Australia digs while the world burns

The Australian government has been busy challenging and reversing much of the environmental protection legislation put in place by previous administrations

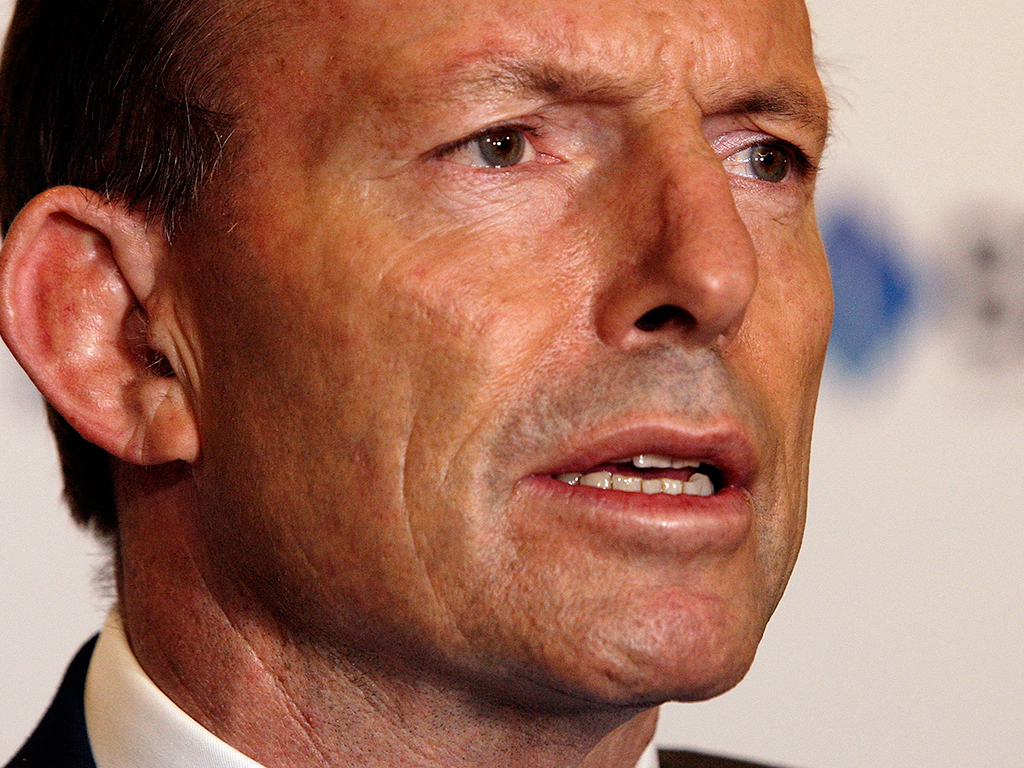

Prime Minister Tony Abbott has dismantled a number of Australia’s green policies

Australia is home to one of the most diverse ecosystems in the world: from kangaroos to giant mosquitos, from the Great Barrier Reef to the world’s largest mangrove. It is certainly one of most exuberant countries in the world when it comes to wildlife. According to the Wilderness Society, there are only 17 countries classed as ‘megadiverse’ – that is, countries with an “extraordinarily high levels of biodiversity”. Australia is one of only two developed nations that fall into the category. Collectively, these nations hold around two thirds of the world’s biodiversity. Australia has more species endemic to its shores than 98 percent of the world’s countries. Most people agree it is a veritable treasure trove of plant and animal life, of incalculable value, and that this biodiversity should be preserved at any cost. Prime Minister Tony Abbott, however, is not most people.

Abbott has been carefully cultivating a dangerous record when it comes to environmental policies. Since assuming office in 2013, he and Environment Minister Greg Hunt have campaigned for the delisting of rare Tasmanian forests as a World Heritage site, approved the exemption of Western Australia from federal laws protecting endangered white sharks, and approved construction work on ports and coal terminals that will dredge the sea bed and potentially harm the Great Barrier Reef. These have not been popular moves, but Abbott has ploughed ahead, undeterred.

The Abbott government has consistently made the case that environmental concerns will always lose when pitted against economic benefits

“This crowd have been in office for less than six months. Imagine the damage they can do in three years,” wrote a disgruntled reader in The Sydney Morning Herald. “We, the people, do not want your bloody coal terminal. You, the decision makers, should be forced to pay for your avarice and environmental vandalism,” wrote another.

A recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has given some credence to the concerns expressed by the zealous readers of the Herald. In its Climate Change 2014 report, the organisation is clear about the need to lower global carbon emissions, and cited carbon pricing as a positive step towards achieving that goal. It is in direct contradiction to a recent policy reversal by the Australian government in which the cap-and-trade emissions trading scheme was scrapped entirely.

Curbing emissions

The IPCC report is primarily concerned with the mitigation of the effects carbon emissions are already having on the global climate. Research by over 1,250 specialists concluded that, to limit average temperature rises to only two degrees above pre-industrial levels, there would need to be a drastic increase in the use of low-carbon energy by 2050. The IPCC report concludes the required investment to power the shift towards lower-carbon energy consumption would shave only 0.06 percent off expected annual economic growth rates. In the meantime, carbon pricing can be an efficient and viable solution to keeping emissions down.

“Carbon pricing was a positive step in the right direction and if Australia did link it to the European scheme, the price wouldn’t be high. Scrapping it is seen as a backwards step,” Professor David Stern, one of the lead authors of the IPCC report and lecturer at the Australian National University told The Guardian. “It’s a cost-effective incentive for everyone to look for their best option to lower emissions. Most of the mentions of Australia in the IPCC report are around its emissions trading scheme. The report makes clear that carbon pricing is a cost-effective model, if done correctly.”

The carbon pricing policy was launched in Australia under the previous Labour government, but Abbott’s Liberal-led coalition has long taken issue with it. Dubbed ‘the carbon tax’ by its opponents, the policy is now being replaced altogether.

Hunt recently announced an extension of the pre-existing Emissions Reduction Fund, which includes cash rewards for private companies that lower emissions, as well as a tree-planting initiative.

“The carbon tax was a AUD7.6bn hit on the Australian economy in its first year of operation, yet there was no meaningful reduction in emissions. The carbon tax truly is a policy failure,” said Hunt in a statement. “The Australian Government is a step closer to replacing the destructive carbon tax with an effective, practical and simple approach to reduce emissions. The Emissions Reduction Fund is the centrepiece of the Coalition Government’s Direct Action Plan to reduce Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions by five percent below 2000 levels by 2020.”

However, critics of similar schemes, such as Stern, have suggested such reward schemes as the one currently being proposed by Hunt and the Australian government actually cost more in the long run as taxes need to be raised to pay for the subsidies, while carbon trading schemes actually generate revenue. “The carbon price has long-term benefits for our nation and Australians can see that,” WWF-Australia Climate Change National Manager Kellie Caught told The Australian. “Not only does the carbon price raise revenue for the budget, it tackles climate change by making polluters pay, drives investment in renewable energy, and helps save the Great Barrier Reef.”

Coal heart

Australia remains a major coal producer, however, and up to 85 percent of the country’s energy comes from coal plants. In the latest budget, the Abbott government granted the mining industry handouts worth over AUD100m to keep exploring for new sources of coal and iron ore. Plans are afoot for the opening of nine mines in the near future, which could yield 27 billion tonnes of coal. With a combined area of 96,000sq mi, the Galilee Basin is among the biggest coal deposits in the world. But the University of Technology, Sydney, has warned that, if all the plans are approved and mines are excavated, the extra yearly emissions generated will equate to putting an additional 7.59 million cars on the road within the next decade and a half.

The Galilee Basin mines are being developed by Gina Rinehart, the wealthiest woman in the world, along with the Adani Group of India. Three large mines are already being built: the first of which will be about 15-miles wide when finished. The Queensland Government recently granted approval for the AUD16.5bn project, despite widespread condemnation from environmental experts. There are concerns about the effect the mines will have on groundwater due to the mines’ close proximity to the underlying Great Artesian Basin. And, though the mines themselves are problematic from an environmental perspective, the impact the mined coal will have is almost immeasurable.

Most of the coal mined in Galilee will be exported, meaning an additional 4,800 ships will travel through the Great Barrier Reef each year. Specialised ports on the Queensland coast are being expanded to service the Galilee Basin mines. Up to 150 million tonnes of material will be dredged from around the reef, posing an “unprecedented” threat to the corals, according to a report by the Australian Marine Conservation Society. “The Great Barrier Reef is expected to degrade under all climate change scenarios, reducing its attractiveness,” the report states. “Evidence of the ability of corals to adapt to rising temperatures and acidification is limited and appears insufficient to offset the detrimental effects of warming and acidification.”

But mining remains a powerful and lucrative industry in Australia, and, as growth forecasts continue to be revised down, it is unlikely the government will be willing to antagonise it. Abbott’s coalition has set a target of reducing carbon emissions by five percent of what they were in 2000 – a figure roughly in line with other similarly developed countries. But, according to Australia’s independent Climate Change Authority, the country’s target should be closer to 15 percent of 2000 levels in order to be “credible”.

It is unlikely the government will review its targets. The Abbott government has consistently made the case that environmental concerns will always lose when pitted against economic benefits: a policy that might be popular with industry chiefs, but which is unlikely to be sustainable in the long term. Numerous steps have been taken to speed up the dismantling of environmental safeguards; in the new budget, Abbott has confirmed the long-rumoured scrapping of the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), despite the agency still having about AUD1bn in unallocated funds. When it was founded less than two years ago, ARENA was given an AUD2.5bn budget to foment the development of renewable energy in the country, support research and share expertise. “Axing the Australian Renewable Energy Agency is a damning reflection on the backward thinking of the Abbott government. The Abbott government has no vision for the future, or indeed, the present day,” the leader of the Green Party, Christine Milne, told the Environment News Service.

Against the grain

ARENA is not, by a long shot, the only environmental initiative on the chopping block. The Clean Energy Finance Corporation, launched last year and responsible for AUD10bn in investment in clean energy companies, is also being discarded. The coalition is also reviewing the Renewable Energy Target, a measure Abbott’s Liberal Party ostensibly backed before the election to support the goal of supplying 41,000GWh of clean energy by 2020. “What’s disappointing here is that the coalition really went out of its way prior to the election to restate their commitment to ARENA,” Kane Thornton, Deputy Chief Executive of the Clean Energy Council, told The Sydney Morning Herald.

Meanwhile, the world’s leading climate change experts and economists are all standing behind reports such as the IPCC’s, which call for a drastic reduction in carbon emissions and a revaluation of the energy industry. But the Australian government seems resolute in playing by its own rules. It is a deeply problematic attitude. Because the country has been blessed with such abundant resources, decisions taken by local government can have a global impact. If the Galilee Basin is explored in the way Rinehart and the Adani Group hope it might, the consequences of the copious unmitigated carbon emissions will be felt everywhere.

The time for the unbridled exploration of coal is long passed; politicians, economists and scientists agree. Abbott, Hunt, and the rest of Australia’s coalition government and their coal mining chums should heed the advice of the IPCC and the Climate Change Authority and review their policies. Owen Pascoe, WWF Australian spokesperson asked it best in a statement: “The IPCC has made it clear what the world needs to do – the question for Australia is now what sort of country are we going to be? Are we going to sit back and hope the United States, Europe and China will do the work to save our Great Barrier Reef and protect our country – or are we going to pitch in and do our fair share?”