Onkalo aims to solve the 100,000-year problem of nuclear waste storage

Nuclear waste will remain a deadly threat for hundreds of thousands of years. Despite having decades of hazardous waste in temporary storage, the world is only now finalising plans for long-term containment

Sitting deep underground, the hope is that nobody will come upon Onkalo by accident, even thousands of years from now

The disposal of high-level nuclear waste is a problem that should have been solved by now. As the deadly material lurks in temporary storage all over the globe, the first steps towards permanently storing some of it are finally being arranged. But keeping humans away from anything for 100,000 years remains a challenging task.

Current solutions for storing high-level nuclear waste, mostly spent uranium fuel rods no longer useful for generating electricity, are temporary. The rods, still hot, are housed in spent fuel pools. These concrete and steel structures filled with water cool the rods for at least five years before they are moved into dry storage – similar casks, but without the water.

While generally safe, these containers will not survive long enough to house the material for as long as it remains dangerous. The rods’ time in the casks will be a mere blip in the 100,000 years they need to be contained. Thankfully, the world’s first truly long-term solution has finally been set in stone.

Burden of proof

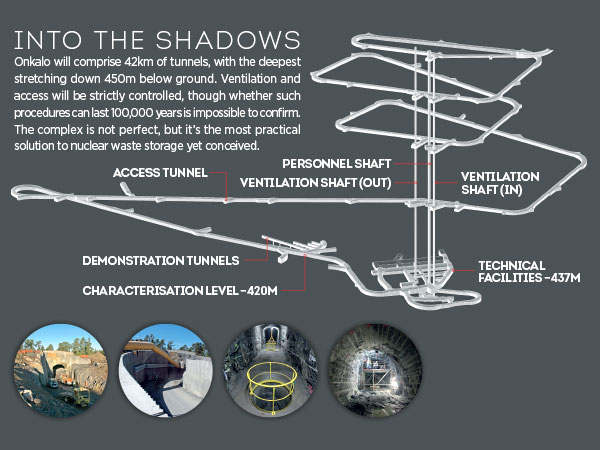

Olkiluoto Island is located off Finland’s west coast, and will house Onkalo, the world’s first truly long-term solution to storing high-level nuclear waste. The hazardous material will be locked in over 42km of tunnels stretching 450m below ground. It is the first step of a project that began in 2004, with a small research station investigating the suitability of local geology. In late 2015, the project received final approval, and the facility will begin taking on waste in 2020. It has space for 100 years’ worth of nuclear waste. While the facility has been criticised by environmental organisations, including Greenpeace, who claim further investigation is needed, the project has been widely accepted as the first real answer to long-term waste storage.

Current solutions for storing high-level nuclear waste, mostly spent uranium fuel rods no longer useful for generating electricity, are temporary

Certainly, Onkalo has made further strides than the equivalent project in the US, Yucca Mountain. Located in the Nevada desert, the similar development was first conceived in 1987. Construction has since been on and off, thanks to the political toxicity of the issue. The most recent barrier to its completion has been the declaration of the Basin and Range National Monument in the path of a planned railway line that would have transported the waste to the facility. What’s more, if the project was ever completed, it would have an even bigger problem: the entirety of the nuclear waste in US temporary storage facilities is now more than the planned total capacity of Yucca Mountain.

Time of the preacher

Beyond the immediate practicalities, perhaps the biggest problem, faced equally by Onkalo and all similar projects, is how to make sure future civilisations don’t irradiate themselves by opening the facility. Since the waste will remain dangerous for 100,000 years, there needs to be a way to communicate the danger of nuclear waste not just to our grandchildren, but to societies in the distant future. These societies may not understand the concept of radiation and, more pertinently, may not be able to comprehend any current languages or the cultural symbols we use to denote danger.

It is a far bigger problem than it may seem. Various academics, from sociologists to philosophers, have been attempting to determine the best way to signpost this danger. In 1990, artist and architect Mike Brill was invited to a panel tasked with solving this problem for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico, which stores low-level nuclear waste. He suggested a landscape of thorn-like concrete spines to instil a sense of dread.

US podcast 99% Invisible lifted the lid on an even more curious solution. In 1981, the Human Interference Task Force, a panel put together for Yucca Mountain, suggested ‘ray cats’. The plan was to genetically modify cats so their fur changed colour when exposed to radiation, and then culturally embed the rule “if your cat changes colour, move far away” by way of tales and folksongs – the idea being that such media tend to retain their meaning and pass through time more fully intact than visual signage.

The perfect solution is yet to be proposed, but there’s still plenty of time. For now, multilanguage warning signs are more than enough. The problem of storage, which Onkalo aims to solve, is a much more pressing matter.

Nuclear waste will be locked in over 42km of tunnels, reaching 450m below ground

The waste at Onkalo will

remain dangerous for a staggering 100,000 years

There needs to be a way to communicate the danger to societies in the distant future

In 1981, cats which change colour near nuclear waste

were suggested as an option

In 1990, artist Mike Brill suggested concrete thorns

to deter people

No solution has yet been agreed, but at least the waste is secure for the moment