The four countries most impacted by cashless payments

As secure cashless payments continue to become faster and easier to use, their popularity among consumers is changing the global economy. Here, we examine the countries most effected by this trend

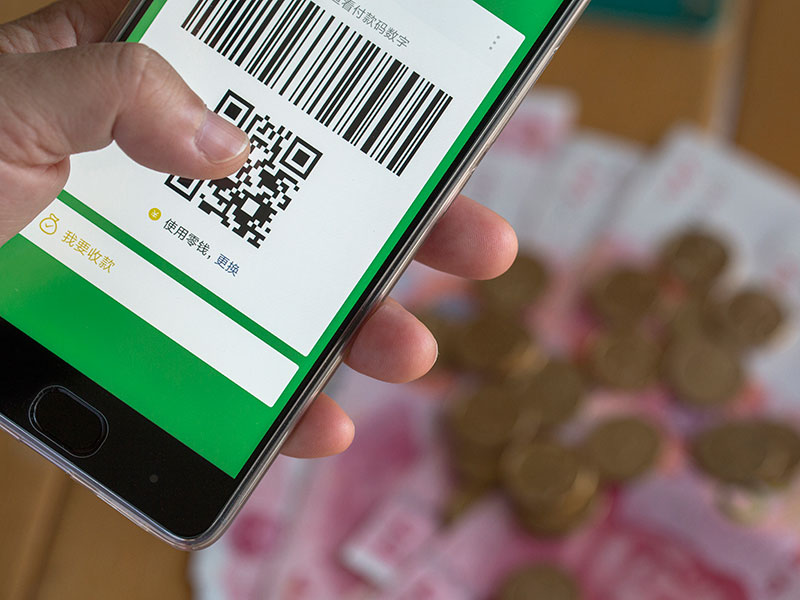

The QR codes scanned by payment apps have become common fixtures in shops throughout China, with vendors of anything from rental bikes to clothing embracing cashless payments

A ‘cashless economy’ used to refer to a society that simply bartered for goods but, in the modern day, the rise of electronic payment methods has made the exchanging of paper notes seem just as antiquated. Credit card payments and, more recently, online and mobile transfers have rendered transactions more secure, minimising the time spent queuing at shop tills.

A study conducted by ForexBonuses found Canada, Sweden and the UK to be the most ‘cashless’ countries in the world, with the analysis focusing on criteria such as the number of credit cards per inhabitant and total cashless transactions. But, away from these western states, new payment models are also having a dramatic effect in Asian and African economies.

Here, we outline four countries that have been economically and socially transformed by the uptake of cashless payments:

Sweden

Sweden has become the benchmark for cashless economies with more than 59 percent of transactions completed without physical money. According to Riksbank, there are 70 million fewer notes in circulation than four years ago; even local flea markets use Sweden’s homegrown mobile payment app, Swish, in place of cash, and it is impossible to buy a bus or metro ticket with physical money.

The increased opportunity for small businesses and the elimination of fraudulent hard currency makes cashless payments an attractive proposition

But the most dramatic change has been that of the Swedish finance sector. Swish, which identifies bank accounts via phone numbers, was created in collaboration with major banks including Swedbank, Nordea and SEB. By 2016, 900 of Sweden’s bank branches had stopped dispensing cash or taking deposits of it, with many removing their ATMs altogether.

Sweden’s forward-thinking banks have ensured its status as a leading cashless economy for over half a century now, having persuaded Swedish businesses to start paying their staff electronically in the 1960s – years ahead of other European countries.

China

Despite the government’s decision to ban cryptocurrencies last year, the Chinese population’s appetite for cashless payments continues to grow. The WePay and Alipay apps – introduced by Chinese tech giants Tencent and Alibaba, respectively – continue to dominate the market. In fact, mobile payments in China reached a whopping $5trn in 2016.

The QR codes scanned by payment apps have become common fixtures in shops throughout the country, with vendors of anything from rental bikes to clothing embracing cashless payments. The emergence of Didi, China’s answer to Uber, has also spurred cashless payments in the transportation industry, encouraging the use of mobile and online payment services in place of physical transactions.

Notably, this appetite for digital payments has also impacted neighbouring countries: the number of Japanese stores accepting Alipay doubled in 2017 in order to cope with the demand from Chinese visitors.

Kenya

The advent of virtual payments in Kenya some 10 years ago produced remarkable results. Mobile payment app M-Pesa was launched by Vodafone’s Safaricom to allow quick transfers of small payments via text message. The system proved overwhelmingly popular: it now has 30 million users, with 529 transactions processed per second in 2016.

A study conducted by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found the mobile payment service has also helped lift two percent of Kenyan households out of extreme poverty, equating to roughly 194,000 people.

M-Pesa eased transactions for local businesses and led to an estimated 185,000 women taking up business occupations in Kenya

Further, M-Pesa eased transactions for local businesses and led to an estimated 185,000 women taking up business occupations. The cashless economy continues apace as the 46-member Kenya Bankers Association plans to introduce a mobile payment platform to rival M-Pesa.

India

In a 2013 report, MasterCard concluded India was not properly prepared to take up cashless payments and, indeed, the past four years have witnessed a flawed transition. The government’s Cashless India initiative aimed to create a “digitally empowered society and knowledge economy” but it has achieved mixed results.

As part of the initiative, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a blanket ban on the highest denomination banknotes (500 and 1,000 rupee bills) in 2016. The Bank of India claimed this would curb the funding of terrorism through forged currency, but the snap decision caused a brief drop in GDP as panicked customers queued outside banks in their droves to deposit notes before the cut off.

Nonetheless, the push to deposit currency has recapitalised India’s banks and the Nifty 50 index, India’s benchmark stock market indicator, rose 30 percent in the first half of 2017. Meanwhile, the development of Aadhaar, a vast biometric database that assigns users a 12-digit identity number, has helped ease the transition. Introduced in 2009, Aadhaar has enabled many Indians with no identity records to open bank accounts and use cashless payment systems, easing secure payments for both individuals and international traders.

The race to go cashless inevitably has some disadvantages: principally, an entirely cashless system means people cannot hold capital outside of banks, putting them at the mercy of fluctuating interest rates. However, the increased opportunity for small businesses and the elimination of fraudulent hard currency makes cashless payments an attractive proposition, and the cashless revolution looks set to gain further sway in the near future.