Start-ups can be more effective than financial aid

Non-profit investment funds could bring sustainable development and economic growth to some of the world’s poorest communities

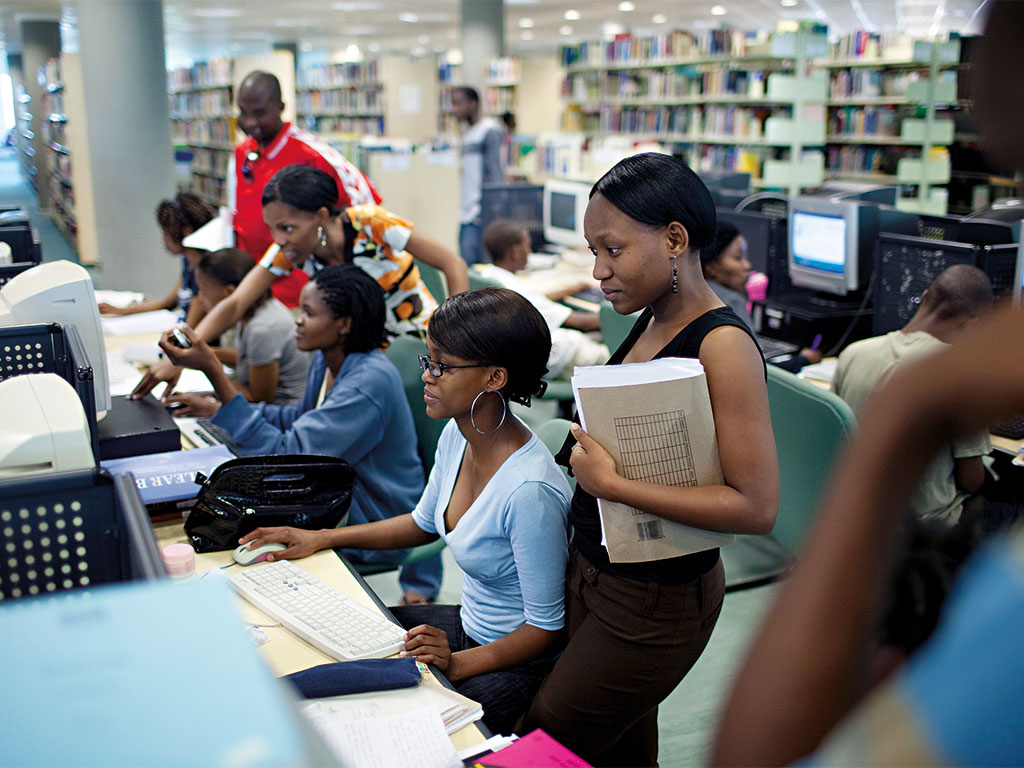

Encouraging and assisting an entrepreneurial culture can be an effective form of aid

In February, Unicef announced a $9m Innovation Fund, aimed at encouraging innovation among local tech start-ups and focused on improving the lives of vulnerable children in poor communities. Unicef will choose 60 start-ups from emerging markets (assessed on criteria including strength of team, relevance to children, and potential value in open-source intellectual property created) and give them approximately $50,000 each.

For the early-stage start-ups to be funded, they must fulfil one of three roles: create products for those under 25 years old to help learning and participation; provide real-time information for decision-making; or create infrastructure to increase connectivity, power, finance and support. Focusing the investment fund on youth products simultaneously boosts entrepreneurship in the tech industry and solicits benefaction to young people by providing proper education and other basic needs. Unicef Innovation fund manager Sunita Grote said: “We have seen that the products and services tech start-ups develop can increase access to information, opportunity, and choice for children and young people, including the most marginalised.”

Unlike conventional investments, the Innovation Fund will not take an equity stake in any of the start-ups; the UN said the ‘value’ will be in the projects’ ability to help others. Unicef Innovation Fund’s co-leader Christopher Fabian told Quartz: “We’ve created a hybrid between the world of venture capital and the world of international development, so what we do take is the intellectual property that’s developed by the companies that we’re funding and put it into the public domain.”

The need for innovative aid

Governments and NGOs have, in the past, been keen to provide disaster-response aid for short-term relief. Although their intentions are good, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that doing so doesn’t have any lasting economic impact. Rather, it can weaken governments and disable self-sufficiency within communities, making both state and communities dependent on aid. Over the past 60 years, at least $1trn of development-related aid has been transferred from rich countries to sub-Saharan Africa. And yet, real per-capita GDP is now less than it was in 1974, having declined over 11 percent. More than 50 percent of the population (over 350 million people) live on less than a dollar a day – a figure that has nearly doubled in two decades.

Start-ups largely have a positive impact on their local communities; not only do they reduce unemployment, but they can also (especially tech start-ups) increase skill levels and innovation

The emergence of development aid has largely focused on sector-specific projects, such as health, education and infrastructure, in an attempt to improve aid efficiency. It’s successful in supporting and sustaining specific areas of distress, but it doesn’t entirely overcome the problems of aid distorting markets, curbing entrepreneurialism and limiting self-sufficiency among beneficiaries.

Grote said: “As part of larger programmes built according to our Innovation Principles, technology can increase access to lifesaving information and services, and contribute to poverty alleviation. Investments in strong tech start-ups in developing countries help us build a community of developers and entrepreneurs who can build new solutions in the future.”

Unicef’s methods of combining venture capital investment and developmental aid may set a precedent for a new form of international aid. Entrepreneurialism and start-ups are not usually thought of as a form of aid, but analysing the socioeconomic ripple effect they have within communities and on economic growth suggests they should be.

Start-ups largely have a positive impact on their local communities; not only do they reduce unemployment, but they can also (especially tech start-ups) increase skill levels and innovation. These companies may not become the next tech giants, but SMEs tend to collectively make up a large majority of employment (globally, about 67 percent) and have a bigger impact on communities than large corporations. At the macro level, entrepreneurial activity stimulates economic growth. New innovation increases consumption, intensifies competition, and may even increase productivity through technological change, which translates into high levels of economic growth.

Start-ups have the potential to turn around lagging economies and even alleviate poverty in the most vulnerable regions. And yet, developing countries experience less entrepreneurship and start-ups than wealthier ones – not because they lack innovation, but because they lack capital. Unicef has recognised the ineffectiveness of aid, and the potential start-ups can hold for developing communities and economies. Investing in these regions as a form of aid can create opportunities, restore dignity to the receiver, and build long-term independence. Providing capital allows innovators to create ‘real’ value for their economies.

Philanthropic investors

This idea of ‘impact investing’ is not new. Companies and investors have become increasingly attracted to it; the ability to generate financial returns while making a positive difference to young entrepreneurs and their communities fulfils both commercial and moral desires. Ritchie MacDonald, Marketing Director at Truestone Impact Investment Management, said: “There are great opportunities in these markets as they are often fast-growing, but it is crucial to be selective, get to know the market in depth, and carry out the due diligence.”

Silicon Valley is shifting from its old methods of philanthropy and increasingly seeks to fund enterprise and innovation for social good. Pierre Omidyar, founder of eBay, was one of the first to adopt the entrepreneurial philanthropist approach, having deployed over $1bn of his fortune with the ambition of improving the world. Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, and his wife Priscilla Chan have committed 99 percent of their $45bn wealth to philanthropy through impact investing.

Recognising the promise in sub-Saharan Africa’s growing tech sectors, Silicon Valley has been funnelling its money into ventures from South Africa to Nigeria. Venture capital funding has rapidly expanded, rising from $40m in 2012 to $414m in 2014, and is projected to grow to $608m in 2018. Last year, start-ups raised $185.7m in Africa. Parallel to the boost in venture capital funding, sub-Saharan Africa’s economy has grown by 51 percent since 2005 – more than twice the growth rate of the global economy (23 percent) and four times that of the US (13 percent).

Many international aid organisations have made commitments to innovation, exploring new ways of alleviating extreme poverty and contributing to economic growth. Identifying a more dignified method of supporting developing countries and communities over traditional approaches is proving far more effective in cultivating sustainable and resilient development. MacDonald said: “Giving has an important role to play in many situations, however we believe that business generally offers a more sustainable means of creating change and transforming lives.”

Focusing on investing in new and inspired tech innovators could mean traditional aid will be surpassed by impact investing in the coming years. Aid in the form of investments will build fair, safe and equitable societies in the developing world. The combination of venture capital investment and developmental aid may set a precedent for foreign aid in the future.