Deep-sea mining could provide access to a wealth of valuable minerals

Deep-sea mining could help meet mankind’s insatiable thirst for essential minerals and power the green economy of the future. It could also cause irreversible damage to a part of the planet that we know very little about

At the bottom of the ocean resides a wealth of rare minerals that could be the key to powering the global economy of the future. It could also provide a lucrative revenue stream for any organisations that can reach them quickly, cheaply and sustainably

According to NASA and other industry experts, we know more about the Moon than the darkest recesses here on Earth. While 12 individuals have set foot on the lunar surface, only three have visited the deepest part of the ocean. Satellites have mapped the Moon with a pixel scale of around 100m, but the seabed has only been catalogued to a far grainier resolution of 5km.

To take nothing away from man’s astronomical achievements, reaching the bottom of the sea still represents a significant technical challenge. Even if the deepest parts are avoided – including the Mariana Trench and its record depth of 10,994m – travelling to the seabed often means a shadowy descent lasting more than an hour and enduring pressure thousands of times stronger than that found at the Earth’s surface.

As the prospect of deep-sea mining comes closer into view, businesses will begin scrutinising the industry financials in more detail than ever before

Aside from intellectual curiosity, there is one particular factor that is tempting businesses to make this arduous journey: deep-sea mining. At the bottom of the ocean resides a wealth of rare minerals that could be the key to powering the global economy of the future. It could also provide a lucrative revenue stream for any organisations that can reach them as quickly, cheaply and sustainably as possible.

Testing the water

The idea that the ocean floor might host a rich variety of valuable minerals was first considered in 1873, when the HMS Challenger recovered a number of manganese nodules from the bottom of the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans. At the time, the process of dredging the seabed for these minerals was rudimentary and offered little economic value. However, it did spark a curiosity that persists today.

In 1965, John L Mero – recognised by many as the father of ocean mining – conducted more detailed research into the economic potential lying at the bottom of the ocean, and determined that the mining of manganese nodules would become a viable business proposition within just 20 years. His declaration may have been overly optimistic, but it was based on solid economic principles: though later than Mero predicted, today deep-sea mining is gaining traction in the business world.

The Clarion-Clipperton Zone in numbers

4.5m

Square kilometres

15m

Tons of rare earth oxides

16

Number of exploration licences issued by the ISA

“Mining in the deep sea is an extremely technical and difficult thing to do,” Dr Kirsten Thompson, a marine biologist at the University of Exeter, told The New Economy. “The conditions at depths such as 4,000m are extreme, with high pressure, low temperatures and darkness. While commercial mining companies have considered and piloted mining in the past, it is only now that the technology has been developed that might make deep-seabed mining a reality.”

This technology is being deployed by a number of different companies, but perhaps the best known is Canada-based firm Nautilus Minerals. In 2011, Nautilus became the first company to gain deep-sea mining rights, after being granted a 20-year licence for its Solwara 1 project by the government of Papua New Guinea. The fact that Nautilus has only conducted exploration work in the time since the licence was granted is a testament to the technical difficulties surrounding deep-sea mining.

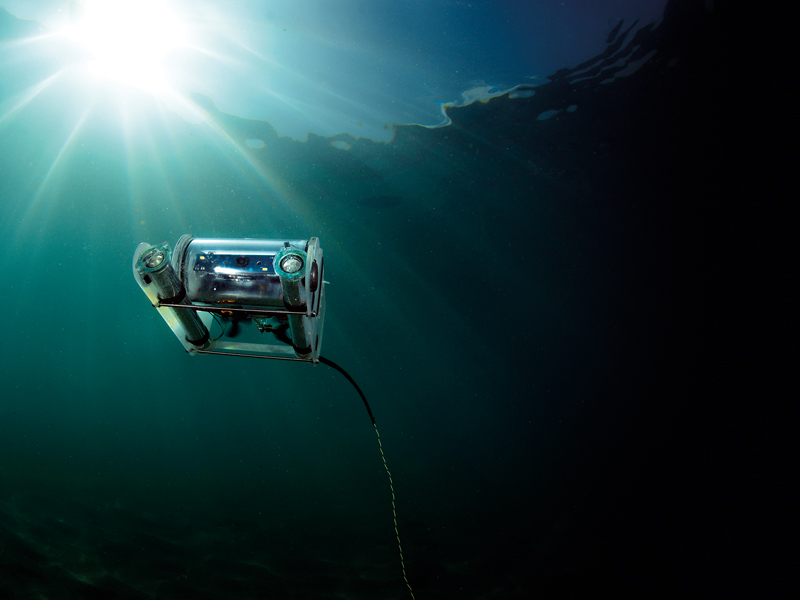

“There are some real technical challenges, and many of our staff and contractors are excited to be involved,” explained John Parianos, Manager of Exploration and Polymetallic Nodules at Nautilus Minerals. “The sea can be a turbulent place to work and most tasks need to be done by remote control in remote locations. Engineering work needs to meet exacting standards and procedures need to be well-thought-through. A lot of what we are developing is of interest to other miners seeking to mine deep underground, for example.”

The company’s exploratory programmes are certainly proving enlightening. Nodule samples have been recovered from the seabed in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the Pacific Ocean and metallurgical test results have yielded information sure to prove vital when drilling does commence. Businesses have waited decades to find a way of turning the idea of deep-sea mining into reality; in light of the potential riches lying on the ocean floor, a delay of a few more years is unlikely to put them off.

Deep pockets

Nevertheless, as the prospect of deep-sea mining comes closer into view, businesses will begin scrutinising the industry financials in more detail than ever before. The economic viability of any project may depend on the unpredictable movements of commodity market prices.

There are three groups of minerals found on the seabed: seafloor massive sulphides, cobalt-rich crusts and polymetallic nodules. Collectively, these can contain rich deposits of copper, manganese, zinc, cobalt, platinum and a host of other valuable metals. Although the price of these minerals remains volatile to an extent, they have stayed relatively stable for some time. Depressed metal prices have slowed the progression of the deep-sea mining industry in the past, but the likelihood of history repeating itself appears slim.

The minerals found underwater may actually be essential if humanity is to successfully transition from a fossil-fuel-based economy to a green one

Many of the minerals found thousands of metres below the water’s surface are absolutely essential to the modern digital economy and are set to remain so for the foreseeable future. In particular, some of the rare earth metals that have been harvested from polymetallic nodules, including erbium, europium and yttrium, play important roles in cutting-edge technologies. While the annual worldwide mine production of rare earth metals currently stands at around 100,000 tons, the CCZ alone is estimated to contain 15 million tons of rare earth oxides.

Global demand for many of the minerals found on the seafloor is already high, and is only travelling in one direction. China currently accounts for more than half of the world’s metal consumption and its economic trajectory means its desire for raw materials is set to rise further. This trend will surely be matched in other developing countries. Economically, deep-sea mining’s time finally appears to have arrived.

Even so, companies that decide to enter this new market must accept a certain degree of risk. The technical sophistication required to reach the ocean’s depths requires a great deal of investment, something that is immediately evident when looking at the three seafloor production tools that Nautilus has commissioned. What’s more, entering into such an experimental field usually means delays, and budget overshoots are to be expected.

As of September 2018, Nautilus has committed to contracts worth $16.7m for the design and build of a seafloor production system, but it’s highly likely that this figure will grow. Nautilus itself recognises that the level of funding it will require is difficult to quantify at this stage.

“Nautilus’ ability to generate revenues and achieve a return on shareholders’ investment must be considered in light of the early stage nature of the Solwara 1 deposit and seafloor resource production in general,” the firm stated in a cautionary note issued last year. “The company is subject to many of the risks common to early-stage enterprises, including personnel limitations, financial risks, metals prices, permitting and other regulatory approvals, the need to raise capital, resource shortages, lack of revenues, equipment failures and potential disputes with, or delays or other failures caused by, third-party contractors or joint venture partners.”

For Nautilus and the small number of other businesses that have decided to make tentative ventures beneath the ocean’s waves, the rewards on offer may make such a high degree of risk palatable. The deep-sea mining industry could be worth as much as $1trn to the US economy each year – the value of all the gold deposits alone on the seafloor is estimated to be around $150trn. It’s not hard to see why investors are getting excited.

A mine of information

However, not everyone is enthused about the potential benefits that could emerge from this fledgeling industry. Environmental concerns abound regarding the possible damage that deep-sea mining projects could have on what are largely unexplored ecosystems. All but one of the 17 exploration licences for polymetallic nodules granted by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) relate to the CCZ, an area spanning 4.5 million square kilometres in the Pacific Ocean that has demonstrated particularly high levels of biodiversity. One recent survey found that 70 percent of the 154 bristle worm species found in the CCZ were previously unknown to science.

“In my opinion, the opposing goals of deep-sea mining and marine conservation cannot be balanced at the moment,” Thompson said. “Many international experts are calling for at least a 10-year moratorium that will halt development of the industry because there is no way of reconciling marine conservation and deep-sea mining.”

Many are understandably urging caution simply because so little is known about the deepest parts of oceans; any knowledge lost could be lost forever. It is also difficult to know how long the seabed will take to recover from human interference. Belgian firm Global Sea Mineral Resources conducted a small-scale trial in April 2019 in an effort to determine how long it will take for species to repopulate areas cleared for deep-sea mining, but previous studies do not fill environmentalists with much optimism. In 2015, 26 years after a seafloor disturbance experiment was carried out in the Peru Basin of the Pacific Ocean, marine fauna levels remained depressed.

Still, for a balanced discussion to take place, the environmental hazards of deep-sea mining should be compared with the damage caused by land-based mining projects. Mining on land creates large quantities of air pollution, results in landscape destruction, contaminates nearby water sources and damages local biodiversity. These mines are also huge eyesores.

In contrast, the comparative richness of the mineral deposits found on the seafloor means deep-sea mining projects are much more contained than those on land. Initial research indicates that the mineral concentration found in the hydrothermal vents off the coast of Papua New Guinea is at least 10 times higher than in a typical land-based mine. The best-case scenario would mean the environmental damage caused by deep-sea mining projects is confined to a relatively small area.

However, once profits start rolling in, the push to expand deep-sea mining projects may become difficult to resist. At that point, businesses and investors will be queuing up to offer national governments huge financial incentives to grant further mining licences. More worrying still, the ecological impact of deep-sea mining is easy to hide. It is out of sight and perhaps out of mind too.

Contractual concerns

One thing saving the seabed from destruction (for now, at least) is the fact that businesses cannot start mining until they have been authorised to do so. While a number of licences have been granted, many remain exploratory for now and include environmental guidelines within their regulatory framework.

“There are two main paths that allow for the awarding of commercial deep-sea mining contracts,” Parianos told The New Economy. “Firstly, each nation state controls the granting of exploration and mining permits within their own territorial waters. And secondly, within international waters, there is a governing act set up by the United Nations called UNCLOS [the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea]. Most of the nation states have signed and ratified this act.”

Nevertheless, questions have been raised about how these mining contracts are awarded. Many of the small island states located in parts of the world with the greatest potential for deep-sea mining are facing sizable economic pressures – plenty also have relatively large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) compared to their populations. This means the exploration and harvesting of marine resources can go ahead largely unimpeded.

“Mining in deep waters within national jurisdictions, within the EEZ of the coastal state, is the responsibility of the coastal state,” Thompson said. “As some operations are co-funded by nations, there could be conflicts of interest in some cases. Better international governance of the oceans, encompassing mining in both high seas and national waters with a well-designed and enforced network of marine protected areas, would help to protect marine biodiversity across all of the ocean.”

Polymetallic nodule contracts issued by the ISA stipulate that contractors must fund training programmes for citizens from developing states, often connected to marine activities, engineering and other employment initiatives. While this could help local communities retain some of the economic benefits gleaned from deep-sea mining, in the grand scheme of things, it’s a small concession for contractors to pay.

In fact, there are concerns that the particulate plumes that will inevitably be created by the process of mining the ocean floor could interfere with marine life in the waters surrounding small island nations in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans. This could damage the fishing industry, which is currently the only lifeline keeping many of these communities afloat. Rather than solving the economic problems facing small island nations, deep-sea mining may end up creating new ones.

Hell or high water

Deep-sea mining may not have begun yet, but it is right that people are raising their concerns now. So little is known about life at the bottom of the ocean, but the fact that the seafloor has remained largely undisturbed by mankind for millennia means deep-sea life forms are likely to be particularly vulnerable to disruptions.

“One of the biggest concerns surrounding deep-sea mining is the potential knowledge that may never be acquired,” explained Thompson. “Some authors suggest that only 0.0001 percent of the deep seafloor has been extensively sampled. There are huge uncertainties surrounding species diversity and processes relating to the deep sea.”

Ironically, the minerals found underwater may actually be essential if humanity is to successfully transition from a fossil-fuel-based economy to a green one. Many renewable technologies require large amounts of the same metals that deep-sea mining companies have set their sights on: a single wind turbine requires 500kg of nickel, while building an electric vehicle requires triple the amount of copper needed for the average internal-combustion-engine car.

Demand for these minerals is not going to go away. Businesses will get them from somewhere – it is just about choosing the method that causes minimal damage to the planet. Whether they come from a terrestrial mine or the ocean floor will depend largely on economics, but regulators must also stand firm when wads of cash are waved in front of them. The deep sea remains one of the few unspoiled places on Earth; that is surely just as valuable as any amount of copper, nickel or gold.

Types of deep-sea minerals

The rich collection of resources that are found on the ocean floor can generally be placed into three different categories. Each poses its own challenge when it comes to harvesting and is accompanied by distinct environmental risks

Seafloor massive sulphides

Seafloor massive sulphide deposits are predominantly found along tectonic plate boundaries or in areas with high levels of volcanic activity. Seawater seeps into seafloor cracks, dissolving minerals and carrying them back up to the surface, where they form hydrothermal chimneys and other deposits. Harvesting minerals in this form will involve a similar process to open-pit mining on land, with metallic ores crushed and pumped to the ocean surface as a slurry. Because these deposits extend below the seafloor, mining can take place over a relatively small area.

Cobalt-rich crusts

Cobalt-rich crusts form on the surface of hard rock substances at a rate of between one and five millimetres every million years. Around 57 percent of these crusts are believed to reside in the Pacific Ocean, but the mining process is expected to be highly labour-intensive due to the difficulty of removing the crust from the underlying rocks. Despite the length of time they take to form, crusts that are more than 25cm thick have been found. An area south-west of Japan, known as the Prime Crust Zone, is estimated to contain 7.5 billion tonnes of cobalt-rich crusts.

Polymetallic nodules

Polymetallic nodules are perhaps the best known of the seafloor mineral deposits. They are generally between five and 10cm in diameter and are formed by the slow accretion of manganese and iron hydroxides over the course of millions of years. These nodules are causing such excitement in the mining industry because they are simply lying on the seafloor waiting to be collected, often covered by little more than a few centimetres of sediment. Bringing them to the surface in the most economically viable way, however, will require large areas of the seafloor to be mined.