How do you like me Nao? Robots come to take Japanese jobs

Japan could soon launch a robot revolution, and, in doing so, relieve some of the pressure weighing down on its shrinking labour force

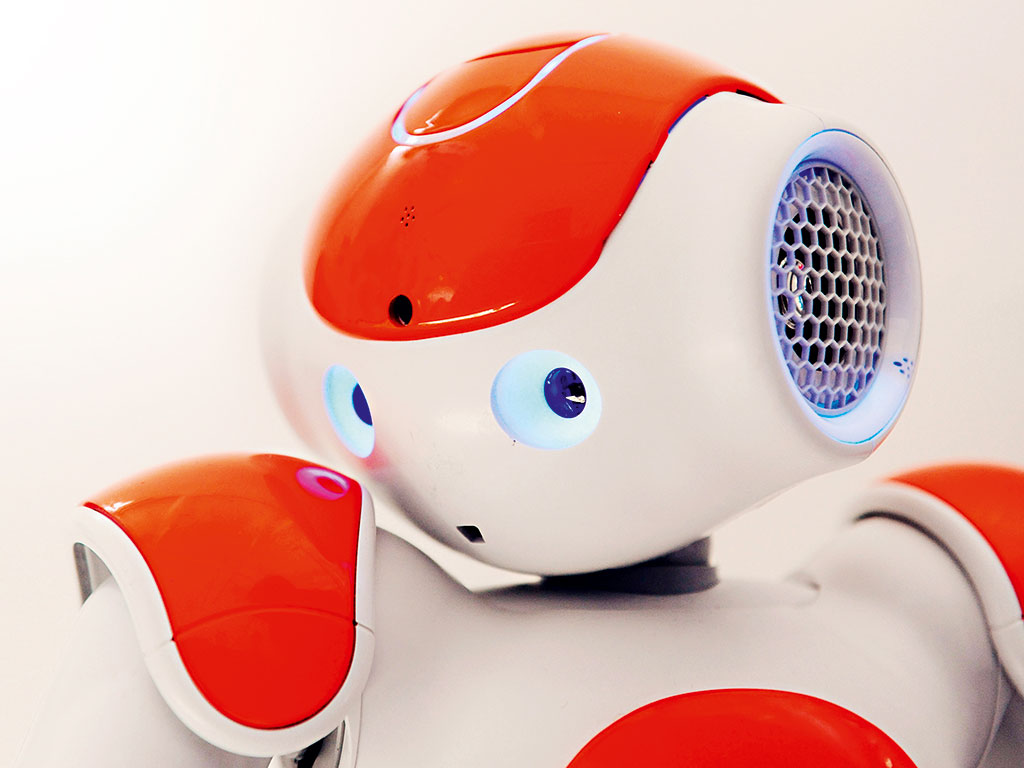

Nao is a robot teller, designed to help non-Japanese-speaking customers. Japan's labour shortage is threatening its economy, but robots could provide the solution

On its opening day earlier this year, the Nagasaki-based Henn-Na Hotel was fronted by 10 almost-identical attendants, each fluent in several languages and contracted to work a 168-hour week. One of the 10 “has been improved in her astonishing appearance and high performance and is now even cuter than her older sister”, while another “is capable of creating exotic facial expressions”. That’s according to the Japanese robotics company Kokoro.

This so-called ‘robot hotel’, with its small staff of androids, has ambitions to have over 90 percent of its services operated by similar machines. While it might be unusual, the case of Henn-Na Hotel feeds into a common discussion about the role of robotics in Japan’s growth story.

Historically speaking, robots have played a larger role in the country than in any other. Over the years, the government has gifted hundreds of millions of dollars in handouts to the robotics industry, in the hope that it might boost productivity. Statistics compiled by the International Federation of Robotics show 40 percent of Japan’s robot population (or 300,000) are hard at work, largely in industrialised jobs. However, with the country’s human population having fallen 268,000 in only the last year, without something much larger – something akin to a robot revolution perhaps – Japan’s labour shortage could spell trouble for its stop-start economy.

48%

Of Japan’s robots fulfil industrial roles

268k

Fall in Japan’s population, 2014-15

$7.5bn

Defence robotics market, 2018

$37bn

Industrial robotics market, 2018

Demographic crisis

According to the country’s Labour, Health and Welfare Ministry, the estimated number of newborns last year clocked in at just over one million, making it the fourth consecutive year in which the figure has fallen to an all-time low. Sources also say that, allowing for local revisions, the figure could fall below the one million mark – and all in a time when deaths have exceeded one million every year since 2002.

Not long ago, the government warned Japan’s population could shrink from 127 million to 87 million before 2060, with 40 percent aged 65 or older, should the situation continue to unravel. More than three years on and the Japanese are still reluctant to welcome immigrants, who make up less than two percent of the population, and the country’s fertility rate is among the lowest worldwide. What’s more, with its workforce on course to shrink a further 16 percent before 2030, Japan’s economy may well be without the manpower to make a measurable impact on its debts.

The issue has blighted outer-lying regions already, with many small towns either underpopulated or occupied only by elderly residents. Elsewhere, the obstacles standing in the way of female participation remain very much intact, as is negative sentiment to unmarried cohabitation and children born outside marriage.

Conventional wisdom holds Japan’s enduring conservatism, chronic worker shortage and ageing population will invite greater deflationary pressures on a country that has only recently escaped collapsing prices. Studies from Tokyo’s Waseda University show an ageing population has pushed consumer prices down 0.6 percent every year for the past 40. And with economic stagnation having already had a hand in reducing population growth, the country must take action – and quickly – to meet its growing demographic challenges.

It is with these issues front and centre that the government last year called for a “robot revolution” to reignite Japan’s fire.

Robot revolution

“This robot revolution will help to solve problems with the declining birth rate, ageing society, services and nursing care, and in agriculture, construction and infrastructure maintenance, and more”, says Gudrun Litzenberger, General Secretary of the International Federation of Robotics. “The utilisation of robot technologies will further improve Japan’s productivity, enhance companies’ earning power, and raise wages.”

The inaugural meeting of the Robot Revolution Initiative Council this year saw Prime Minister Shinzo Abe take to the stage and call on companies to “spread the use of robotics from large-scale factories to every corner of our economy and society”. Received positively by the country (inasmuch as the sentiment was subscribed to by 200 leading companies and universities), the five-year drive, if successful, will see robotics sales reach JPY 2.4trn ($19.6bn) by 2020, up from JPY 600bn ($4.9bn) currently. Kodomoroid reads the latest news bulletins, Telenoid hands out hugs, and Twendy-One conducts household chores. But all these could soon pale into insignificance should Japan’s robot revolution take hold.

In manufacturing, in construction and in the service sector, robotics could relinquish some of the pressure weighing on the country’s overstretched labour force – that is if the Robot Revolution Initiative Council can boost cooperation with the private sector. “The largest number of industrial robots is operating in the factories of Japan”, says Litzenberger. “Japan is the predominant robot manufacturing country and more than 50 percent of the global supply of industrial robots [is] produced by Japanese companies. Even robots are assembled by robots.” This commitment to robotics has only been set out in an official capacity recently, but that isn’t to say Japan’s robot obsession is anything close to a recent phenomenon.

In the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation sits the 10-year-old automaton ASIMO: as clear an indication as any that the country has long stood at the cutting edge of robotics. On the international stage there is no other country more infatuated with robotics than it, and since the 1950s robots have been part and parcel of the national psyche. Some researchers have even speculated robotic pets could replace the real deal within the decade, and reports earlier this year showed owners of Sony’s discontinued Aibo dog were holding funerals for their retired companions. Even Abe joined the love-in last year when he campaigned for a Robot Olympics to coincide with Tokyo’s own.

Buoyed by widespread support, generous government incentives and favourable demographic trends, the rise of the machines over the past half-century has been almost wholly without opposition. However, only in recent years has robotics come to be seen as a viable solution to the country’s demographic crisis.

New competitiveness

Central to Japan’s robotics push is a burning ambition to hold onto the country’s undisputed lead in robotics, particularly as rival nations nearby and further afield threaten to dislodge its place at the front. With its competitiveness fading and companies elsewhere catching up fast, Japanese firms have taken great strides to underline their superiority.

Tokyo-based SoftBank, for example, last year unveiled Pepper: a cloud-based AI it claims can read human emotions. “People describe others as being robots because they have no emotions, no heart”, said the company’s Chief Executive Masayoshi Son at Pepper’s unveiling. “For the first time in human history, we’re giving a robot a heart, emotions.” Beyond that, the company’s calculations show Pepper is equivalent to three human workers in terms of productivity, taking into account the reduced cost of labour and ability to work round the clock. Should SoftBank’s wide-eyed, all-purpose workers strike a chord with consumers, they could play a key role in the coming five years, throughout which the government plans to increase the use of robots 20-fold.

Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, meanwhile, recently unveiled Nao, a pint-sized robot bank teller introduced to serve non-Japanese-speaking customers in branch. Measuring 58-centimetres in height and accomplished in 19 languages, the intention is for Nao to enter widespread use before the Tokyo Olympics in 2020.

The hope for models such as Pepper, Nao and a string of others is that they might inject a shot of productivity into Japan’s inefficient service sector, which, according to METI, is only 60 percent as productive as the US. Presented as a near perfect solution to Japan’s chronic labour shortage, the fear – not necessarily for Japan but in rival developed countries – is that these robo-workers could take much-needed jobs away from their out-dated human counterparts.

Ahead of the fear that robotics could leave millions jobless, however, is the concern that Japan could soon lose its distinction as the go-to home of all things robotics. For decades, no other country has encroached on its dominance, yet studies show it enjoys no such comfort in the present climate. The government is keeping a close eye on neighbouring China, which, as of 2014, was home to 530 robotics companies and occupied a 13 percent share of the market, up from four percent in 2012, while South Korea and the US have also unsettled policymakers. While still accountable for over half of all industrial robotics and 90 percent of parts, developments on foreign soil could upset the country’s dominance elsewhere.

Foreign threat

As a long-time leader in military robotics, the US last year had over 11,000 unmanned aerial vehicles and another 12,000 ground robots to its name, under the assumption that the key to modern warfare lies not with man but machine. Generous defence budgets of days past have given rise to an army of robots beyond that of any other nation, despite China’s fast-growing military prowess having chipped away at the country’s technological superiority. This market for defence robotics is forecast to reach $7.5bn globally before 2018, according to Global Industry Analysts. But with industrial robotics alone on course to tip $37bn by the same year, it’s in these markets that the real opportunities lie.

In China, sales of industrial robots last year surpassed 57,000, representing a 55 percent increase on the year previous and a quarter of global sales, according to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. China has already surpassed Japan as the largest consumer of robots worldwide, and Song Xiaogang, President of the country’s Robotics Industry Association, believes sales will continue to climb at a yearly rate of 40 percent.

With China’s younger generations shunning simple manufacturing jobs in favour of skilled work, and wages rising, robotics has been time and again proposed as a means of slashing costs and boosting productivity. The country’s dependence on labour-intensive factories also does a disservice to its aspiring millennials, and the introduction of robots could quicken China’s transition away from manually assembled products and on to advanced manufacturing.

Shenzhen Evenwin Precision Technology, a manufacturer of mobile phone components, unveiled plans earlier this year to construct a factory staffed almost entirely by robots as part of the country’s automation push. Based in China’s Dongguan manufacturing hub, the facility is to be built in answer to spiralling labour shortages in the Guangdong province, where an additional 600,000 to 800,000 workers are needed, according to the region’s Department of Human Resources and Social Security. Should the factory materialise as planned, many more could follow.

The International Federation of Robotics announced recently that, by 2017, China will have more robots in production plants than any other country. Yet quality remains an issue for a market consisting of mostly simple machines, and any person looking for a high-end model must take their search overseas. China’s robot-to-worker ratio is also short of its competitors at about 30 to 10,000, down on Japan’s 332 and South Korea’s 396. “Although Japan paved the way, South Korea now leads in the highest per capita density of robots, and China and Germany are following suit”, says Jennifer Robertson, Professor of Anthropology and the History of Art at the University of Michigan.

These figures have led some to speculate South Korea could soon threaten Japan’s dominance, with demand for industrial robots there tipped to reach the $2.3bn mark before 2021 and Korea’s Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy planning to finish up a $1bn ‘Robot Land’ project in 2018. And so, while China looks to build on its 3,200 percent bump in sales over the last decade, aiming to manufacture one third of robots before the end of 2015, South Korea has launched a half-decade-long push that will see it spend $500m each year.

For Japan, it’s not only in manufacturing that robots could relieve the pressure. Robertson says: “Abe is earmarking $24m toward the development of caregiving robots to augment a serious shortage of nurses, due in large part because of the impossibly rigorous exams (in Japanese) given to otherwise highly qualified Indonesian and Filipina nurses who wish to work in Japan. In terms of lucrative markets, Japanese robotics is now collaborating in the weapons economy, one of PM Abe’s new, and highly controversial, nationalist initiatives.”

The perfect fit

Superior robot-to-worker ratios and consumption aside, widespread claims that Japan’s robot industry is under siege are grossly overstated. Robertson says: “Where the Japanese can continue to lead is in the area of robotics spin-off industries, such as: new optical lens and haptic devices; new synthetic materials, from ceramics to artificial skin; surveillance technologies; modes of human-robot interaction, and so forth.” Japanese robot makers still account for some 60 percent of the market, China about a quarter, and the rest is made up of mostly European and American names. Add to that the country’s fitting demographic trends and generous government incentives, and it looks like Japan can only build on its leadership.

“Since the post-war period, Japan has pursued a policy of automation over replacement migration”, says Robertson. “Japan employs more industrial robots than any other country, and is the world’s biggest supplier of robots. That said, robots are still not advanced and versatile enough to do non-assembly-line work, and thus special visa arrangements have and are being made to recruit labourers from outside of Japan – China in particular.” The government has routinely allocated JPY 600bn ($4.9bn) to the field of robotics, though policymakers have recently committed to a budget four times that size in the hope it might usher in a new industrial age of machines. Failing that, the expanded budget will at the very least suppress the country’s worsening labour crisis, inasmuch as robots could both boost a shrinking workforce and keep watch over an ageing population.

With Japanese technology having lost ground to major international rivals in recent years (namely Apple, Samsung and Google), the rise of the robots could mean Japan retakes the spotlight. The country’s challenges leave it uniquely positioned to pursue robotics in a way others are less inclined to, and, should events unfold as predicted, we could well see the beginnings of a robot revolution.