Shale gas extraction explained

Many believe the US is on the brink of a new industrial age, as it benefits from a recent energy boom. Here we look at the major components of hydraulic fracturing, its environmental implications, and its impact on the US and global economies

Hydraulic fracturing has spurred economic growth in many countries, including the US, but it is also a subject of some content - with critics concerned about its effects on the environment

It’s no secret the prospect of diminishing energy supplies is high on the agendas of various national powers. That was until recently, when the introduction of hydraulic fracturing saw unprecedented gains in the energy sector. The US in particular has benefited from a so-called shale revolution, with its daily production of crude oil increasing from five million to 7.5 million barrels between 2005 and 2013. The country also had its largest production increase on record in 2012, and many believe the superpower’s daily capacity could reach as much as 11m barrels by 2020 – better even than Saudi Arabia. What’s more, the US now ranks as the world’s largest producer of natural gas, and the country’s production rate has soared some 20 percent in the past five years alone.

[T]he full impact of shale extraction will most likely take years to be fully comprehended

US energy independence

Owing to the simple dynamic of supply and demand, the price of oil and gas has fallen significantly since the onset of shale drilling. From 2008 until now, the price of natural gas has plummeted approximately 75 percent, offering an indication of the rate at which the technology is sparking change. The drop has been welcomed by consumers and businesses alike, which are enjoying cheaper goods and wider margins at an ideal time, given the ongoing effects of the financial crisis.

The rate at which the US’ oil and gas production is gaining has brought an end to the country’s longstanding reliance on nations as far afield as the Middle East. Some have even grown so confident as to suggest the US’ emboldened productivity and prices could usher in a new era of economic dominance. While US production is still short of demand at the present, if the country’s production rate continues to gain at the same pace, energy independence could be possible in the not-too-distant future.

In response to the price advantages that come with increased production, numerous companies have opted to return their operations to US soil – otherwise known as ‘reshoring’. The movement applies to all manner of enterprises, although the vast majority of them are in manufacturing (lending further credence to the possibility of a new industrial age). The fracking boom is also anticipated to bring as many as two million new jobs to US shores by 2020. In states such as North Dakota, where there are vast shale oil and gas deposits, unemployment has already fallen to as little as three percent.

Global interest

The shale revolution is far from confined to the US, however, with countries as far afield as China, Argentina and Russia also playing host to huge reserves of shale oil and gas. If these countries proceed to take up fracking in much the same way as the US has done, an overdependence on Middle Eastern reserves will diminish and global prices will fall. Provided countries across the globe implement fracking technology and extract their untapped shale reserves, global gas production could rise by as much as 50 percent by 2035.

The process of fracking is not without its share of controversy, however. The most notable bone of contention is the slump in renewable investment that has accompanied the boom. Many believe fracking is sorely under-regulated and that its environmental impact is still poorly understood.

However, the full impact of shale extraction will most likely take years to be fully comprehended, and many of the keenest criticisms today amount to mere speculation. What is certain is that fracking has far less of an impact on the environment than coal, and many see it as a low-carbon alternative.

Dig a little deeper

Shale gas extraction explained

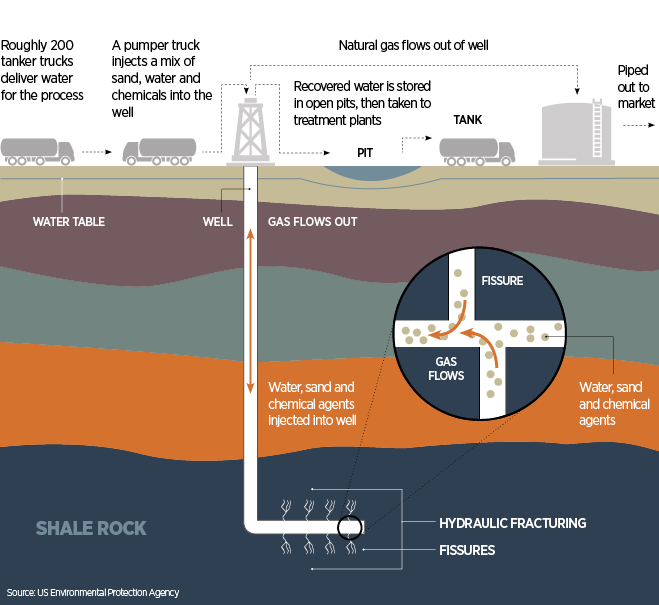

Hydraulic fracturing, known as ‘fracking’ is where more than a million gallons of fluid is injected into rock formations to stimulate the flow of natural gas or oil. This fractures the rock and increases the volumes of gas or oil that can be recovered above ground.

The fluid used in hydraulic fracturing commonly consists of water, proppant and chemical additives that open and enlarge fractures within the rock formation. Each company uses a different mixture of chemicals and works to protect its secret formula.

The chemically induced fractures can extend several hundred feet away from the wellbore. The proppants, which consist of sand, and ceramic pellets or other small particles, fill the cracks caused by the liquid and keep the newly created fractures open.

Once the injection process is completed, the internal pressure of the rock formation causes fluid to return to the surface. This fluid can contain injected chemicals as well as natural materials such as

brines, metals, radionuclides and hydrocarbons.

Wells are drilled vertically and can extend to hundreds and thousands of feet below the land surface. The drilling may also include horizontal or directional sections, extending thousands of feet on their own, to maximise the amount of natural gas and oil collected.

The full impact of shale extraction is not yet known and will likely take years to calculate, but many are concerned about its environmental impact. In 2013, 1,000 people gathered in Manchester for largest ever fracking protest.