Repped to pieces: why firms need reputation management to survive

The economic crises of recent years, combined with the lofty expectations of consumers, employees and shareholders, has complicated the business of reputation management

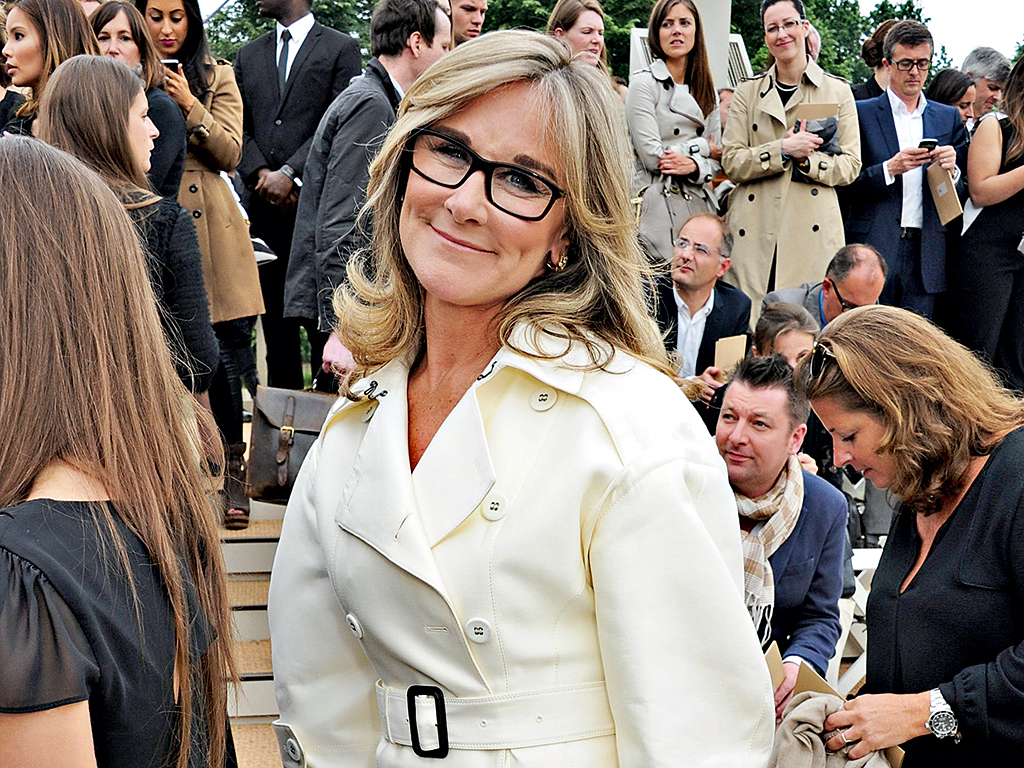

Queen of cool: Burberry's Angela Ahrendts has been credited for turning around the brand after it became increasingly associated with hooliganism

In the wake of allegations of war profiteering in 2003, the oil field services giant Halliburton faced fresh controversy when, in 2011, it was challenged by environmental authorities – the EPA among them – who claimed fracking could contaminate groundwater and impact local communities. In answer to the criticism, according to Fox News, a company executive took the opportunity over a keynote lunch speech to drink fracking fluid to prove its supposed purity.

The demonstration – of course – failed to offer any conclusive evidence of the sort, but does go some way to illustrate the lengths to which organisations are willing to go to mend a muddied reputation.

Reputation management

The turbulent economic conditions of the past half-decade and the resulting air of widespread mistrust has given rise to unprecedented challenges in the field of reputation management, as companies are subjected to closer scrutiny than ever before. Whether it stems from shareholders, consumers or taxpayers, the lofty expectations of the post-crisis world require companies to implement numerous and complex strategic measures to boost or restore their credentials.

[W]idespread mistrust has given rise to unprecedented challenges in the field of reputation management

“Succeeding with a good business strategy isn’t easy anymore,” says John Patterson, senior advisor at the Reputation Institute. “Growth is harder to come by, product launches fizzle out, the financial markets won’t cut you any slack, and even your employees say they don’t understand you. As a result of this loss of control, the gap between strategy and results has widened. You have more than enough information, and know that multiple channels are out there to be used, but you no longer have what you need to make confident decisions amidst the chaos and complexity that globalisation and commoditisation have wrought.”

Such was the problem for BlackBerry, a company pushed to the brink of extinction by rivals such as Apple and Google, who together rid the company of its once-impressive market share, damaging its reputation in the process. The present-day business of reputation management requires companies to explore all manner of strategic mechanisms – many of which did not exist until very recently – if they are to cement or restore trust between themselves and those affected.

“Gone are the days where a shareholder value mantra or a customer focus alone was sufficient. European multinationals must be trusted in order to garner enough support from the workplace to the marketplace to continue to operate sustainable businesses around the world,”says Patterson.

The post-crisis environment

The reputations of America’s big four banks – Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citi and Chase – suffered spectacularly as a result of financial losses and oversight. All are still struggling to rekindle consumer trust amid the ongoing financial fallout. Even after the immediate crisis, the American public’s trust plummeted: in October 2010, a Gallup study revealed it had hit an all-time low of 18 percent.

The overwhelming response of financial institutions, particularly banks, has been to ramp up regulatory compliance, corporate social responsibility and innovation – which appear to have yielded little in the way of results. Only last year, JP Morgan paid $920m in penalties relating to a $6.2bn trading loss, Wells Fargo forked over $42m to the National Fair Housing Alliance due to unlawful foreclosures, and Bank of America agreed to pay Fannie Mae upwards of $11bn relating to bad mortgages.

The fundamental misunderstanding here is that a steady rollout of schemes and initiatives will gradually heal any wound, which is just not the case. In order to redress the trust lost as a consequence of mistakes in years gone by, firms must instead redefine their foundations and instigate fundamental cultural change from within.

The unwillingness of consumers to forgive those most entangled in the financial crisis is best illustrated by the predicament of AIG. The insurance giant’s reputation was sullied when its role in the subprime mortgage crisis – involving billions of dollars-worth of unstable credit default swaps – became clear. The firm accepted blame, only to later accept a $130bn government bailout to fund its survival, while also failing to curb its executive bonuses. AIG’s reputation was tarnished to such an extent that, even after it assured the masses it had returned the entire amount to the government, many were still unwilling to forgive the company.

As an extension of the company’s reimbursement, AIG later introduced Negative Publicity Insurance, a product that acknowledges its past failings and seeks to right the reputational wrongs of those finding themselves in similarly sticky situations. The resulting product, ReputationGuard, gives clients access to experts at PR firms Burson-Marstellar and Porter Novelli to protect against reputational disasters. “In today’s world, one person’s negative opinion can quickly become adverse publicity on a global scale,” said Tracie Grella – the President of Chartis’ Professional Liability unit, the AIG division developing the product – in a statement. “Public perception of the response to an event can have a lasting impact on an organisation’s reputation.”

AIG is just one of many companies to have made drastic changes in response to past wrongdoings. Nike was chastised for exploiting adolescent girls, particularly in the manufacturing of their products. This prompted the Nike Foundation to establish The Girl Effect in 2008, to address poverty and lack of opportunity among young, female workers.

Reputation strategies

Financial services are disposed to bad reputations, but technology is usually at the opposite end of this spectrum. With its natural propensity for innovation and focus on customer service, it’s unsurprising many of the world’s most beloved brands are tech players. According to Harris Interactive, Amazon and Apple came first and second in the 2013 list of retail’s best reputations.

The evolution of the reputation environment, however, is far from a sum of emerging strategies, but rather the result of a wider cultural shift in the way consumers see companies. Corporates have taken more responsibility for the communities in which they work, and consumers now exercise more power than ever before over the way companies are run. Having said that, while these factors, along with the proliferation of media channels and the focus on action as opposed to PR spin, complicate proceedings, the underlying principles remain unchanged.

One key component of reputation management is brand reinforcement; consumers are quick to forget the relevance of a brand if they are not explicitly reminded why it is important to them. In the case of Audi, each ad comes with the tag line vosprung durch technic, reminding consumers of the company’s German heritage, conjuring associations with classic German engineering.

As an extension of this principle, marketers must consider brand segmentation when raising a reputation. The process of dividing and identifying market segments to meet a specific set of expectations is something that harbours the potential to boost or ruin a company’s fortunes. For example, Apple’s decision to introduce the iPhone 5s and comparatively cheaper 5c at the same time acknowledges the unwillingness of those in developing markets to fork out a premium for an Apple product.

Adequate leadership

Another factor that so often underpins reputational loss is the capacity of company heads to uphold the company image through turbulent times. “We’re clearly experiencing a crisis in leadership,” says Richard Edelman, president and CEO of Edelman, in a statement. “Business and governmental leaders must change their management approach and become more inclusive by seeking the input of employees, consumers, activists and experts such as academics, and adapting to their feedback. They must also pass the test of radical transparency.”

The relationship between business and consumer could not be further from the unquestioning dynamic that many assume it is. Regarding the responsibility of CEOs, they represent a company’s philosophy and strategic direction, so communication is key.

“From a process and relationship perspective, an organisation must not only know what they consider to be ‘doing the right thing’ it must also be ready to respond to changes in reputation through systems, processes and communications,” says Griffiths. Whereas the vast majority of company employees are given a specific role to play, the CEO’s job is far broader; they must ensure each employee and stakeholder is united in reaching a common goal.

Among the most impressive instances of a CEO-led reputational recovery is Angela Ahrendts’ turnaround of Burberry, which escaped ruin and went on to become one of the most successful luxury brands in the world. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, Burberry became increasingly associated with hooliganism, undermining the brand’s image of exclusivity and causing its credibility to plummet. Under Ahrendts, however, the company boosted its prospects through celebrity endorsement, social media and a formidable e-commerce presence.

Another effective company overhaul, this time instigated by Edward Whitacre, can be seen in the case of GM, when, after emerging from the shadow of bankruptcy, the firm embarked upon an aggressive reorganisation plan in 2010. GM discontinued and sold off numerous car brands, focusing on Chevrolet and Cadillac as the car manufacturer’s two driving forces.

Digital strategy

Frequently, new digital channels allow companies to communicate with disenchanted customers and give easy access to a proven method of righting past wrongs. For instance, when one of the Red Cross’s social media employees posted what was intended

as a private tweet on the organisation’s timeline, the company followed up with a humorous tweet. The two combined, rather than damage the organisation’s reputation, generated media attention and even received support from third parties.

On the other hand, social media allows the customer a direct line to voice their grievances. When one United Airlines passenger recorded a song explaining how the airline had broken his guitar, the video message went viral, denting the company’s share price. In the case of Airbnb, the property rental website has gone to extreme lengths to combat the negative publicity that can come with social media. The company offered $1,000 credit to one soon-to-be bride after her cottage accommodation was cancelled at the last minute, and even sent one guest a Pearl Jam T-shirt after she tweeted about a gig.

Beyond the realms of publicity, however, social media illustrates the ways in which relationship management has taken on a greater air of personalisation, demanding companies communicate with parties on an individual basis.

“Through a digital world, reputation is influenced and being influenced by engaged and connected stakeholder groups,” says Griffiths. “The realisation that reputation is both public and changing by the minute in the digital world has forced organisations to do two things; be responsive and ‘really be’ in reality the organisation that they could previously just have ‘claimed’ to be. Digital and online reputation has forced levels of accountability and transparency.”

There is no single method for successful reputation management. Rather, the responsibility lies with individual companies to identify what employees, shareholders and customers expect of them.