A higher minimum wage benefits all parties – employers need to look at the figures

Higher minimum wage levels are viewed with caution by shareholders and investors, but they could actually provide a financial boost

A fairer minimum wage benefits both employers and employees, with shareholders ultimately profiting too

The US’ low-wage economy is best characterised by one or both of two extremes: on the one end, we have unskilled workers whose pay scarcely covers the basic costs of living; on the other, we have a corporate class overcome by record-breaking profits. Over the past couple of years, this disparity has become a mainstay of policy discussion, and the issue of inequality itself has featured prominently in the national debate.

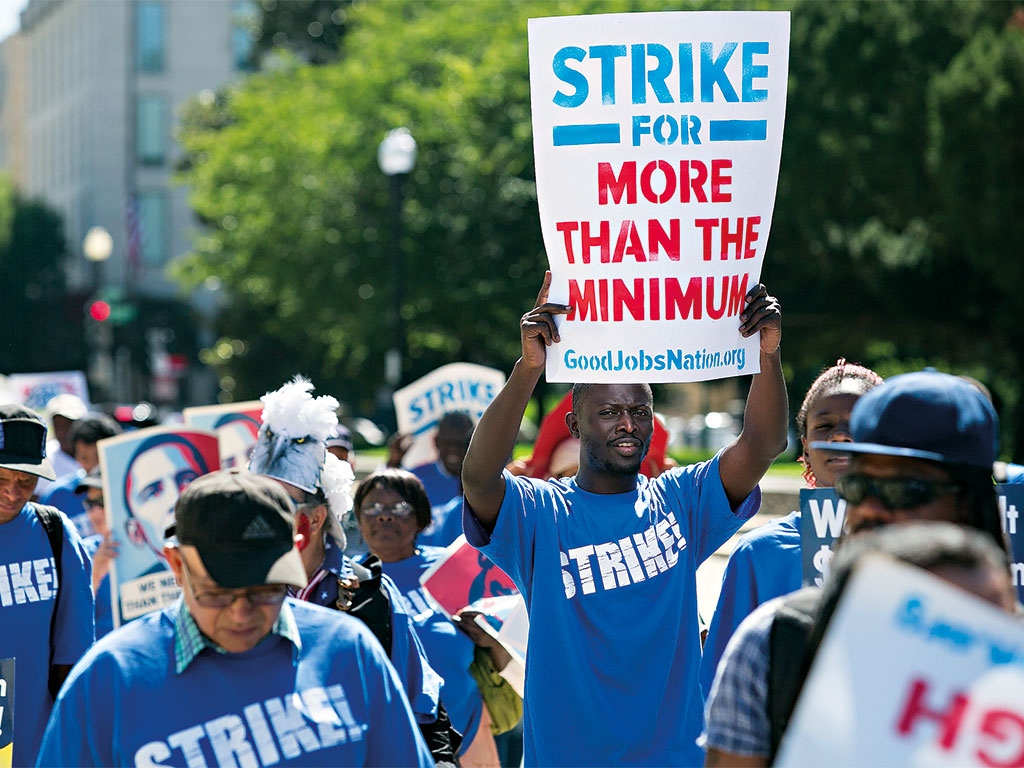

Substandard wages have turned workers into activists – the ‘Fight for $15’ campaign having produced results, even if the desired outcome is being phased in only gradually – while those writing on the subject of income inequality have elbowed their way into the bestseller lists. Any politician with a harsh word to say on inequality is guaranteed votes, while worker pay and unemployment arguably have more sway over public opinion than any other two issues combined.

Research out of UC Berkeley’s Labour Centre last year estimated over half of all America’s fast food workers collected some form of public assistance on top of their wages – costing state and federal governments $7bn a year. But as costly as these ultra-low wages are, governments are concerned anything higher could prove an annoyance for corporations. Both sides, it seems, are at a loss as to how best right the imbalance, and this quandary has given rise to a climate of hostility.

Low numbers, low pay

In the meantime, companies’ profits have been boosted to never-seen-before heights, employing as small a number of workers as possible and at as low a rate as they can muster. On the face of it, it seems corporations are among a minority of parties not affected by widening inequality, and calls for a higher minimum wage have often been overturned by the threat of job losses, higher consumer prices and uncertainties with regards to what constitutes the ‘living wage’.

Research out of UC Berkeley’s Labour Centre last year estimated over half of all America’s fast food workers collected some form of public assistance on top of their wages

For these reasons and others, not much has changed: cash piles, both in dollar terms and as a share of the economy, are stratospheric, though calls to raise pay for those on the lowest rungs of the ladder are finally beginning to make an impact, with the average hourly wage in the US having risen 16 percent since 2008.

Today more than ever, the plight of the entry-level worker is known to all but a few in corporate America, and changes like the McDonald’s $10-an-hour minimum wage are symptomatic of a new, arguably more progressive corporate culture. Many of the nation’s top employers have opted for a starting pay above the federal minimum, while 29 states have an hourly minimum above the $7.25 federal rate.

Those with a financial stake in these companies are beginning to wonder what rising worker wages might mean for corporate balance sheets. Those caught up in the debate could find themselves with a delicate balancing act to strike between worker demands and investor confidence, as higher wages, many fear, could tighten the vice on corporate profits.

Paradoxical situation

Illogical as it may seem, the companies that stand to gain the most business from a higher minimum wage – namely McDonald’s, Walmart and the like – are the most anxious about its effects on profitability. The former said in its last annual report: “The trend towards higher wages and social expenses could have a negative impact on the margins of our company-owned restaurants.” Considering the lack of research to show this or otherwise, the hesitancy is entirely understandable. GAM Multi-Asset Class Solutions (MACS) remarked in an investor note last year that, while a great deal has been said about the relationship between the minimum wage and unemployment, much less has been written and researched about its correlation with profitability.

“While the minimum wage is an emotive issue central to the equality debate, it is important for investors to coolly assess how it will affect corporate profitability and, ultimately, the course of equity markets”, wrote Julian Howard and Graham Wainer, both of MACS, in the note. “It remains the case that – whether the result of politics or labour market conditions – higher ‘forced’ wages are likely to negatively impact the profit outlooks of firms relying on low-wage workers and whose customers don’t consume significantly more of their product as they get wealthier.”

In the months after Walmart raised wages for half a million American workers, the company revealed its profits had taken a hit: having lifted its starting wage to $9 last year, and again to $10 more recently, the US’ largest private employer scaled back its profit outlook for the year. And while sales in the second fiscal quarter racked up a fourth successive quarter of comparable growth, the uptick was not enough to cushion the knock-on effect for its bottom line.

A decline in customer satisfaction and issues to do mostly with staffing prompted the retail giant to introduce a higher minimum wage on the basis that doing so would improve customer service and its reputation among consumers. The fear for lower earners, however, is that much of the focus in the upper echelons will fall not on rising sales, but on falling profits, confirming worker and investor interests do not necessarily align.

Granted, a US comparable sales increase of 1.5 percent beat Wall Street expectations. However, Walmart’s profit of $4.40 to $4.70 per share last fiscal year was down from an earlier range of $4.70 to $5.05. Not just Walmart but McDonald’s, Starbucks, IKEA and Gap have all boosted pay or put in place a more generous minimum recently. That said, they have also raised prices or cut jobs to stave off the short-term effects on their bottom lines.

“Somewhere along the line, we’ve got to reflect those increased costs and increase the revenue”, said Michael Weinstein, CEO of Arks Restaurants, in an earnings conference call last year. “If you’re a purveyor selling us chicken, and if your minimum wages go up, you’re going to raise your prices to us, and we’re going to raise our prices to the customers.”

Clearly, employee pay and benefits is the largest cost for many employers. Katie Donovan, Founder of Equal Pay Negotiations, cited Human Capital Management Institute figures that said the two outlays average around 70 percent of expenses for employers. She told World Finance: “If the percentage of lower earners for one employer is large enough then higher wages can indeed impact corporate profits.”

Up on high

Donovan and others maintain, however, that higher worker wages could actually benefit shareholders seeking higher returns, despite the fact the two groups are often at odds with one another. While fast food workers in 190 US cities walked off the job last year to contest low wages, with their attention mostly directed at McDonald’s, the fast food chain later announced it would pay out a – seemingly disproportionate – $30bn in dividends to shareholders. Former prospective Democratic presidential nominee Bernie Sanders said of the situation: “In America today, what we are seeing is the richest people becoming richer, and almost everybody else becoming poorer.”

“I’d say shareholders support what helps a company grow because it is growth that ultimately makes shareholders wealthy”, said Donovan. “In theory it’s great to keep costs down, but at some point low salaries will keep top talent away from an employer. Good employees are key to growth and, currently, to get good employees, employers need to pay higher than they have been for the past few years.”

In spite of examples that show higher wages can drive growth in the long term, the prevailing logic among major employers is the same as that held by the likes of Weinstein, who figure the issue is a zero sum game. Charts detailing the supposed impact of higher wages on profitability vary, but the overriding message is that treating employees with more respect means they will show the same respect to customers. The question is how much it will have that effect, which in turn will dictate whether or not employers take the plunge.

For as long as they hold fast to the thinking that employees simply do not add enough value to merit a wage hike, the uneasy relationship between workers and investors will remain.