More plastic could help create a circular economy

As consumer demand increases and more companies pledge to use recycled materials, a plastic paradox has surfaced. Now, more plastic needs to be collected to meet the rising demand for eco-friendly materials

If companies want to switch to recycled materials, a considerable amount of recycled plastic is needed, which is currently not available on the market

Plastic is a valuable material with good versatility. Its value, however, is lost if it’s not treated correctly throughout its life cycle. While consumer awareness grows, governments continue to set regulations to reduce plastic consumption, and companies around the globe are responding with commitments to use recycled materials in their products and packaging. However, this increased demand has created a plastic paradox: there isn’t enough plastic being collected and recycled to meet fresh demand and preserve the planet’s non-renewable resources.

A resource revolution is needed to solve this problem. The planet’s resources are limited, and a new strategy is required to create a circular economy.

Rethinking the system

The amount of plastic waste being produced is growing rapidly, and society’s failure to return plastic into a closed loop is having a negative impact on the environment and on our health. The current linear model means the end of life for plastics is mismanaged, and a valuable resource is lost in the process.

Consumer expectations for recycled plastic have increased due to the wave of information relating to the harm that misused plastic is causing. In response, governments and companies are making pledges to use recycled plastic. EU member states, for example, have signed several legislative proposals on waste, including an aim to hit a recycling rate of 70 percent for packaging waste by 2030.

Plastic has become public enemy number one, but it doesn’t need to be: if the management of plastic were to be improved, consumers would value its versatility more

The European Commission recently announced that plastic drinking bottles must include a minimum of 35 percent recycled content by 2025, while member states must collect and recycle 90 percent of beverage containers. Fast-moving consumer goods companies like PepsiCo and Unilever have pledged to increase recycled content in their packaging to 25 percent by 2025, while German company Werner and Mertz has shown even greater ambition, aiming to use 100 percent recycled materials for 65 percent of its packaged products by 2025.

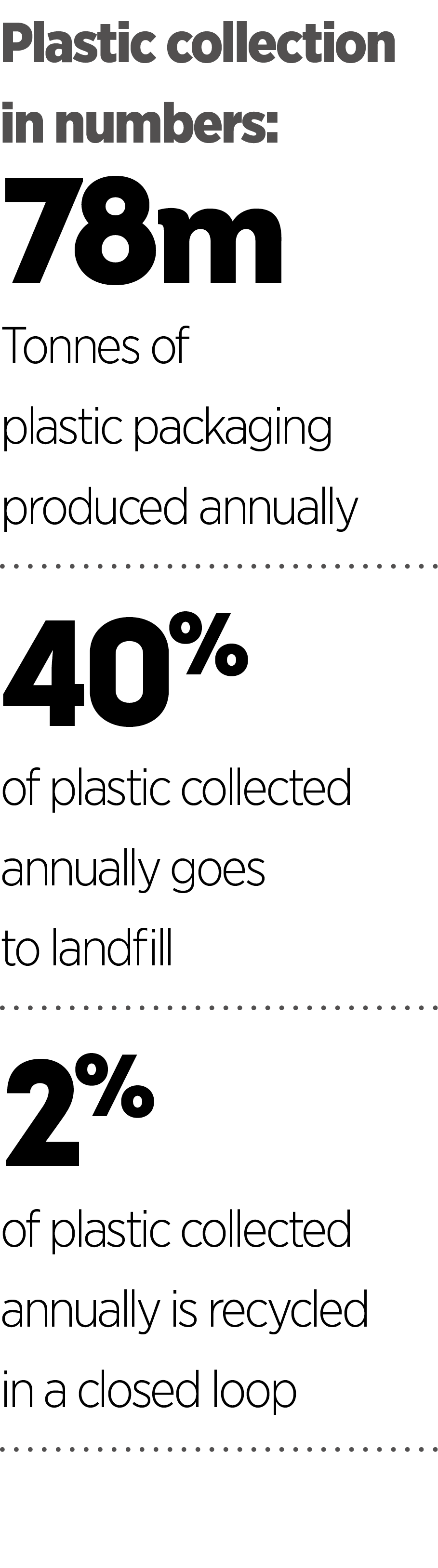

These pledges are ambitious and to be admired, but without a system in place to collect and sort the plastic, the paradox remains. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, of the 78 million tonnes of plastic produced annually, 40 percent goes to landfill, 32 percent becomes litter and harms nature and 14 percent is incinerated. While 14 percent is collected for recycling, only two percent of this remains in the circular economy.

The paradox is amplified by the fact that eight percent of the plastic we do collect is downgraded, meaning it can only be used once more and then does not remain in the circular economy. Essentially, the entire value is lost.

If companies want to switch to recycled materials, a considerable amount of recycled plastic is needed, which is currently not available on the market. Plastic manufacturers need a constant supply of recycled material; to create a circular economy, the system needs to change.

Revitalising recycling

If society is going to meet its recycling ambitions, we need to catalyse the circular economy. At the heart of this is the need to view plastic differently – not as waste, but as a valuable resource that is worth collecting. We need to make sure plastic stays in a closed loop through better management of its life cycle.

Everybody knows the adage about square pegs not fitting in round holes. The same can be said for a linear design for a proposed circular economy: no matter how you try and force it, it won’t work. Plastic packaging must, of course, maintain its current function to protect and communicate information about the product inside. If packaging isn’t fit for purpose, it can’t protect the product it is designed for, and the environmental and financial costs only increase.

Manufacturers must design packaging for the circular economy in a way that allows it to be easily recycled by not mixing it with different types of plastic, making the recycling process needlessly more complicated. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s 2017 New Plastics Economy report suggested that 30 percent of plastic packaging needed fundamental redesign and materials science innovation. A further 20 percent could incorporate better design for reuse.

Using recycled materials saves resources and lowers carbon emissions. It takes 60 percent less energy to manufacture recycled polyethylene terephthalate plastic bottles compared with bottles from new plastic, but despite this fact, not enough recycled materials are finding their way back into a closed loop. Manufacturers and brand owners with commitments to use recycled content must optimise and identify ways to increase the amounts of recycled material they use if they are to meet their targets.

Creating value

High-profile campaigns in the media have brought plastic waste to the forefront of our collective environmental conscience. Plastic has become public enemy number one, but it needn’t be: if the management of plastic was improved, consumers would value its versatility more. We must remove single-use plastics that belong to the linear economy.

There needs to be a collection system – possibly enforced via legislation – that encourages and incentivises consumers to put the plastic we use into the closed loop. Such a system would help to educate consumers, change habits and transform industry while ultimately providing plastic with greater value.

Deposit return schemes (DRS) are proven systems that encourage consumers to recycle their plastic drinks containers and increase collection rates, while also maintaining the purity of the material. Eight EU nations now have a DRS, with Germany leading the way with a 98 percent return rate. In Lithuania, TOMRA’s innovative reverse vending machines enable the automated collection of beverage containers and saw collection rates soar from 34 percent in 2016 to 92 percent by 2018.

In the current linear system, plastic with value is being lost. Mixed-waste collections, which include plastics that could be recycled in the same way as those collected separately, often end up incinerated or sent to landfill. This needs to be remedied, and the technology to do so already exists.

Optical sorting machinery, currently used in countries like the Netherlands and Norway, enables plastic to be recovered from mixed-waste streams and kept in the closed loop. The recycling industry must adopt better technology to prove to brands that materials recovered from mixed-waste streams can meet their requirements. Once collection rates increase, it must be recycled at the highest quality to make sure it can be used in new products.

Quantity and quality are needed to solve the plastic paradox. As the quantity of recycled material in the loop increases, the mindset of the industry must turn to quality. Using the best available technology for the processes of sorting, washing, extrusion and decontamination of the materials will be essential to achieve the desired quality levels for reuse. Increased use of recycled plastics reduces the demand for new material in many applications, thereby closing the loop further.

A circular economy for all

The plastic paradox can be solved, which is why TOMRA has set ambitious targets to accelerate the implementation of the circular economy and drive the industry forward. We aim to increase the global collection of recyclable plastic from 14 percent to 40 percent, as well as increase the recycling of plastics in closed loops from two percent to 30 percent by 2030.

Redesign and recycling will go some way to achieving this, but the main challenge is to work together to improve plastic collection and change the system. We cannot do this on our own; a collaborative value chain across industries is what’s needed.

We are dedicated to increasing the recycling rates of plastic and many other materials, and have been developing solutions since 1972 to do this. Our newly formed Circular Economy team is devoted to enabling the circular economy by working with manufacturers and retailers.

The desire from governments, companies and consumers to find the solution to the plastic paradox and plastic waste is present and growing. TOMRA’s resource revolution calls on everyone to recognise plastic as the valuable resource that it is, and use it to catalyse the circular economy. In doing so, we hope to contribute to improving the health of both the

planet and society.