More and more people are developing malignant melanomas, the aggressive black skin cancer. Ultraviolet (UV) light causes such skin tumours and ages the skin, but we also need it to produce vitamin B and to boost our mood. Half an hour of UV exposure a day is recommended: further UV exposure should be blocked by sunscreens.

There are chemical sunscreens that absorb the UV light: they penetrate the skin and undergo chemical transformations that make them effective. Because of this, most lotions should be applied 30 minutes before sun exposure – but it also means some will lose their protective qualities after as little as an hour.

Nanocosmetics is becoming a major industry and sunscreen sales are worth billions of euros a year

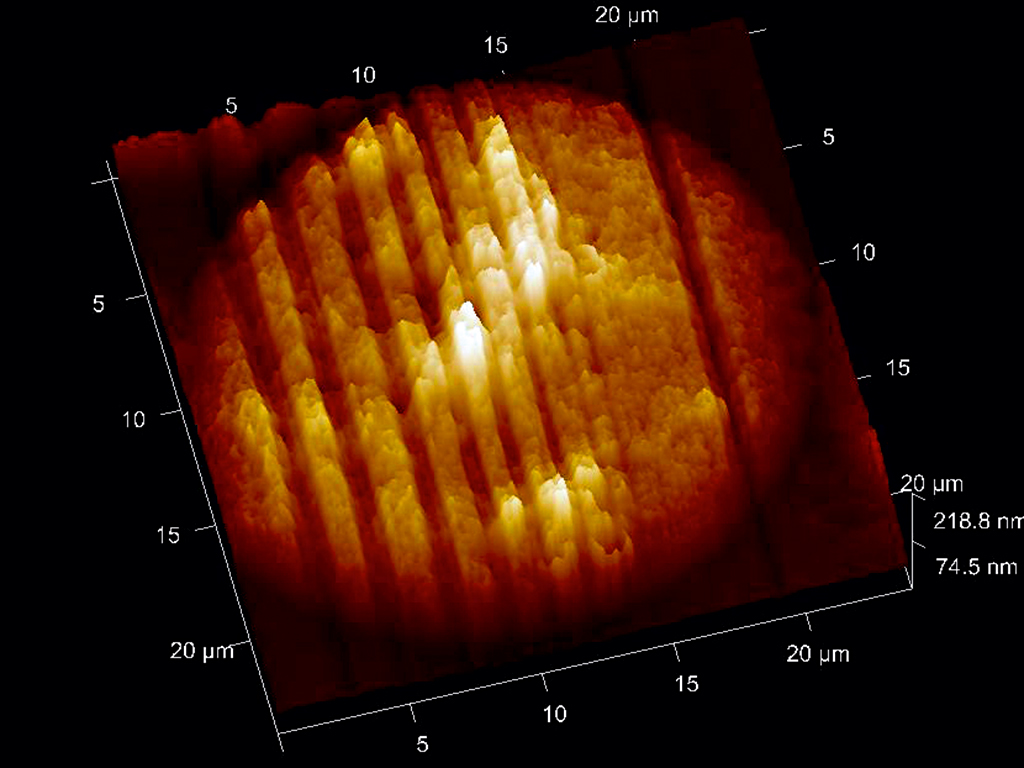

More stable are ‘physical barrier’ sunscreens, sometimes called sunblocks. They contain titanium dioxide and zinc oxide, which reflect UV and work immediately – but particles larger than 250nm tint the skin white and are therefore unpopular with consumers. Applying a reasonably transparent skin protection based on nanoparticles (NP) can solve this cosmetic drawback. Properties of NP vary by size, shape and coating: particles sized around 30nm provide greater UVB but less UVA protection than 200nm particles.

Nanocosmetics is becoming a major industry and sunscreen sales are worth billions of euros a year. Nanoscale zinc was recently approved for use in European sunscreens, but not in sprays or powders, as there is still uncertainty about how much of a risk it poses to the environment and consumers. It’s assumed most NPs remain on the skin’s surface unless washed away and do not penetrate into the skin: if some do enter the epidermis it’s assumed they are dissolved into harmless zinc ions. However, most nanosafety studies have only been performed on skin biopsies or on pigs, and not on human volunteers.

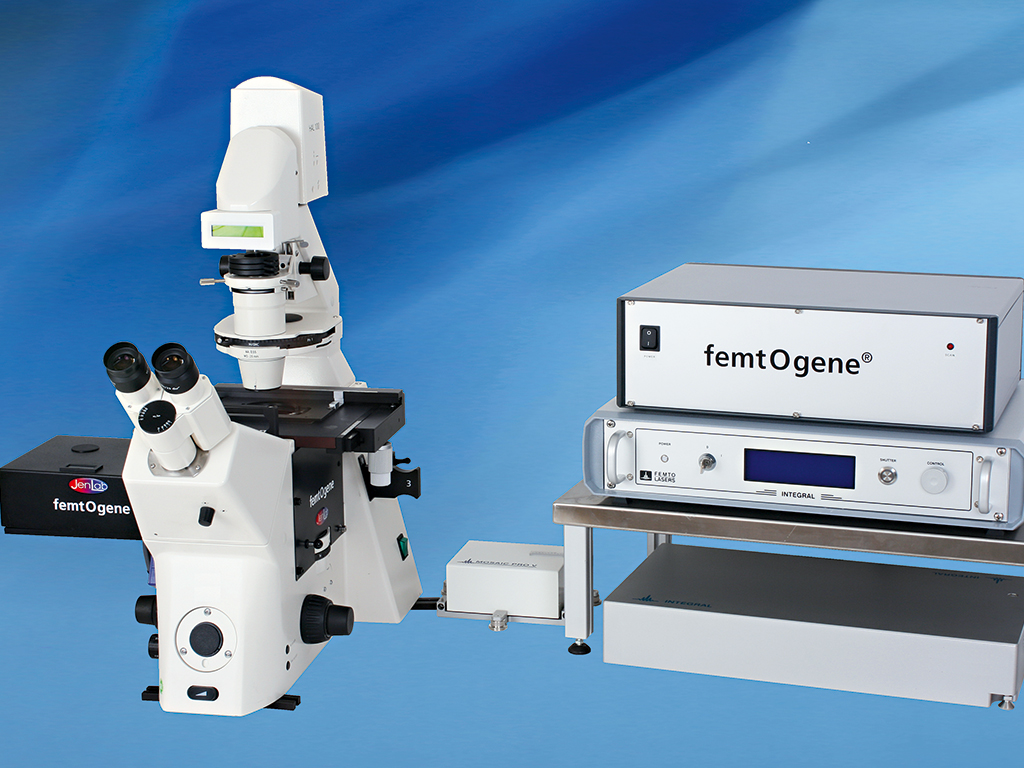

JenLab’s recently developed multiphoton tomograph allows an exact view of what is going on. The particles can be tracked on top of and within the skin; their accumulation in the hair shafts and their interaction with living cells can both be monitored. JenLab’s researchers work with Professor Michael Roberts, who has carried out multiphoton studies at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane, the ‘world capital of melanoma’, where sunscreens are part of daily life. The researchers track NPs in healthy volunteers of different skin types. They found 99 percent of NPs stay on the skin’s surface. However, a significant number of NPs were found in the skin of patients suffering from dermatitis. Nowadays, many cosmetic companies test their products with JenLab’s certified femtosecond laser multiphoton tomographs – an achievement for which the company has been awarded the 2014 New Economy Award for Best Medical Diagnostics Company.

Nanosurgery

When working with near-infrared femtosecond lasers and NPs, the researchers at JenLab found another astonishing effect: gold nanoparticles served as light antennae and nanolenses of light. The NPs collected, focused and amplified light. Furthermore, under certain parameters, they induced highly localised destructive effects. Together with scientists from the Institute of Photonic Technology, JenLab optimised the nanoprocessing particle by adding two types of coating: one coating was applied to change the absorption behaviour by adding silver; the other by adding artificial DNA to functionalise and force it to bind to a certain genomic region of the human chromosome 1.

When exposing the whole chromosome to intense laser light, nothing happened to the DNA without the nanoparticle. With the nanoparticle, however, a 40nm hole appeared, just at the site where the NP was bound to part of the chromosome, 20 times smaller than the laser wavelength. This was the smallest hole ever drilled with a laser beam. This new technology opens the way to highly precise optical molecular surgery and high-speed parallel nanoprocessing with functionalised nanoparticles. JenLab owns the patents for this novel technology.

Femtosecond lasers can even work as nanotools without the use of nanoparticles. JenLab developed the first femtosecond laser nanoprocessing microscope, ‘FemtOcut’, which is able to cut, drill and ablate with sub-100nm precision. This novel microscope has been used to perform completely non-invasive nanosurgery inside living cells by dissecting metaphase chromosomes, and to ‘knock out’ single mitochondria without destroying the surrounding membrane. The cell survived.

Targeted transfection

A very promising application of femtosecond laser nanosurgery is targeted transfection. The femtosecond laser beam drills a transient sub-100 nanometer hole in the cellular membrane to allow molecules such as microRNA or DNA to be entered into the cell’s cytoplasm. Typically, the cell closes the membrane within five seconds through its own self-repair mechanism. In this way, it is possible to transfect cells without the use of viruses, or electrical or chemical means.

In order to obtain high transfection efficiencies in sensitive stem cells, JenLab developed the compact transportable ‘FemtOgene’ microscope, which uses extremely ultrashort laser pulses. Laser pulses as short as 12 femtoseconds, in combination with ZEISS optics, are employed to realise safe laser transfection at low milliwatt laser powers. JenLab’s software is able to recognise cells, to focus on the membrane and to ‘shoot’ transient holes. Up to 200 cells per minute can be transfected with a survival rate of more than 90 percent.

In order to realise higher cell numbers, femtosecond laser transfection can also be performed in a special flow cytometer.

Currently, groups in the US, Canada, the UK, South Africa and Germany optimise the transfection protocols. JenLab owns the worldwide patents for femtosecond laser transfection.

Optical reprogramming and stem cells

The 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to researchers Sir John B Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. The laureates employed viruses to transfect skin cells with a cocktail of four genes, and to force them to ‘re-develop’ and become pluripotent stem cells that are able to differentiate into different cell types and tissues including skin, heart and blood. This reprogramming of own adult cells has major advantages, such as helping us avoid the use of embryonic and adult stem cells from other donors. A major disadvantage so far is the use of viruses that may prevent clinical applications. JenLab’s femtosecond laser transfection technology may overcome this problem. Currently, a team from the Universities at Saarbrücken and Tübingen is trying to realise virus-free femtosecond laser reprogramming and direct programming. If a success, it would be a major step towards clinical application of this groundbreaking work.

JenLab’s award-winning multiphoton tomograph can be used for the early detection of skin cancer. Single cancer cells, such as strong fluorescent melanocytes, can be easily recognised with the femtosecond laser tomograph. What about destroying the cancer cell immediately when detected? Researchers are working on a future two-mode operation system of the femtosecond laser device. In the first mode, cancer cells can be imaged in three dimensions. Sophisticated image processing should recognise the tumour borders. In the second mode, the intensity of the laser beam should be significantly increased to become a highly precise nanoscalpel. This precise laser tool should destroy the cells of interest while leaving the surrounding cells alive. The realisation of this surgical tool is still, however, a long way off.

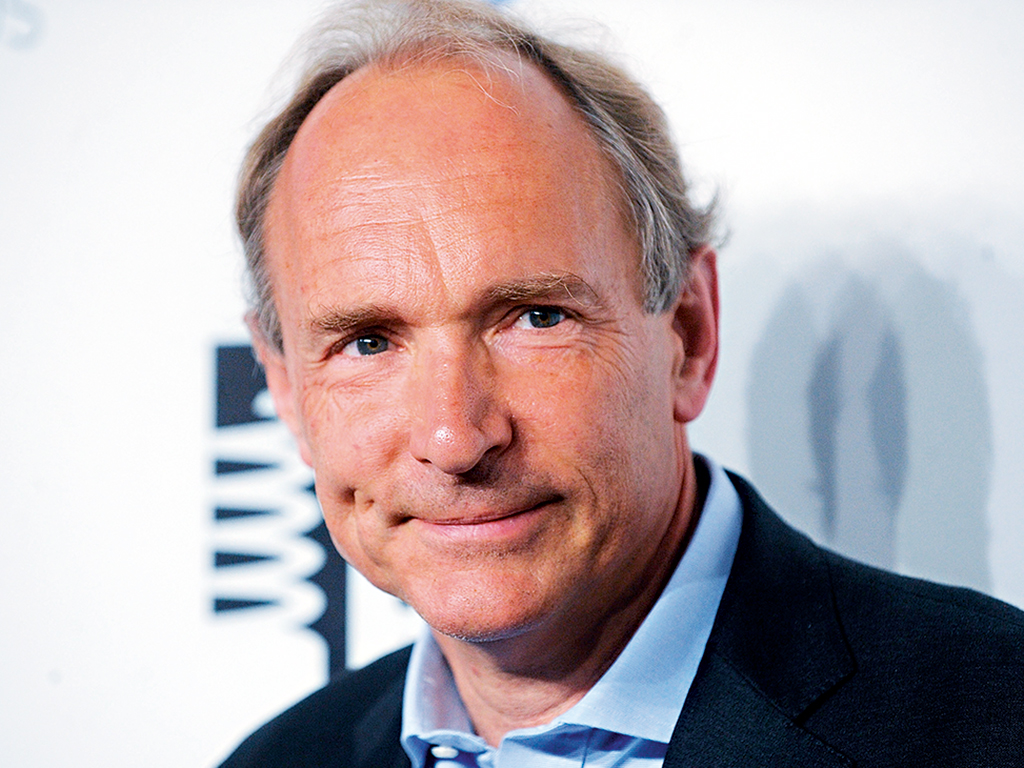

While former US Vice President and environmental campaigner Al Gore has been heralded many as the father of the web, that accolade actually belongs to an altruistic British computer scientist called Tim Berners-Lee. It was while working as an independent contractor at Europe’s particle physics laboratory, CERN, in 1980 that Berners-Lee developed the worldwide web.

While former US Vice President and environmental campaigner Al Gore has been heralded many as the father of the web, that accolade actually belongs to an altruistic British computer scientist called Tim Berners-Lee. It was while working as an independent contractor at Europe’s particle physics laboratory, CERN, in 1980 that Berners-Lee developed the worldwide web. An invention that paved the way for the industrialisation of the world, the steam engine can be claimed by a number of people. Spanish inventor Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont first patented a steam engine design in 1606, before Thomas Savery patented a steam pump in 1698. However, the first commercial use of a steam engine didn’t occur until 1712, when English inventor Thomas Newcomen developed one that could be used to pump water out of a mine. While the steam engine was put to use in a number ways during the 18th century, it wasn’t until the turn of the 19th that Richard Trevithick, an inventor and mining engineer from Cornwall, devised a contraption powerful enough revolutionise the world. His work on steam power proved crucial to the development of the technology for mass transportation, but is rarely spoken of nowadays.

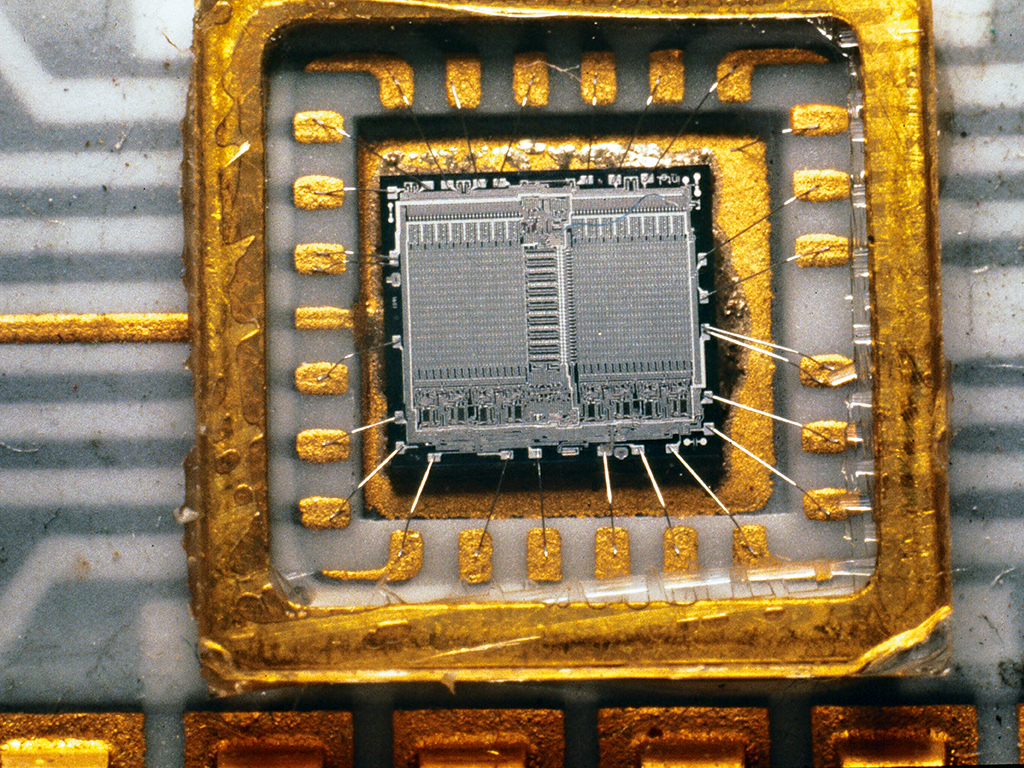

An invention that paved the way for the industrialisation of the world, the steam engine can be claimed by a number of people. Spanish inventor Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont first patented a steam engine design in 1606, before Thomas Savery patented a steam pump in 1698. However, the first commercial use of a steam engine didn’t occur until 1712, when English inventor Thomas Newcomen developed one that could be used to pump water out of a mine. While the steam engine was put to use in a number ways during the 18th century, it wasn’t until the turn of the 19th that Richard Trevithick, an inventor and mining engineer from Cornwall, devised a contraption powerful enough revolutionise the world. His work on steam power proved crucial to the development of the technology for mass transportation, but is rarely spoken of nowadays. The impact the microchip has had on the world cannot be understated. An integral component of a staggering array of devices – including ATMs, digital watches, computers, smartphones and video game consoles – the microchip is what binds all these technologies together and allows them to operate.

The impact the microchip has had on the world cannot be understated. An integral component of a staggering array of devices – including ATMs, digital watches, computers, smartphones and video game consoles – the microchip is what binds all these technologies together and allows them to operate. You would think something so commonly used as the match would have made its inventor an absolute fortune. However, the man responsible for creating the first friction match considered the invention – created by accident – “too trivial” to warrant patenting.

You would think something so commonly used as the match would have made its inventor an absolute fortune. However, the man responsible for creating the first friction match considered the invention – created by accident – “too trivial” to warrant patenting.