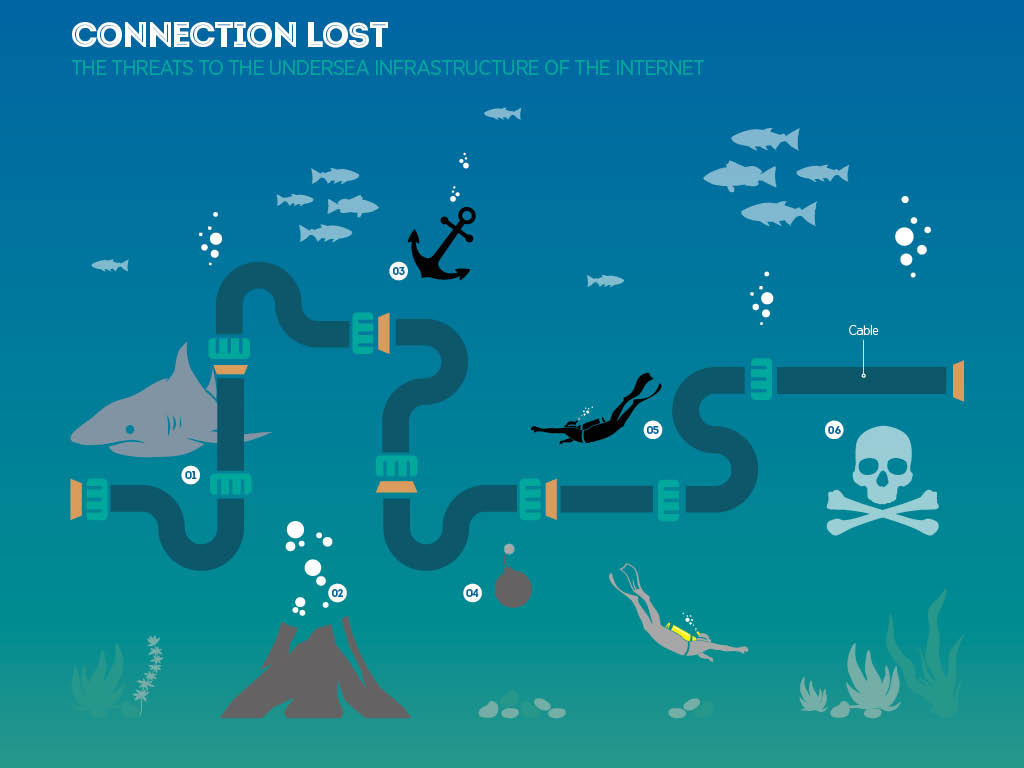

Much of Norway’s generated power is being exported to its neighbours through the creation of a series of underwater interconnector cables. One project, dubbed ‘NordLink’, will provide a 1,400MW link between Norway and Germany, at a cost of nearly €2bn. Half of the project is owned by Norwegian operator Statnett SF, while the remainder is split between German operator TenneT TSO and Germany’s state-owned KfW.

NordLink is not the only interconnector project being built between the two countries. NorGer is another 1,400MW cable that will pass through the North Sea and run for 350 miles. It will transfer electricity generated by Germany’s wind power industry, while hydroelectric power from Norwegian reservoirs will travel in the other direction.

The UK and Norway are building a €2bn high-voltage direct current electricity cable under the North Sea, from Blyth in England to Hylen in Norway. Known as the HVDC Norway-Great Britain, it was first proposed in 2003 by Norway’s Statnett and the UK’s National Grid. The scheme was intended to be a 1,200MW interconnector, but the project has since grown to a 1,400MW cable that will run 442 miles: the longest underwater cable in the world. Set to be completed in 2020, the line will connect the two countries’ electricity, but could also them to connect the North Sea wind farms and offshore oil and gas platforms.

Another joint project between the UK and Norway is the Scotland-Norway interconnector known as NorthConnect. The £1.75bn project is also hoped to be completed by 2020, and will see a 350 mile HVDC cable run under the North Sea between Peterhead in Aberdeenshire and Samnanger in Norway.

Baltic connections

The Baltic states have also unveiled plans to build an extensive network of energy interconnections, known as the Baltic Energy Market Interconnection Plan (BEMIP). The countries taking part form the Member States of the Baltic Sea Region (Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Denmark and Sweden), as well as Norway, which will observe the plan. The plan includes a range of energy proposals that will tie up the region’s electricity, nuclear power and gas.

In a progress report released in 2011, the EU said such a scheme was an essential part of its energy policy: “Smart, sustainable and fully interconnected transport, energy and digital networks are a necessary condition for the completion of the European single market. Moreover, investments in key infrastructures with strong EU added value can boost Europe’s competitiveness. Such investments in infrastructure are also instrumental in allowing the EU to meet its sustainable growth objectives outlined in the Europe 2020 Strategy and the EU’s ‘20-20-20’ objectives in the area of energy policy and climate action. Considerable investment needs have been identified for the three sectors. The respective sectoral guidelines (such as the energy infrastructure guidelines) provide the policy framework for the implementation of European priorities.”

The report added: “For electricity, implementation of BEMIP Action Plan – despite the new issues and problems – is broadly on track and according to schedule. Full implementation will be significantly impacted by the findings of the Baltic synchronisation study and the final agreement with Russia and Belarus on Baltic system operation. Close monitoring of Baltic States synchronisation process is to be ensured.”

Such plans have worried Russia, however, because they may reduce Eastern Europe’s reliance on its energy. In light of Moscow’s meddling in Ukraine, this may not be a bad thing.

Plugging in

The need for a coherent strategy is essential to getting Europe’s energy market connected and running in an efficient manner. Many are echoing Šefcˇovicˇ’s calls for such a policy. The UK’s Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change, Ed Davey, said in a report published in January 2014 that Europe required a giant network of electricity interconnectors in order to solve the problem of rising energy prices: “Literally in the last three or four years, there has been a complete change in the differential between the North American price for gas and energy and the EU price for gas and energy. That represents a strategic change in the terms of trade and is very significant. The EU needs to respond to this very quickly.”

Davey added that a range of interconnectors were needed, not least between Spain and France: “We need much better grid interconnectors around Europe to enable energy to flow across the EU. Connecting the UK with mainland Europe, and different parts of the periphery of Europe with Central Europe. We need Eastern and Central Europe to be better connected with Germany and France and we need the Iberian Peninsula to be better connected through France.”

The UK could, however, offer Spain an alternative to its woes with France. The Spanish Government is thought to be considering a mammoth 895km link across the Bay of Biscay to the UK, at a cost of around €2.5bn. Both Spain and Portugal have sought compulsory targets on building cross-border cables and pipes, allowing them to export at least 15 percent of their spare energy capacity.

Others in the private sector agree a properly connected grid throughout Europe will deliver the sort of energy independence and security the EU has been striving for. Ben Goldsmith, founder of clean energy investment firm WHEB Partners, says: “The development of a fully integrated European grid is a key tool for tackling the issue of intermittency of supply of electricity from renewable sources. An integrated European grid will allow the sunny south to share summer electricity surpluses with the north, and the windy north to share winter surpluses with the south. We cannot get to the promised land of a diversity of sources of electricity across Europe, bringing us true energy resilience, without a fully integrated European grid.”

Europe’s infrastructure plans

Germany

Berlin has been reticent to back sanctions against Russia, dependent as it is on Moscow-supplied energy

Russia

Vladimir Putin and his government will be watching these plans with interest. Russian aggression in Ukraine has heightened European calls for energy independence. If achieved, it could rob Russia of a key market and draw countries on the European periphery further away from Moscow

1. NorthConnect

The £1.75bn Scotland-Norway interconnector is set for completion in 2020

2. Estlink2

As part of the Baltic Energy Market Interconnection Plan (BEMIP), this link to Finland will draw Estonia into the European shared energy market

3. HVDC Norway-Great Britain

At 442 miles, this will be the longest underwater cable in the world when completed in 2020. As well as linking Norway and the UK, the cable could potentially reach out to North Sea utilities

4. NordBalt

This Sweden-Lithuania interconnector is the second major component of BEMIP

5. Nordlink/NorGer

Though not an EU member state, Norway has strong economic and energy links with Europe. Two 1,400 MW cables will provide electrical links between Norway and Germany

6. Potential Spanish-British workaround

An 895km cable link across the Bay of Biscay to the UK could offer the Spanish a way of working around French intransigence

7. Trans-Pyrenees link

The French have blocked Spanish plans for a link between the two countries for decades, effectively locking Spain and Portugal out of the shared energy market. Ostensibly, the French refusal is due to cost and potential damage to the landscape, but many suggest it is actually to protect the country’s delicate domestic energy market