The one trillion dollar war

The growth of cyber crime has caught the attention of many world-leading organisations. Some have gone so far as to declare the start of a ‘cyber war’

Housed in the nuclear-safe remains of a long-abandoned military bunker, a select contingent of hackers negotiated the effective slowdown of the internet. The shady – though no less sagacious – group slowed governmental, commercial and personal activity worldwide. While few – if any – were left tending physical wounds, the debacle revealed the unseen structural weaknesses of a platform harbouring – put lightly – world-breaking assets.

Housed in the nuclear-safe remains of a long-abandoned military bunker, a select contingent of hackers negotiated the effective slowdown of the internet. The shady – though no less sagacious – group slowed governmental, commercial and personal activity worldwide. While few – if any – were left tending physical wounds, the debacle revealed the unseen structural weaknesses of a platform harbouring – put lightly – world-breaking assets.

These are the circumstances alleged to have involved internet service provider CyberBunker and an internet support service known as the Spamhaus Project. Spamhaus, having blacklisted CyberBunker on account of its suspected distribution of spam, found itself the victim of an unprecedented hacking offensive – otherwise termed a ‘distributed denial of service’ (DDoS) attack.

The consequences have been compared to a “virtual nuclear bomb”, as huge streams of data flooded the site (peaking at 300 billion bits per second) and, in effect, threatened to overwhelm the internet. Testament to the scale of the damage is that Google offered its near-limitless resources for use in combating the DDoS attack. The incident has been referred to as an unnerving indication of the potential influence wielded by cyber criminals.

In the typically theatrical spirit of similar attacks – such as those committed by Anonymous, Lulzsec and Honker Union – images of CyberBunker’s headquarters were subsequently circulated online – as were written details of an attempted SWAT team raid thwarted by the bunker’s blast-resistant doors.

Though the somewhat fabulist debacle appears entirely misrepresentative of the all-too-serious repercussions of the incident, CyberBunker’s cavorting is indicative of the relatively free rein cyber criminals have in manipulating world-leading organisations. They view cyberspace as if it is a parallel universe, in which there are no real-world consequences.

Commercial value

Cyberspace is an anarchic platform – the incidents populating it ranging from acts of protest to invasions of state sovereignty and outright devastation. Cyber crime is a practice adopted by organised groups and amateurs alike. While most operate at street level, a few act under the utmost anonymity for fear of their victims retaliating.

Perhaps the most common mode of cyber crime is copyright infringement. It has opened up a huge number of commercial opportunities to those participating, while crippling the viability of a fair few legitimate enterprises. Reuters claims Chinese piracy and counterfeiting alone costs the US economy billions of dollars a year, and if combatted, could create a further 2.1 million US jobs.

Piracy of this sort is a seemingly intractable problem. It has become embedded in popular culture and has been effectively decriminalised the world over. Though the costs of piracy are near impossible to calculate, it can inflict huge financial penalties on effected parties – Time Warner estimated almost 95 percent of its films watched in China have either been illegally downloaded or resold as counterfeit equivalents.

Nevertheless, the effects of copyright infringement are relatively small fry compared to the gross financial ramifications for the governments, corporations and military organisations being hacked for commercial gain. More advanced hacking groups aim to intercept and retain valuable resources that would otherwise remain undisclosed by holding parties.

This manner of intrusion is typically negotiated by means of board-level directors opening an email and unwittingly permitting hackers access to commercially rich aspects of the company’s network. Hackers have been found to have hidden in companies’ IT systems for as long as four years, discreetly accessing vital and expensive information.

Breaking the bank

Hackers also hit financial institutions through similarly perverse methods of intrusion. Perhaps the most common means is the creation of hundreds of online accounts that are then used to trade money and build up a credit history strong enough to qualify for colossal loans. Credit is then withdrawn, never to be repaid – the registered holders being fictional entities.

Recent hacking breaches have affected a number of western companies, making for a frightening insight into the potential power cyber criminals can have in destabilising – or else spurring – fundamental pillars of the corporate sphere. As a host of US companies – including Apple, Google and Facebook – fell foul of malicious software intrusions in February, security company Mandiant claimed to have pinpointed the source of the attacks as a state-run office building in Shanghai.

The US company claimed those operating from the People’s Liberation Army base had “systematically stolen hundreds of terabytes of data” from over 140 global organisations. The occupants were deemed by Mandiant to number among the most prolific hacking groups in the world “in terms of quantity of information stolen”. Those involved now stand accused of stealing billions of dollars worth of commercial and military assets.

Hacks of this nature have led many to speculate on the existence of organisations whose niche is trading the compromised systems of world-leading organisations. Mark Ward, Technology Correspondent for the BBC, suggests criminals are gathering the details of vulnerable servers from the online community – effectively crowdsourcing a database of IP addresses for sale to the highest bidder. Security firm Trend Micro has said Russia is at the centre of a networked criminal economy in which “any and every cybe crime service is on sale” – a frightening insight into the commercialisation of compromised company networks.

A matter of trust

While organisations have historically been reluctant to report misgivings of this sort – keen as they are to uphold their reputation with customers – many have recently been pressed to publically concede the intrusion of malicious hackers. Ross Parsell, Director of Cyber Security at Thales, says he’s seen a “70 percent increase in interest and conversations” with potential clients regarding the improvement of their security systems over the past 18 months.

A growing readiness to admit these cases is casting a more accurate – though equally disturbing – light on the actual scale and frequency of these attacks. While researchers at the University of Cambridge claim in their report ‘Measuring the Cost of Cyber Crime’ that direct monetary loss to the average UK consumer amounts to a mere £10 a year, the actual costs are at least tenfold; that sum includes recuperation, security measures and a severe loss of consumer confidence in the affected businesses.

In 2011, Sony was forced to spend $171m to recover leaked customer records – a concession that damaged the company’s credibility. A study conducted by the Reputation Institute has since revealed only 67 percent of customers are willing to recommend Sony’s services – a marked decline from 79 percent prior to the incident.

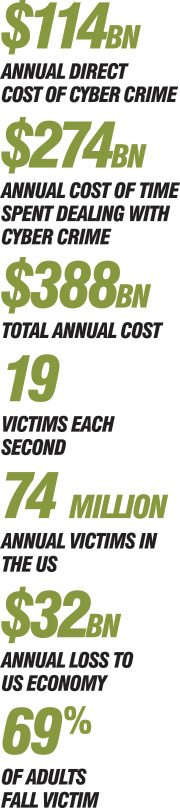

Though hacking is generally an unquantifiable process, cyber crime is thought by the Cabinet Office to cost the UK economy £27bn. The White House believes it costs the global economy $1trn, offering a disturbing glimpse at the grave damage dealt by the practice.

At the brink

Cyber crime has, in the eyes of some, evolved into a form of terrorism and espionage. The UK government ranked the practice a Tier 1 risk to national security. The exponential increase in instances of cyber crime – as well as the increasing costs to affected parties – has resulted in a climate of fear. Many believe the world is now stood on the edge of a ‘cyber war’.

State-sponsored cyber attacks have become increasingly prevalent in recent years. In addition to Mandiant’s discovery of a ‘cyber espionage’ unit in China, The New York Times last year confirmed the US and Israeli governments’ collaboration in attacking Iran’s critical infrastructure – most notably through lesser-known vulnerabilities in Microsoft and Siemens devices and software. Though such attacks appear relatively benign compared to physical warfare, many see cyber war as a genuine and dangerous threat.

While cyber warfare seems like something out of science fiction or general make-believe, the US Department of Defence is nonetheless looking to invest considerable sums in protecting against it. The organisation revealed in April that it is spending $30m on establishing cyber war operations for both the army and air force – primarily to acquire adequate hardware and software tools for hackers.

The new Cold War

The New Digital Age, written by Google’s Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt and Ideas Director Jared Cohen, warns of the potential for “perpetual, permanent low-grade cyber war” in the near future. They liken its potential to the Cold War, saying: “Today, only a small number of states have the capacity to launch large-scale cyber attacks – the lack of fast networks and technical talent holds others back – but in the future there will be dozens more participating, either offensively or defensively.”

However, whereas the world’s foremost superpowers opposed each other in the Cold War, a cyber war would involve emerging economies; developed countries using them as bases or proxies. Schmidt and Cohen claim: “Our increasing entwining of our lives with digital information systems leaves us more vulnerable with each click. And with so many countries coming online in the near future, those vulnerabilities will only expand and become more complicated.”

Although the reasons are complex, the US and China are undoubtedly engaged in a cyber conflict of sorts. Adam Segal of the Council on Foreign Relations says it is “likely to remain below a threshold that would provoke military conflict”. China, though not for lack of notoriety, has yet to depart from mere acts of theft, or inflict terminal or lasting damage on affected parties.

Regardless, technologically advanced nations such as the US and China will doubtless persist in testing the boundaries of cyberspace. The future capabilities of independent cyber criminals are less certain – but if they can slow down the entire internet today, it would be unwise to play down what they might be capable of tomorrow.