Sharks are attacking the internet

Just when Google thought it was safe to enter the water to lay its giant internet cable between the US and Japan, it discovered it must contend with the ocean’s top predator

As Google expands its presence by building a series of fibre optic submarine cables, it is trying hard to prevent sharks from destroying them

For many, the internet is what pours out of their Wi-Fi router, allowing them to access the World Wide Web so they can laugh out load at cat pictures, stream the next big Netflix original, or get frustrated at being destroyed yet again by some random 12-year-old in the latest instalment of Call of Duty. But to do all this requires a vast physical network of cables that provides the backbone of the internet’s infrastructure; one that crosses oceans and connects continents.

Modern fibre optic submarine cables are the foundations of this information superhighway. They are installed along the seabed, linked together by an array of land-based stations, which send digital traffic to their designated destinations. Fitting these submarine cables is a big undertaking both logistically and financially, not least because of the risk of damage to the cables – both accidental and deliberate. But now Google, which is investing over $300m to build a trans-Pacific network that will connect the California coastline with the Japanese cities of Chikura and Shima, has to take out an insurance plan against shark attacks.

Taking a chunk out

Underwater surveillance footage has shown a shark tucking into a submarine cable similar to the one Google plans to install, leading the tech-giant to go to great lengths to protect its new project. Dan Belcher, a product manager on the Google Cloud team, explained how a Kevlar-like coating will encase the fragile glass fibres and prevent them breaking under the pressure of a bite. Sharks possess a sixth sense that enables them to detect electromagnetic fields: scientists believe it helps the fish navigate and track prey. It would explain why the sharks have an appetite for these cables, which they may mistake for floundering fish.

Despite the recent YouTube clip showing Jaws now has a taste for terabytes, the International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), which is responsible for providing guidance on issues related to submarine cable security, says cable damage from such attacks is rare. The ICPC released a statement explaining that the first recorded shark bites of a deep ocean fibre-optic cable occurred off the Canary Islands in 1985, but three independent studies of databases show a marked decline in the number of faults caused by fish bites, including those of sharks. The latest analysis, covering 2008 to 2013, recorded no cable faults attributed to sharks.

Relieving the pressure

Google plans to have its cable system, which has been aptly named FASTER, fully functional by June 2016. The network is aimed at relieving some of the pressure on the existing infrastructure: pressure that has been created by the rise in smartphone usage. Google is not alone in the FASTER project, having joined forces with big players in the Asian telecoms market, including China Mobile International, China Telecom Global, Global Transit, KDDDI and SingTel.

“At Google we want our products to be fast and reliable, and that requires a great network infrastructure, whether it’s for the more-than-a-billion Android users or developers building products on Google Cloud Platform. And sometimes the fastest path requires going through an ocean,” said Google’s Senior Vice President of Technical Infrastructure and Google Fellow, Urs Hölzle. “That’s why we’re investing in FASTER, a new undersea cable that will connect major West Coast cities in the US to two coastal locations in Japan with a design capacity of 60 TBPS (that’s about 10 million times faster than your cable modem).”

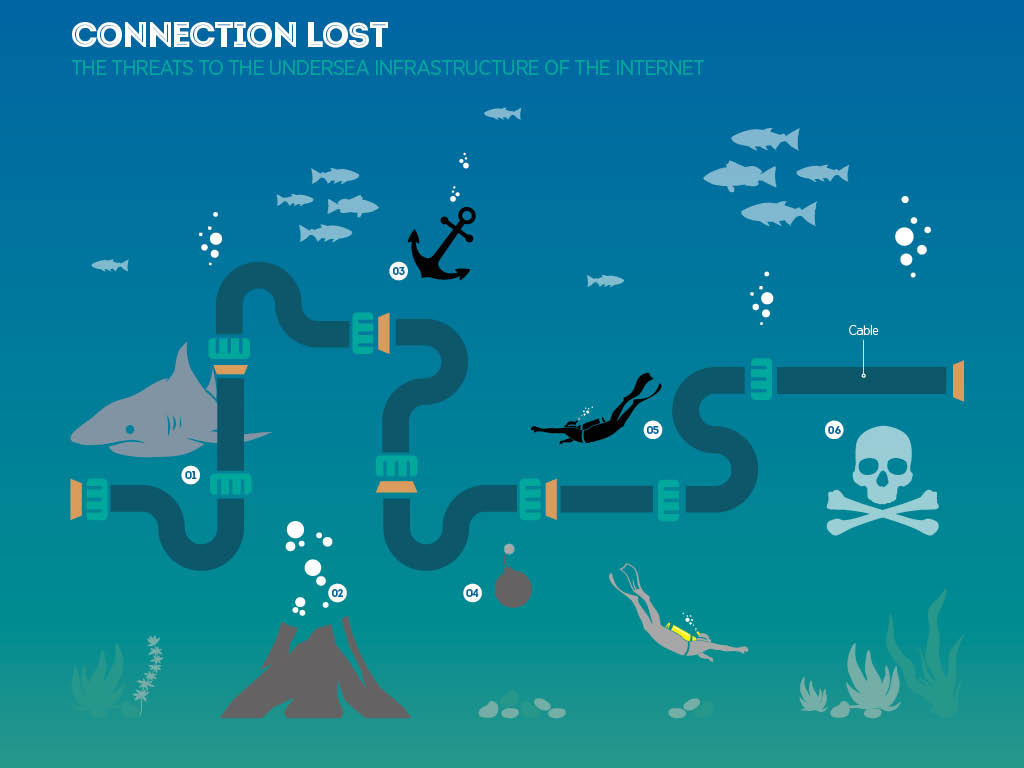

Sharks have been known to bite into undersea cables, apparently in the mistaken belief they are struggling fish. Kevlar coating protects the delicate glass fibres in modern cables against such attacks.

Undersea volcanoes are a concern off the Horn of Africa, where a number of cables converge as they pass from the Red Sea into the Gulf of Aden. An eruption could disrupt connectivity to a large part of Asia.

It is often difficult to determine the cause of damage to undersea cables. Ships’ anchors dragging across the seabed are believed to have been behind one major outage near Alexandria in 2008.

Sami al-Murshed from the International Telecommunication Union suggested the 2008 disruption could have been an act of sabotage. Such infrastructure would be an obvious target.

In 2013, the Egyptian Navy arrested three scuba divers they claimed had been attempting to cut the SEA-ME-WE 4 cable that stretches from Singapore to France. It is unclear what motives the men may have had.

Vietnamese pirates removed a section of undersea cable in 2007 in the mistaken belief it contained copper. Two years later, naval vessels were deployed to protect a ship laying cables off the coast of Somalia.