Japan fights flooding from below the surface

Japan’s G-Cans storm drain is thought to be the largest of its kind, but even this enormous system may not be enough to protect the nation against increasingly frequent floods

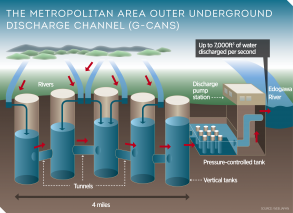

The G-Cans storm drain was built with the capacity to drain 7,000 cubic feet of water per second. This water is then pumped away from homes and businesses and into the Edogawa River

There is something cathedral-like about Japan’s huge underground storm drain. The G-Cans – or, to use its official title, the Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel – comprises a labyrinth of tunnels that stretch on for four miles in total, connecting gargantuan 213ft silos with a tank that is almost 250,000 cubic feet in volume. The sacred feeling of the space was not lost on its designers, who nicknamed this tank the Underground Temple.

The G-Cans was constructed in Kasukabe, a city some 20 miles north of Tokyo. Nestled 165ft below ground between the two cities, a visitor would have no way of knowing the mammoth storm drain was there. But this invisible system serves a critical function: the densely urbanised area is low-lying and has several rivers running through it, making it highly prone to flooding. The G-Cans was built with the capacity to drain 7,000 cubic feet of water per second – the equivalent of drying out an Olympic-sized swimming pool in just over 12 seconds. The water is then pumped into the Edogawa River on the outskirts of the city.

This invisible system serves a critical function: the densely urbanised area is low-lying and has several rivers running through it, making it highly prone to flooding

Below the surface

Every summer, Japan is battered by heavy rains and typhoons. These storms can cause extensive damage and loss of life. Among the most impactful in recent history was the 1959 Isewan Typhoon, which resulted in more than 5,000 deaths.

For decades, Kasukabe consisted mainly of farmers’ fields, which meant that any damage incurred by a flood was relatively minor on the national scale. But towards the end of the 20th century, Kasukabe became more urbanised and heavily populated as Tokyo expanded. It was in 1991, when a storm damaged 30,000 homes in the northern outskirts of the Japanese capital, that authorities were persuaded to invest in more protection.

Rain, rain, go away

As one of the most seismically active countries in the world, Japan has long been accustomed to investing in protection against natural disasters – even when the country was recovering from the Second World War, it invested six to seven percent of its national budget in disaster prevention. But the G-Cans was a project of unprecedented scale; having begun construction in 1993, it took Japan 13 years and a total of $2bn to finish, according to the BBC.

But now experts are asking whether even this gargantuan drainage system is enough to safeguard Tokyo. Historically, Japan has stressed earthquake preparedness over flood response, but flooding is becoming a more serious problem for the country. According to research by Yasunori Hada, an associate professor of regional disaster prevention at the University of Yamanashi, the number of people living in flood-prone areas in the country rose by 4.4 percent between 1995 and 2015. This was partly due to urban expansion, but it’s also the result of changing weather patterns.

According to estimates cited by the BBC, rainfall in Japan could increase by 10 percent over the course of the 21st century, most likely because of the climate crisis. At the same time, disaster experts warn that typhoons are becoming more frequent and more severe – for instance, when Typhoon Hagibis struck in October 2019, 200 rivers burst their banks, causing some of the worst flooding the country had seen in decades.

The Japanese Government is slowly waking up to the reality of this threat. In 2016, it added the Furukawa Reservoir – a two-mile-long tunnel that can hold five million cubic feet of water – to its list of flood prevention systems. But it’s still not enough.

As sea levels increase around the world, cities must address the threat of flooding with more urgency than ever before. Even though there has been huge investment into the G-Cans project, the fact that it alone is not enough shows just how costly it will be for Japan and other countries to build solutions that can match the threat level that flooding poses.