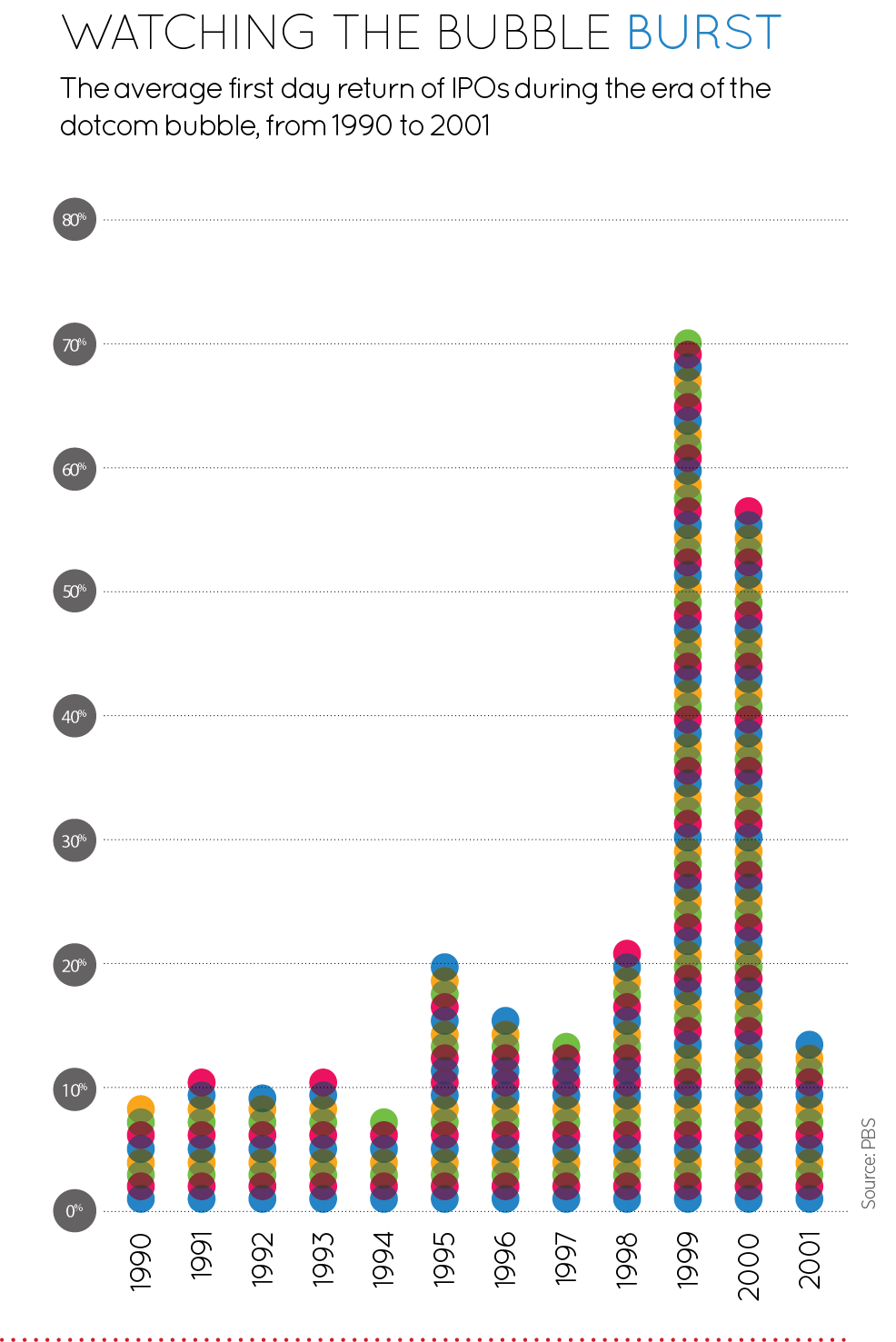

The history of the dotcom bubble – and how it could happen again

With tech companies growing at rapid rates, many commentators are worried the industry could be in line for a catastrophic fall – one comparable to the dotcom crash of 2000

Huge deals in the tech industry were originally seen as a force for good, but could have a horrendous backlash in years to come

Over the last couple of years, the tech industry has seen a number of colossal deals. From the $8.5bn Microsoft paid for Skype in late 2011, to the $22bn acquisition of messaging app WhatsApp by Facebook last year, tech start-ups have become hugely sought-after among investors. While many have been shocked by these huge valuations, the reality is the technology industry has been here before – and the last time it didn’t end happily.

From 1997 until early 2000, tech companies were the most exciting new investment to be made. As the internet increasingly became a tool for both businesses and consumers, and began to play a part in people’s everyday lives, a huge number of companies emerged, touting dazzling services that harnessed this brave digital new world.

Dotcom fever

The number of IPOs that doubled their prices in their first day:

2

1997

12

1998

107

1999

67

2000

0

2001

Source: PBS

Investors scrambled to give these new web-based companies money, hoping the returns when the start-ups floated would make them incredibly wealthy. In many cases, that proved to be the case, with the leaders of companies such as eBay, Amazon and Google gaining vast wealth and becoming titans of the tech community. Many others, however, weren’t so lucky.

When the dotcom bubble burst at the turn of the millennium, shareholders lost approximately $5trn. For such a new and exciting industry, the collapse was spectacular and brutal. Countless companies had come to market with supposedly revolutionary new technologies, all clamouring for attention: huge amounts of the investment funds venture capital firms were chucking at them were spent on marketing, expansion and, in some cases, lavish lifestyles. In other cases, they were simply not ready for market, with attempts to meet wildly unrealistic expectations doomed to failure.

When the collapse happened, between 1999 and 2001, large numbers of companies went bust and ceased trading. Others saw big declines in value, but somehow managed to cling on.

Is it happening again?

The concern in the industry that another bubble is forming has grown in recent months, with disappointing IPOs suggesting a slowdown in enthusiasm for tech stocks. However, if there is a bubble, it has been growing for longer than the two years it took for things to spiral out of control at the end of the last century. Many of the firms involved have been around for considerably longer than their late-90s counterparts, and have had time to build up more sustainable followings and infrastructure.

There is another key difference: many of the companies that became massively inflated towards the end of the 90s were publicly listed, meaning many of the creditors were regular investors seeking to profit from the tech boom. Today, the majority of the tech companies receiving big investment are privately held, and, while they are likely to eventually go public and give investors a return, they will probably have their valuations downgraded before doing so. And if they are overly leveraged and unable to get the IPO valuation and subsequent investment they require, then any collapse will be relatively isolated to the private markets.

Indeed, bigger players – be it Google, Facebook or Apple – snap many of today’s exciting new tech companies up long before they can reach their own IPO. This has been seen recently with Facebook’s acquisition of both WhatsApp and Instagram for seemingly inflated prices, as well as Apple’s purchase of Beats for $3bn.

Stephen Stanton-Downes, Head of Digital Implementation at consultancy firm Moorhouse, said many of these deals are defensive: “Facebook’s value proposition is dependent on it being the go-to for social conversations. At the time of the acquisition, mobile (smartphone) was taking off fast and Facebook’s own Messenger product was weak. Also, as can be seen from Facebook’s recent revenue growth, mobile advertising is pivotal and further strengthens the desire to buy out mobile social communications platforms that might present a credible threat.”

While some big firms tend to swallow up their new acquisitions, Facebook’s recent strategy has been to keep their brands distinct. “Leaving the brand of the acquired company intact attempts to minimise the likelihood of a mass exodus of customers”, said Stanton-Downes.

As the value of these deals increases and many tech firms look to IPOs to raise finance, many in the industry worry whether the strategy is sustainable. Stanton-Downes said it depends on the underlying business. “Some are sustainable and others not. Facebook’s IPO debuted at $38 per share in 2012 – the third largest in history. Today its share price is roughly $91. On the other hand, Zulily just sold to QVC for less than its IPO price – having spiked at near twice the initial offer price.”

Not all companies that emerged during the dotcom bubble collapsed; many of the most recognisable technology brands around today successfully navigated the choppy waters of that period. However, a number of firms that survived the crash did so with valuations much lower than those they had enjoyed at the height of the boom.

MarketWatch

$17

Opening share value

$9.75

Value at end of first day

$1.26

Share value in 2001

A recent Bloomberg article cited the example of MarketWatch. The business news website went public on January 17, 1999, with trading starting at $17 a share, before soaring to $97.5 by the close of the day. However, by 2001 the company’s share price had slumped to $1.26 a share. While it survived the crash, it was ultimately sold to Dow Jones & Co in 2005 at $18 a share. The company may have survived, but it required a hefty correction in valuation in order to do so.

Avoiding pitfalls

If today’s industry is to avoid a similarly painful collapse, the potential of new businesses is going to have to be realistically appraised based on market chances, rather than excitement over the technology they might offer.

“The internet allows for low transactions costs and low global distribution costs and hence huge leverage”, said Stanton-Downes. “Having said this, there are many tech companies attracting significant multiples based on the assumption they can use their same platforms to bring adjacent services to market; assumptions [that] may prove not to be valid in the long run. Uber, for example, is now valued at $50bn, even though it’s fighting a number of regulatory battles around the world.”

Investors need to take a similar stance when selecting which tech stocks to back. While a company’s technology might seem full of potential, without a business case, it is unlikely to deliver healthy returns, said Stanton-Downes. He cited the example of Twitter’s recent struggles to transform its vast user base into a profitable business. “Avoid the companies that aren’t making money or whose private equity multiples are crazy. Companies often use money from an IPO to scale, but if the business case is not there when the company is smaller, it’s not going to be there just because a company becomes bigger.”

While bubbles tend to be a natural feature of a market, the tech industry knows all too well just how damaging they can be. While it seems unlikely that the likes of Facebook and Twitter are due a collapse in value, history has shown that previously valuable stocks can collapse unless there is a strategy in place to ensure profitability.

Boohoo.com

Launched in 1998 by a group of Swedish developers, Boo.com was one of the highest profile casualties of the dotcom bubble. Based in the UK, the company was set up with the intention of creating a global online fashion store.

However, having secured considerable venture capital funding in 1998, Boo.com’s official website launch was repeatedly delayed; it eventually went live in the autumn of 1999.

Between its conception in 1998 and its eventual collapse in May 2000, the company managed to spend around $135m of its venture capital funding. This included expanding its initial number of staff from 40 employees in a small London office to 400 employees dotted around eight global offices.

Many reasons have been given for the collapse of the firm, from an overly aggressive expansion plan to constant complaints about the user experience of the website, but ultimately Boo.com was doomed because it got ahead of itself. It spent all its funding in a short space of time – just as investors were getting cold feet about tech firms – while the all-important sales failed to materialise. Investors lost millions, with just $2m recouped from the sale of its remaining assets.

Flooz.com

Flooz.com, a New York-based start-up that went online in early 1999, was the child of iVillage cofounder Robert Levitan, and one of the first companies to try and crack the online payment market. The platform worked by allowing consumers to use ‘Flooz’ credit on other e-commerce sites, such as clothing store J.Crew and bookshop Barnes & Noble.

Flooz.com spent considerable amounts on promotion, with expensive TV adverts featuring Hollywood actress and comedian Whoopi Goldberg frequently airing around its launch. The company managed $3m worth of credit card sales in the first year and $25m in its second.

Disaster struck, however, when the FBI informed the company it was being used by a group of Russian criminals to launder money. Levitan later admitted fraudulent activity at one point accounted for as much as 19 percent of all the transactions the site was processing. The damage to the firm’s reputation was done and Flooz.com collapsed in August 2001. It had used up all of its near $50m venture capital funding during its brief time in operation.

Pets.com

One of the first online retailers targeting pet owners, Pets.com launched in 1998 to considerable fanfare. A number of big name investors backed the business, including Amazon, which bought a 54 percent stake in the firm. Large sums of money were spent on a high profile marketing campaign (featuring a sock puppet), which included an extremely expensive $1.2m advert during the 2000 Super Bowl. Thanks to the wave of publicity, Pets.com managed to attract large numbers of customers, even though the management had done no market research prior to launching.

However, strong sales figures couldn’t make up for the huge amount of money the company had invested on infrastructure, including warehousing. With a revenue target of around $300m just to break even, the management expected the company would take between four and five years to achieve profitability. Generous discounts were offered to customers in an attempt to generate loyalty, but it meant the business was selling items at a 27 percent loss.

Despite an IPO in February 2000, enthusiasm for the stock collapsed over the course of the next six months. It came at the same time as a number of other dotcom bubble stocks collapsed, heightening the pessimism towards the business. Pets.com went into liquidation in early November 2000.

Inktomi

A software development firm that was launched in 1996 by UC Berkely professor Eric Brewer and graduate Paul Gauthier, Inktomi originally began life as an extension of a search engine designed at the university. It eventually became a provider of software solutions to internet service providers (ISPs), in particular the then-popular search engine HotBot. It would later develop the Traffic Server software, which was adopted by many big providers.

A series of acquisitions in 1998 grew the user base of Inktomi. These included shopping search engine C2B Technologies, as well as Impulse Buy Network and Webspective. The company also helped develop the ‘pay per click’ payment platform that is now used across the web. However, such an aggressive expansion strategy exposed the company to the dotcom bubble burst in 2000, which hit ISPs hard and wiped out much of the company’s user base.

At the height of the bubble, Inktomi was worth a staggering $25bn. This vastly inflated valuation was not sustainable, however, and merely reflected the over excitement of the time. Inktomi was eventually sold to Yahoo in 2002 for just $235m – a dramatic collapse in valuation over just two years.

TheGlobe.com

Launched in 1994, TheGlobe.com was one of the first forms of online social media. Founded by Stephan Paternot and Todd Krizleman, it was initially aimed at fellow college students as a chat room style communication platform. Soaring popularity led to the company securing $20m in venture capital funding in 1997, with the 23-year-old founders awarding themselves generous salaries of over $100,000 a year.

The firm became famous thanks to its IPO in November 1998, when it posted the largest first day increase in value in stock market history. It managed to raise $27.9m and increase in share price by 606 percent, giving it a market capitalisation of $840m.

Perhaps the lasting image of TheGlobe.com was one of a shiny-leather-trousered Paternot filmed in a Manhattan nightclub with his model girlfriend, boasting to a CNN journalist: “Got the girl. Got the money. Now I’m ready to live a disgusting, frivolous life.” Mocked as the “CEO in the plastic pants” by many, he became the poster-boy for dotcom millionaires.

In 2000, the bubble burst and the company’s share price was hit dramatically, with its value tumbling 95 percent to just $4m in 2001. The founders were forced out, cutbacks were made, and the rot set in. The company still exists as a shell corporation, but has no assets or operations.

Pixelon

Another company that got ahead of itself at the height of the bubble was supposedly high quality video streaming service Pixelon. The company became notorious for its lavish launch party in 1999, which cost $16m and featured performances from rock bands KISS and Dixie Chicks, singers Tony Bennett and Faith Hill, and even convinced rock band The Who to reform. The iBash’99 was held in October 1999 at the luxury MGM Grand Las Vegas hotel and casino. The event was supposed to be broadcast over the internet via Pixelon’s streaming technology, but the attempt failed, severely harming the company’s reputation.

Pixelon collapsed just one year later after it became apparent its technologies were not what its founder Michael Fenne had claimed. In fact, Fenne was actually called David Kim Stanley, and had previously been convicted of a series of stock scams. Stanley was reported to have arrived in California and been living out of the back of his car just two years before the launch of Pixelon. The company started to sack employees in 2000, before being forced to file for bankruptcy.