China gives a dam about improving its green energy infrastructure

China’s Three Gorges Dam, a project so large it has affected the speed of the Earth’s rotation, is capable of generating huge quantities of renewable energy. It has also caused social and environmental disruption to the local area

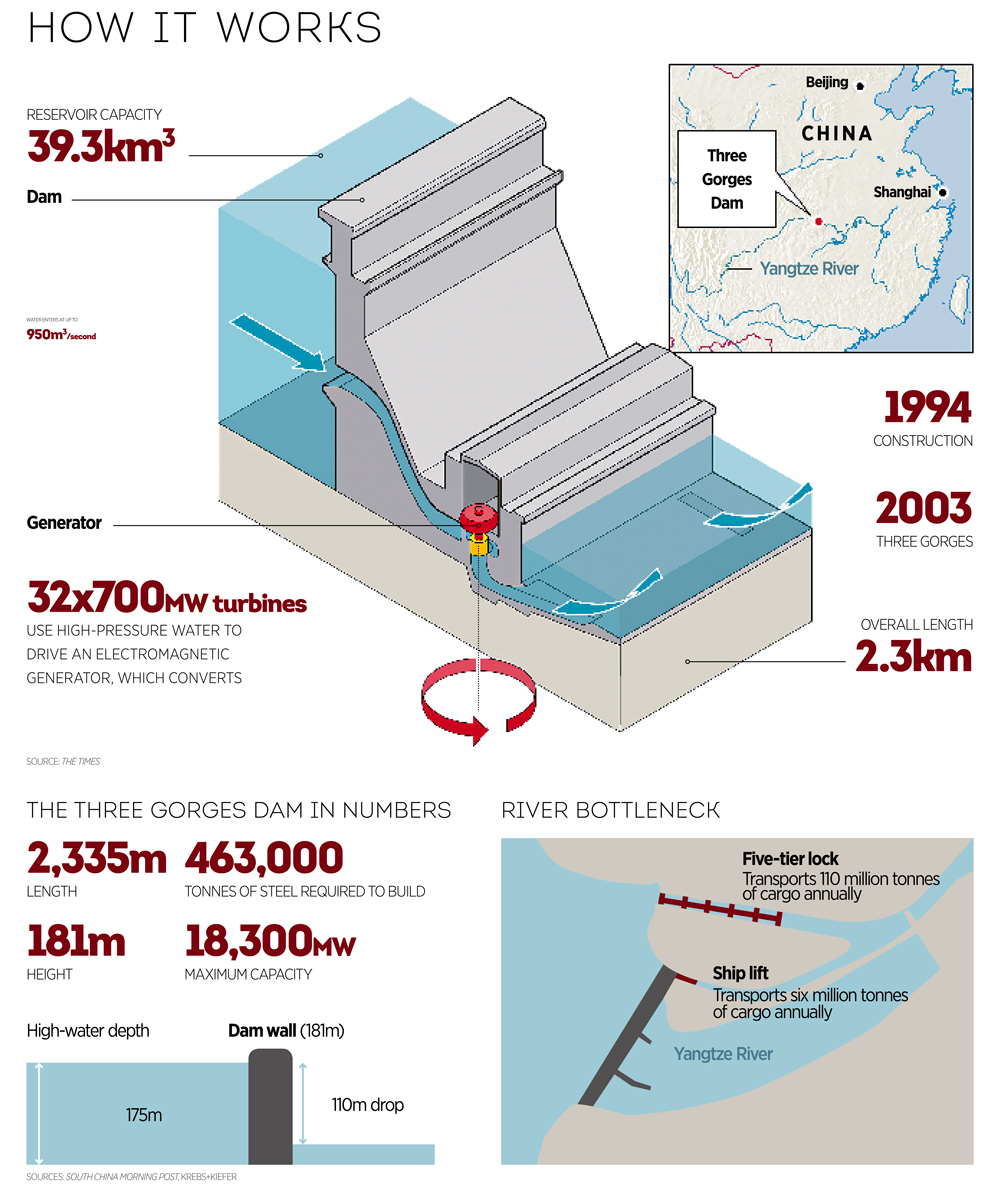

The dam has a maximum electrical capacity of 18,300MW, produced by 32 generators that use high-pressure water to spin huge turbines at a rate of 75 revolutions per minute

An engineering project of bewildering size, some of the statistics pertaining to the Three Gorges Dam are hard to believe. The dam, which bestrides the Yangtze River in Central China, is 7,661ft long and more than 600ft high. It required 463,000 tonnes of steel to build and is so large that the mass of water that built up behind it caused the rotation of the Earth to slow down slightly.

For now, the dam is the largest in the world, but that may not be the case for much longer. Proposals are being explored for the construction of the Grand Inga Dam, which would use the power of the Congo River to generate 40,000MW of electricity – more than twice the amount currently produced by the Three Gorges Dam.

If plans to build another hydroelectric megastructure do get the go-ahead, they will no doubt benefit from the successes and pitfalls that the Three Gorges Dam has already experienced. It is a project that has attracted controversy for economic, social and environmental reasons.

The project’s green credentials ring rather hollow given the ecological damage it has already caused

Need a lift?

Construction of the Three Gorges Dam was completed in stages, taking 17 years in total. Today, the dam has a maximum electrical capacity of 18,300MW, produced by 32 generators that use high-pressure water to spin huge turbines at a rate of 75 revolutions per minute. This drives an electromagnetic generator that converts the water’s kinetic energy into electricity.

The Three Gorges project also aims to open up shipping routes to China’s interior. In late 2016, the dam’s hydraulic ship lift was officially launched, boasting the capacity to raise vessels 371ft in order to pass over the dam. The system uses reinforced concrete, cables and counterweights to allow for the passage of ships weighing as much as 3,000 tonnes. While it took ships three to four hours to cross the dam using the previous system of locks, the new method takes just 40 minutes.

The dam’s main goal, however, remains power generation. The project originally aimed to produce around 10 percent of China’s total energy needs, but the country’s rapid economic development has brought this target crashing down.

Outta the dam way

Sustainability was, of course, a major reason for building the dam: not only would it lessen the need for fossil fuels, but it would also reduce the potential for flooding further downstream. However, the project’s green credentials ring rather hollow given the ecological damage it has already caused.

During construction, 1.3 million Chinese citizens were forcibly relocated to make space for the dam’s reservoir. In total, two cities, 11 counties, 116 towns and countless sites of cultural importance were flooded. The risk of geological hazards occurring, principally landslides, has also risen significantly as a result of changes to local water levels.

More trouble arose earlier this year amid claims that the dam was breaking apart. Reports of an impending collapse spread across social media after one Twitter user posted a satellite image purporting to show that the dam had become deformed. Officials were quick to debunk the rumours, stating that any changes to the dam’s structural integrity remained within normal parameters. Hopefully they are right – if the dam were to collapse, the environmental, economic and human damage would be monumental.

Barring catastrophe, then, the Three Gorges Dam will remain the largest hydroelectric plant in the world for the foreseeable future. Even if it is eventually usurped by the Grand Inga Dam or another such structure, it will continue to stand as a testament to humankind’s engineering brilliance; a project of scarcely believable scale.