HAV Airlander 10 takes to the skies

A British design firm has big plans for its latest project. Out of fashion for 80 years, the airship could be about to rise again

The Airlander 10, partially reassembled in a hangar at RAF Cardington

The hybrid airship Airlander 10 is the world’s largest aircraft. At 92 metres in length, it is 21 metres longer than the best-selling Boeing 747-400 jet airliner. It can carry a payload of 20,000 pounds (or eight large elephants) and can take off from land, water or ice – all while burning a fifth of the fuel of a conventional aeroplane. Already this year, the craft has attracted a £3.4m grant from the UK Government, a €2.5m grant from the EU, and £2.4m in crowdfunding (almost £2m more than its target). It’s also being backed by Iron Maiden frontman Bruce Dickinson.

Though it’s a British baby, and though it’s stirring up interest among European investors, the Airlander 10 began life as a US military project. Back then, it was known by the decidedly more parade ground name of ‘Long Endurance Multi-Intelligence Vehicle’ (or LEMV to its friends). It was hoped the craft would carry out long-term surveillance and reconnaissance of America’s enemies.

Whether it’s a success or not, there’s no doubt the Airlander 10 is an impressive piece of engineering

The US Army invested over $154m in a prototype version created by British design firm Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) and US aerospace company Northrop Grumman (previously responsible for the B-2 stealth bomber). The LEMV made its maiden test flight in New Jersey in 2012. Though a success, the craft fell victim to military spending cuts, and languished unused until HAV bought the prototype for $301,000 in late 2013 and had it reassembled at RAF Cardington in England.

High hopes

Chris Daniels, HAV’s Head of Partnerships and Communications, says: “[The Airlander] was designed for military surveillance, which will continue to be one of its main markets, and that means it is also ideal for civil surveillance applications and for undertaking geo-surveys.” It could also be used for light cargo roles in remote locations (the fact the craft requires minimal infrastructure to operate is a big advantage over aeroplanes) and is, according to Daniels, “particularly good for carrying outsized loads such as wind turbine blades”. HAV hopes it will also be suitable for the traditional airship markets of ‘flightseeing’ and advertising – as Daniels points out, “it makes a very big billboard”.

Mike Durham, Technical Director at HAV, told The Telegraph: “The technological problems with airships that have stopped them ruling the skies have been gradually ticked off.” Daniels adds: “Material technology and computer-aided design have had a significant impact on being able to come up with a design that can robustly achieve this mix of aerodynamic and aerostatic lift.”

The ‘hybrid’ description comes from the fact the Airlander doesn’t gain all its lift from its helium envelope as airships do. Instead, up to 40 percent of it comes from the aerofoil created by its wing-like multi-hull shape, while the vectored thrust of the engines gives additional vertical lift, like a helicopter.

The future

HAV plans to undertake funded demonstrations of the Airlander 10 in the second half of 2016, with the expectation being that commercial operations will begin in 2017 or 2018. The company claims there is a market for over 600 Airlander units. Beyond that, HAV has plans for an even bigger hybrid vehicle: the Airlander 50, boasting a cargo bay of 500 cubic metres. This behemoth will, says Daniels, “address the remote cargo market at a lower operating cost, per tonne-kilometre, than ice roads or bush roads”.

Whether it’s a success or not, there’s no doubt the Airlander 10 is an impressive piece of engineering, and a reminder of the capabilities of a technology we’ve largely abandoned. It’ll be a fascinating thing to study, even if it doesn’t take off.

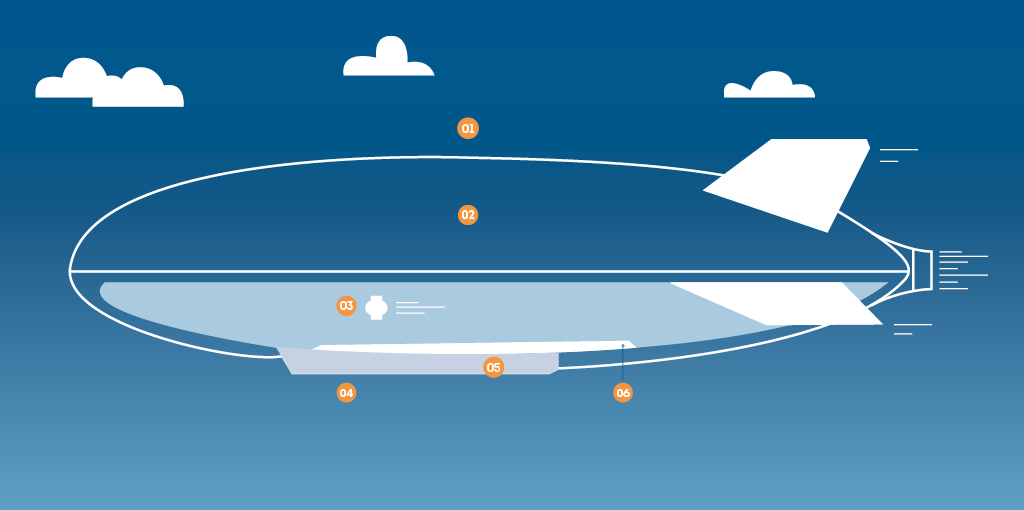

A closer look

The unusual triple-hull design of the Airlander 10 is modelled on a wing and provides up to 40 percent of the vehicle’s lift. The rest comes from the helium-filled envelope inside the body and vectored thrust from its engines.

There is no internal structure; the rigidity comes from the helium envelope and the Vectran material from which the body is made. Vectran is, pound for pound, five times stronger than steel and has been used in bridges, ships and spacecraft.

The four turbocharged diesel engines can be angled to provide vectored thrust for take-off and landing. It’s hoped it will be possible to angle future versions upwards, to work in the same manner as helicopter rotors.

Weight is a major challenge in aircraft design and an area in which important advances have been made since the golden age of airship travel. Carbon composite materials are used throughout to keep the Airlander as light as possible.

The Airlander 10’s internal compartments mean it can be used for light cargo roles in remote areas, while a payload beam on the mid-body allows it to carry external payloads, slung below the main multi-hull body of the vehicle.

The underside of the Airlander is fitted with pneumatic tubes. These allow it to land and move about on the ground, water or ice, and can be ‘sucked in’ during flight to improve the ship’s aerodynamic profile.