Women’s empowerment: Bridging the gender divide

As the inequality gap endures in many boardrooms around the world, the debate turns once again to inequalities in the workplace

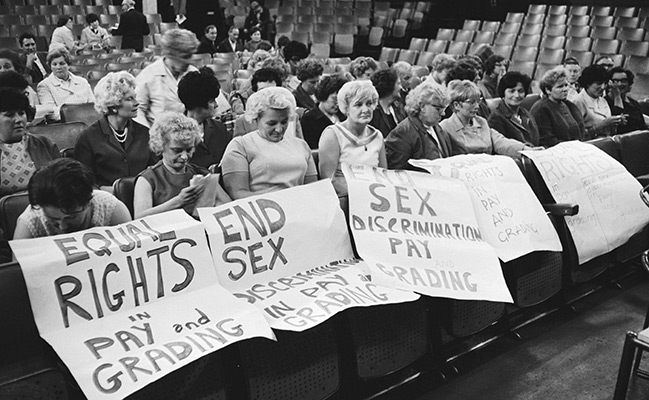

In June 1968, the Ford sewing machinists strike hit the UK. On that occasion, the women employed by the car manufacturer to stitch car seats and linings at its Dagenham plant went on a three-week strike, demanding to be paid the same as their male colleagues. They succeeded in winning a pay rise, though they wouldn’t be granted equal wages for another 16 years.

Many parts of the world have followed suit with similar reforms, and today women make up around 40 percent of the global workforce. Over 40 years after the Dagenham strike, it would be easy to dismiss issues such as equal pay and the glass ceiling as things of the past, but they are not. Women account for almost half of all jobs worldwide, but are not accordingly represented at the top.

Women account for almost half of all jobs worldwide, but are not accordingly represented at the top

The 2010 Female FTSE Report shows that women occupy only around 12.5 percent of board seats and 5.5 percent of executive directorships in the UK. It seems a contradiction that, after early victories in the 1970s and 1980s, women still struggle to make it to the top today. Women continue to earn less than men in every job step along the way. In the UK, women earn an average of 10 percent less than a man would in an equivalent position.

The disparities reflect society’s behaviour towards women, equality and business. Though attitudes vary from country to country and industry to industry, women continue to be underrepresented across the board. The World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index is a good barometer with which to gauge how these attitudes filter down into the everyday lives of women in the workplace.

Saadia Zahidi, Senior Director and Head of Constituents at the World Economic Forum, explains that the yearly rankings are a good way for countries to track their development in the areas of women’s health, education, economic participation and political empowerment. She said: “We are trying to see how well countries are distributing resources and opportunities between women and men, regardless of whether these are rich countries or poor countries and whether they have high levels of resources or low levels.”

A question of competition

The Gender Gap Index lets us look objectively at the value a society gives to the female half of its population. The reasoning is that the more a country invests in health and education for women, the more access they will have to achieve economic participation and political empowerment. For Zahidi, having women actively participating in the labour market and in politics is not just fair, it’s good maths.

Zahidi said: “Women make up 50 percent of the population of any given country: that’s 50 percent of the human capital available to any country. If that human capital is not invested in – is not educated, is not healthy – countries are going to lose out in terms of their long-term competitive potential. Governments and businesses need to be collaborating to ensure that the right kind of environment is provided for women to be economically integrated. In many cases, that means being able to balance work and family, in other places it means access to finance or to childcare structures.”

The issue is greater than one of participation

The Gender Gap Index included 135 countries this year. Iceland and Scandinavian countries came out at the top: Chad, Pakistan and Yemen were at the bottom. Zahidi highlights the relationship between countries that have little or no gender disparity and their ability to compete in the global market.

Zahidi said: “Six out of the top 10 performing countries in the Global Competitiveness Index are also among the top 20 in the Gender Gap Index, so there is a strong correlation. Countries towards the top of the rankings have one half of their human capital being used in a far more efficient way than other countries.”

Despite the evidence, no country has yet managed to close the gender gap completely. Iceland, the leader on the World Economic Forum Index, is still 14 percentage points away from a perfect score. Yemen, at the bottom, is 99.8 percentage points away from achieving gender equality. Zahidi said: “Countries towards the bottom of the ranking have not made the investment in terms of health and education, and consequently have not seen the results in terms of economic participation and political empowerment.”

The arguments for increasing competitiveness and efficiency make sense, but the gender gap endures. Secretary General of the Council of Women World Leaders, Laura Liswood said: “it is a combination of the efficiency argument, which is that ‘your economies will be more efficient [if more women are better qualified and entering the labour market]’ and then you have the equity market: it is just fair.”

Boardroom politics

The fact remains that women are still underrepresented in the boardroom and upper management – even in countries that score highly on the Gender Gap Index, like Sweden. It is this entrenchment of discriminatory attitudes that has led countries to debate imposing mandatory quotas for women in upper management and many private companies worldwide to adopt such measures.

Gail Kelly, CEO of Australia’s Westpac Bank and the country’s highest-paid female executive, has made no secret of her goal to promote women into 40 percent of the bank’s upper management roles. In the UK, a group of CEOs have banded together to publicly pledge their commitment to raise the number of women on boards from an average of 12.5 percent to 30 percent. The aptly named 30 Percent Club counts among its members CEOs from Lloyds Banking, Centrica, KPMG and Deloitte.

Norway has led the way in making positive discrimination the law. In 2002, Economy Minister Ansgar Gabrielsen announced a 40 percent gender quota to fill the seats in the boards of market-listed companies. At first, business representatives reacted badly, speculating that foreign investors would flee the country and the stockmarket would crash, but an overwhelming majority in parliament voted the quota system in.

10 years later, Norway is the second highest-ranking country in the World Economic Forum Gender Gap Index. Liv Monica Stubjolt, a Norwegian business lawyer who has served as state secretary in the foreign and energy ministries, argues the quota system has had a positive effect on the way women perceive their career choices. She said: “The quota has had the effect that women also now feel like they are seen as candidates for executive management positions.”

With the European Commission set to start another round of debates about quotas, it seems Norway’s system is quickly becoming the favoured policy with which to tackle the gender gap in business. However, this has not been enough to convince opponents of the quota system who claim the law has caused a drop in profits and share-prices. They attribute the drops to the inexperience of the newly appointed boards. Jacob Hiim of the Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise argues that the quota system is an “attack on companies’ right to self-determination”.

Quota systems certainly push women into higher-ranking positions, but not everybody agrees that this positive discrimination alters the fundamental structure of the labour market. CEO of AGI, Elizabeth Corley, has declared herself “against quotas”. She said: “It should be a last resort when we have failure. Every woman or minority would be looked at in the wrong way.”

Indeed, when quota systems are adopted, there is a negative perception of women. The presumption seems to be they are only sitting in that boardroom or in that upper management position because a quota needed to be filled: rather than because she was the most qualified person for the job. CEO of Burberry, Angela Ahrendts said: “Whether it’s countries or companies, it’s about putting the best person in the job who can unite people and create value. A man could do this job just as well as I can.”

Britain’s Minister for Women and Equalities Maria Miller also agrees that quotas can be “dreadful”, and that a preferable approach would be to incentivise promotions based on removing barriers rather than forcing political correctness. Though Italy, Spain and other European countries have followed in Norway’s steps, countries like Britain have opted to tackle the issue through policy.

Women’s rights

Countries around the middle of the Gender Gap Index have made significant investments, but have failed to remove barriers preventing women participating more actively in the economy. Zahidi said: “Countries such as Japan or countries in the Arab world that have made investments in women’s health and education but then haven’t removed the barrier to women’s economic participation and political empowerment and are essentially not reaping the rewards of their initial investment.”

Policy change is fundamental to support women in their decisions to join the labour market, and more importantly, to be able to reconcile their work responsibilities with their family and maternity duties. Nordic countries towards the top of the Gender Gap Index have sophisticated parental leave, which does not force mothers to choose between having children and climbing the career ladder.

In Sweden, both parents receive 480 days of leave per child, much of which is transferable between parents. This flexible system encourages mothers and father to divvy up parental responsibilities, and encourages a break from traditional gender roles. The system actively encourages fathers to take more time off and women to return to work sooner by reducing the paid leave by two months if only the mother takes time off work.

Such policies are imperative to change the perceptions towards women in the workplace. Maternity leave is still a big issue, as companies fear they might lose invaluable executives for long periods of time as women go on maternity leave. But as men are encouraged to assume equal parenting duties, the pressure on women is alleviated.

Parental leave is not the only social policy that would enable women to continue advancing their careers. It is the much broader debate around reproductive rights that is often sidelined. In order for women to be able to progress in their chosen careers, it is imperative that they are able to choose when and if they decide to get pregnant. If unplanned pregnancies occur, they must be allowed to decide what course of action to take and be free to have terminations.

If women are not in charge of their reproductive rights, as has been widely debated in the US recently, they become liabilities to the companies employing them. This can foster discrimination against women of childbearing age in the labour market. Discrimination can entail being held back from top positions, but it can also mean women working in top positions earn up to 30 percent less than men.

American activist Joy Lawson said: “We’d all like to think, in 2012, that pay discrimination is a thing of the past, but the pay gap still exists and it’s big: women earn an average of 77 cents on a man’s dollar.” A recent survey by the Chartered Management Institute in Britain has revealed that women executives earn on average £10,060 a year less than their male peers.

The institute’s chief executive, Ann Francke said: “A lot of businesses have been focused on getting more women on boards, but we’ve still got a lot to do on equal pay and equal representation in top executive roles. Twice as many female directors were made redundant compared to male directors, so at that level in the organisation it suggests that this is not all about childcare.”

Slow progress

Research suggests the pay gap can be attributed, at least in part, to career choices made by women, rather than outright discrimination in favour of male employees. For instance, American economist Diana Furchtgott-Roth suggests in her book about the economic progress of women, Women’s Figures, that women often work fewer hours than men, and that they are more likely to take up part time employments.

However, to attribute the pay gap to choices made by women does not excuse the social conditions that limit these choices. Once again, policy and legislation play a significant role and can be useful tools, when employed properly, to close the pay gap and encourage more women to pursue successful careers.

In Britain, 44 percent of all board appointments in the past six months have been women. Progress is being made, however slowly. For the gender gap to be effectively closed in the business world, it will take a combination of policy change, legislation and a cultural shift including both employers and employees – and such shifts can take time.

Zahidi said: “That progress is taking place very slowly. [In the Gender Gap Index] only six countries have improved by over 10 percentage points. And almost 75 countries have improved by less than five percent. So the progress is very slow, even though we are seeing a trend in the positive direction.”

The New Economy recently announced its Women’s Empowerment Corporate Leadership Awards 2012.