The PR stunts worth more than the products they’re selling

Tech companies love nothing more than a grandiose display of their equipment, but the show is often more valuable than the technology

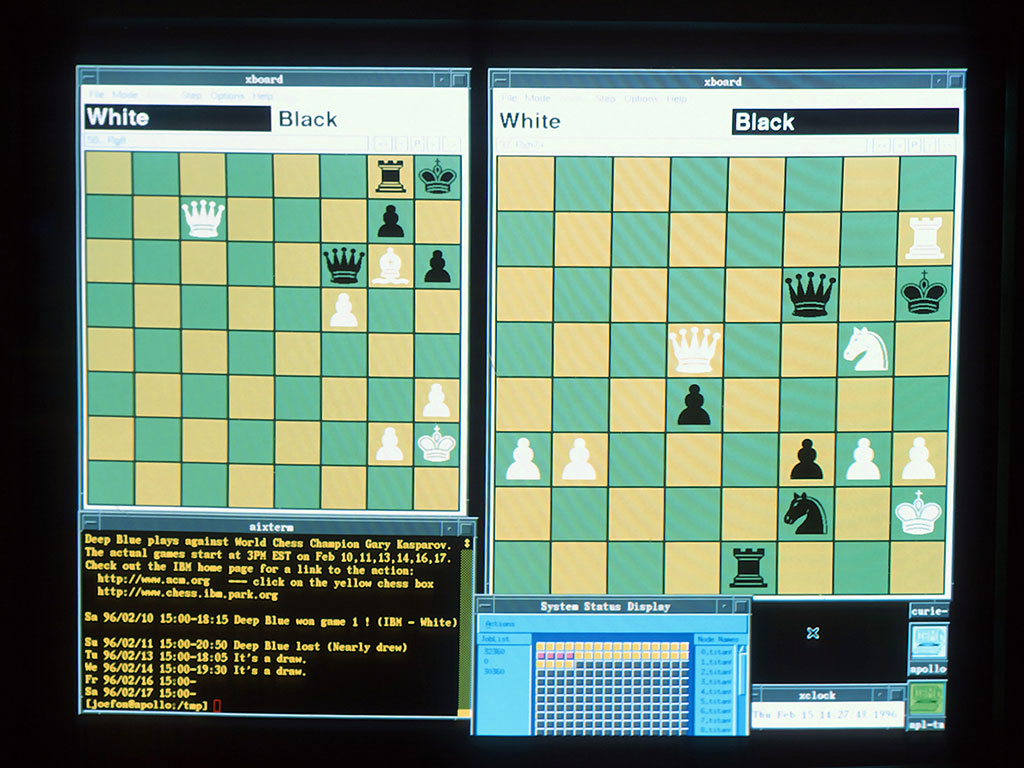

A screenshot taken during one of Deep Blue's chess games against Garry Kasparov in 1996. The computer ultimately beat the Grandmaster and ended up with a higher Q Score than the CEOs of Oracle and Sun Microsystems

In the late 1880s, the US was locked in a war of competing electrical standards: direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC). While Thomas Edison’s DC found initial success, it was difficult to convert to higher or lower voltages. AC, a technology refined by Nikola Tesla, didn’t have that issue and earned support from entrepreneur George Westinghouse. Not wanting to lose royalties from the patents he held on DC technology, Edison began a smear campaign against AC, claiming it was the more dangerous of the two standards. One of the more alarming ways he did this was through demonstrations to journalists of how AC could kill stray animals at lower voltages than DC.

Thankfully, today’s public displays of technology are far less barbaric, but remain just as useful and important. In fact, the inspirational, technical and scientific endeavours of a company’s bleeding edge technology may be worth even more than the products it actually sells.

These wild projects play a big part in the public’s perception of Google/Alphabet

Google was turned on its head last year when it was transformed into Alphabet. The new corporate structure revealed a lot more than was previously known about how much the company spends on its experimental projects: the ‘other bets’. These include products currently on the market such as the Nest thermostat and the company’s fibre optic internet service, as well as ideas that are still in the experimental stages, such as driverless cars, internet-delivering hot air balloons and contact lenses that measure glucose. Overall, the other bets had an operating loss of $3.57bn in their last quarterly revenue report. This might have investors worried if it wasn’t for the overall revenue of $17.3bn Alphabet posted, thanks to its highly successful advertising business.

Despite the losses they incur for the business, these wild projects play a big part in the public’s perception of Google/Alphabet as a leader in innovation. The corporation frequently ranks high in surveys measuring people’s admiration of companies, despite the vast majority of its business being in the comparatively dull field of online advertising.

Marielle Baylis is Account Director at Sketch Events, an experiential PR and stunt firm in England, whose staff are experts at large scale public marketing events. Some of the projects Sketch has worked on include the installation of a clockwork lion sculpture to promote National Geographic’s Big Cat Week and a 12ft sculpture of Mr Darcy for the launch of the UKTV Drama channel.

“The right PR stunt can earn a brand an awful lot of kudos and cool points if it’s done the right way”, said Baylis. “They can earn a huge return on investment and gain a lot of media coverage the world over when it’s paired with social media. PR stunts don’t necessarily sell a product, but they really bring an idea of that brand to life and heighten a brand’s visibility, its perception, and give a brand a personality.”

Google doesn’t have to spend money advertising its car business; the mere fact a self-driving car is being worked on is newsworthy in itself.

Shall we play a game?

The board game Go proved difficult for computers to master. There were just too many moves available to the player at any one time. The best human players make moves through gut instinct, finding patterns in the board they might not even be able to explain themselves. Since there isn’t a playbook, computers struggle to make the truly creative moves the best players use to win tournaments. This year, however, Google researchers cracked it with DeepMind, toppling Europe’s reigning Go champion, Fan Hui.

Investors will have to make do with that victory for now, but they have reason to hope they might get some financial return out of Google’s big artificial brain.

Work began on the chess-playing computer Deep Blue at Carnegie Mellon University in the 1980s, before its development team was hired by IBM in 1989. Continued work eventually led to Deep Blue defeating chess Grandmaster Gary Kasparov in 1997. While no doubt an impressive development in artificial intelligence, the publicity it brought IBM following the match was far more valuable.

It’s not a great look for a company when your rival built a server rack better known than your CEO

Three years later, long after what could have been the computer’s 15 minutes of fame, Marketing Evaluation/TvQ awarded Deep Blue a Q Score; a measurement of the popularity and recognition of a person, fictional or otherwise, among the public. Deep Blue became the first computer to earn one and was ranked close to Larry King, Carmen Electra and Carson Daly. Most notably, it rated higher than the CEOs of IBM’s rivals: Larry Ellison of Oracle and Scott McNealy of Sun Microsystems. It’s not a great look for a company when your rival built a server rack better known than your CEO.

It costs to be spectacular

The reason these technological achievements don’t appear more often is they aren’t easy. While the completed projects might be worth an incalculable amount in brand recognition, advanced technology is, by definition, hard to create.

A prime example is Honda’s Asimo. Development of the child-sized robot began in 1986 as a pair of unpleasant looking robotic legs that took up to 20 seconds to take a single step. Some 30 years later, Asimo can now run and jump. Development of the robot continues, though its appearance has remained largely unchanged since 2005, when it became a mascot for Honda.

While the results are impressive, you cannot buy an Asimo yet. Honda hasn’t broken out the cost of the project, but it is no doubt at least hundreds of millions of dollars. If Honda wasn’t such a large and successful company, investors would be furious at the seemingly huge waste. Still, President Barack Obama playing a short game of football with your creation isn’t an event easily organised without something spectacular. Besides, Asimo may still yet pay off in the long run; the recognition software developed to help the robot avoid obstacles and recognise people might make its way into Honda’s inevitable self-driving car.

The same could be said of Elon Musk’s proposed Hyperloop. The CEO of SpaceX and Tesla is well known for his investments into ambitious technology. His idea for a hyper-fast rail system spawned a recent competition to design something that fitted his brief. While he may not be implementing the design himself, his ambitious proposal and the construction of a test track is no doubt beneficial to his public appearance. You can’t write ‘Elon Musk’ without adding ‘CEO of SpaceX and Tesla’ (check out the top of this paragraph).

The greats of the technology sector are always forward looking, so it’s no surprise the companies are too. Though they may panic shareholders, big, expensive and highly experimental projects come with the territory, especially with today’s multibillion dollar companies. It’s a win-win no matter how you look at it: at worst, a company generates headlines for its impressive endeavours. But if an ‘other bet’ hits the jackpot, the returns can be enormous.