The dark net protects our civil liberties

Authorities claim mass surveillance is a necessary evil in order to protect citizens. Are they right?

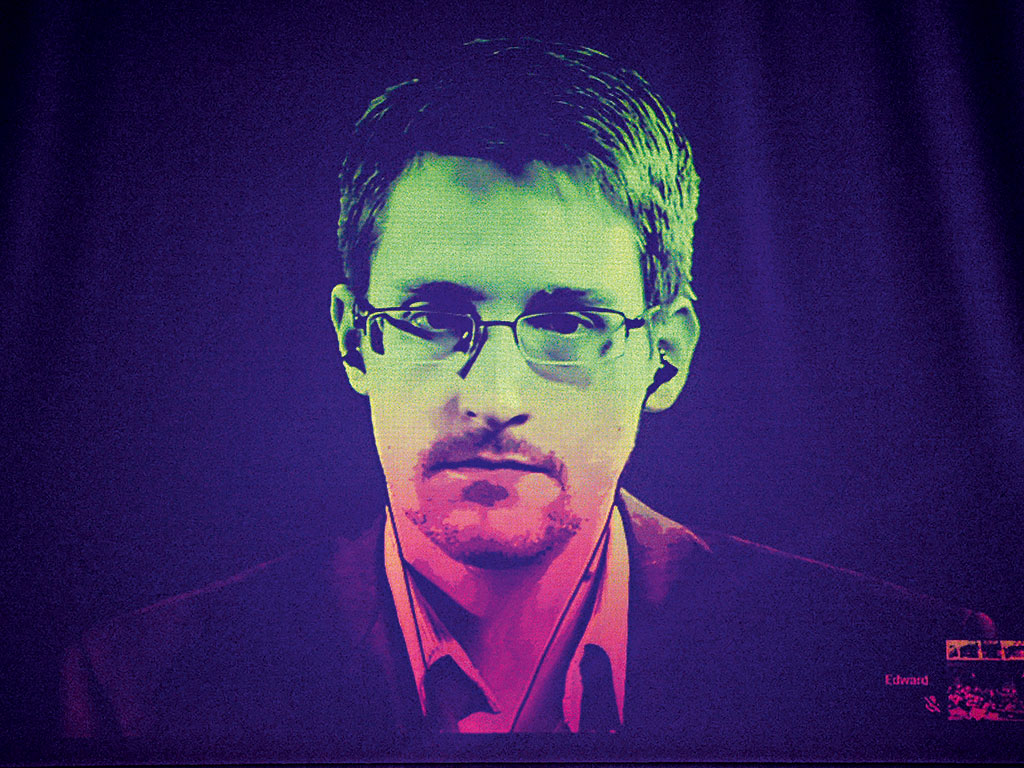

Former NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents revealing the extent of US and UK government surveillance

Long-distance communication was the result of one man’s agonising heartbreak. In 1825, while working away from home in Washington DC, Samuel Morse received a letter. In it, his father explained that Morse’s wife had suddenly become unwell and passed away. On hearing the news, Morse left for his home in New Haven, Connecticut, but by the time he arrived his wife had already been buried. Morse’s anguish over the fact that he was left in the dark while his beloved’s health waned led him to passionately pursue alternative methods for relaying information. Eventually, his imagination stumbled upon the idea of what would become the telegraph: the world’s first tool for high-speed communication.

89

Countries in which the Tor Network has servers

Humans are social animals. We desire connection with each other. We crave it. It is this need that has driven many of our greatest advances in communication. It is why, in such a relatively short time, our means of relaying information has developed from the humble telegraph in the middle of the 19th century to the inception of the internet at the end of the 20th. When Morse created the telegraph he ensured others would not have to feel the pain he felt. It was an invention that improved our world for the better. In the same way, when the internet was first conceived, it was seen as a force for good: one that would enable greater freedom.

“The dream behind the web is of a common information space in which we communicate by sharing information”, says Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the man who invented the World Wide Web. “[But] there was a second part of the dream too, dependent on the web being so generally used that it became a realistic mirror (or in fact the primary embodiment) of the ways in which we work and play and socialise.” He believed that, once our interactions with each other made it online, “we could then use computers to help us analyse [those exchanges], make sense of what we are doing, where we individually fit in, and how we can better work together”. He got what he wanted it would seem, but definitely not in the form he envisioned.

Tapping the web

Today, computers analyse our every move on the web in order to make sense of our actions. These machines once did this in secret, but thanks to the whistleblower Edward Snowden we now know that the US National Security Agency (NSA) and the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) are the ones behind this mass analysis; with the NSA’s massive data centre in Utah capable of collecting and storing every last byte of our personal information on its huge hard drives. As a result, the internet is now embroiled in the greatest controversy of its short life, as governments turn a technology that was meant to bring us greater freedom into a tool for keeping an ever-watchful eye over their citizens.

Due to the way most people connect to the internet – via a Wi-Fi connection – many do not completely understand how the data they send gets to its destination. To play video games on your Xbox One or post a picture of your night out on Facebook requires a vast physical network of cables that provide the backbone of the internet’s infrastructure.

Modern fibre optic submarine cables are the foundations for of this information super-highway and are installed along the seabed, linked together by an array of land-based stations, which then carry digital information to their designated destinations. One such destination is Cornwall, on the west coast of England. The cables that come ashore there carry approximately 25 percent of all internet traffic, and, unsurprisingly, it is also the home of GCHQ Bude. This satellite ground station is responsible for intercepting and analysing all the data that flows along these cables. It does so using what is known as fibre tapping. This is a technique that allows intelligence services to extract any and all information passing through the optical channels without interfering with the signal, thus avoiding detection. That was until June 2013, when The Guardian, with information supplied by Snowden, revealed the extent of the surveillance efforts by US and UK authorities. But what made the revelations even more shocking was the method in which data analysis was being carried out.

Running the numbers

When the average person imagines the secret services engaging in surveillance they imagine it being done by a team of people working meticulously day in, day out to analyse and make sense of all the data that flows through the internet’s fibre optic pipelines. In reality, that would be impossible because of the sheer size of the datasets being dealt with. Each day we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of data, a number hard to wrap your mind around. In order to make some sort of sense of it consider this: we now produce such an abundance of information on a daily basis that 90 percent of all the information in existence has been created in the last three years. So just how do the NSA and GCHQ manage to sift through all that? The answer is algorithmic surveillance.

Computer algorithms, not human beings, are responsible for sifting through all the bits and bytes. They are programmed to flag individuals based on certain criteria. For example, an algorithm may flag an individual who is caught searching certain terms the government deems dangerous or warranting further investigation. But there is a big problem with allowing computers to be responsible for picking out potential enemies of the state.

Data-rich algorithmic models such as the ones employed by the NSA have some serious limitations when attempting to correctly identify possible criminal or terrorist activity because of the way in which they are programmed to screen data. Algorithmic surveillance looks at all our mesa and metadata, watching everything from our emails to what words and phrases we search for on Google. They do so in order to build a profile based on parameters the government decides are potentially dangerous or worthy of suspicion. If a pattern that matches those criteria is found, it is flagged and then passed on to senior officials who can then take a closer look at what it has found. But algorithms have limitations. They are good at mapping what, when and where we are doing things online, but not necessarily very good at figuring out why. The fact algorithms have the potential to make false correlations from the mountain of information they screen should be a concern.

If you log onto Facebook or browse eBay there will be a host of advertisements in web banners that display products and services tailored to you. They are based on the information gleaned by the same types of algorithms employed by government » surveillance services. While many may be relevant, we have all encountered advertisements that make tenuous assumptions based on our online activities: ones that in no way relate to our consuming habits.

This may be harmless, because it is just marketing. But algorithms are also used to make decisions that have a greater impact on our lives. Individuals’ credit scores depend on algorithms; so does the manner in which people are treated when they travel through customs at the airport. But most worryingly of all, the US Government uses algorithmic surveillance to determine drone targets. Innocent people have died, in part, because of these complex mathematical models. In December 2013, the UN demanded the US disclose what its targeting protocol was after a fatal error killed 16 civilians in the al-Bayda province of Yemen. They were attending a wedding. Even though algorithms get it wrong, they are still used because there is no other way to satisfy the appetite the US Government has for sifting through the vast petabytes of information flowing through the internet.

Off the grid

Governments justify their obsession with our personal information by claiming it is a necessary evil that prevents acts of terrorism – but mistakes are clearly made. The other defence for this intrusion into our personal lives is that it is vital in combating cyber-crime, but activity of this kind does not take place on the same version of the internet that harbours cat pictures and viral videos. It occurs on what is commonly known as the ‘dark net’, where users are anonymous and the data they exchange with each other is almost impossible to track.

Access to the dark net is permitted through a piece of software known as a Tor Browser, which works in much the same way as Google Chrome or Mozilla Firefox, with one small difference: “It’s actually a browser to access the full internet – you just do so anonymously”, explained Andrew Lewman, Executive Director of the Tor Project, in an interview with the BBC, “and it puts the user in control of if they want to deanonymise themselves, to log into places like Google and Facebook. The Tor Network is a network of about 6,000 relays, which are servers spread around 89 countries or so. And what we do is relay your traffic through three of these relays in sort of a random order, so that where you are in the world is different to where you appear to come from.”

Due to the anonymity the dark net provides, it is a hotbed for illegal activity. It is the home of child pornography and black markets selling everything from fake IDs to stolen credit cards. There are even areas of it where users can pay to have someone killed. The largest markets, however, are concerned with the buying and selling of illegal drugs, and there are a number of reasons for this. The most obvious is the virtual market is far safer than its physical counterpart: both sides are able to remain anonymous and the deal is not done on the street, reducing the potential for violence. Direct transactions also cut out the middleman, which ensures the product’s purity remains high.

The Silk Road 2.0 was one of the largest marketplaces for the buying and selling of illegal drugs, until authorities closed it down in November. Those using the site thought they were beyond the grasp of law enforcement, until the US National Crime Agency released a statement that it had dealt a major blow to the dark web: they claimed they were able to locate the technical infrastructure of a host of illegal sites enabling them to shut them down. But rather than delivering a knockout blow, this instead proved to be a small set back.

Anyone who is familiar with illegal video streaming sites will know how, as quickly as the authorities can locate the servers to shut one down, within a few days an identical site will have popped up to take its place. The authorities are fighting a losing battle. The dark web is a game of cat and mouse, where the law enforcement will always be reacting and, therefore, always one-step behind.

Why we wear a mask

But the dark web and the Tor network are not just a cesspit for criminals; they are also a safe house for whistleblowers, journalists, activists, and those who just want to control their personal data. “Tor is spun out to be some big bogeyman to scare people”, Lewman told the BBC. “However, the average person is mostly worried about spreading their information online, unscrupulous advertisers taking advantage of leaked data… and for the same reason that you close the door to go into your house, some people just don’t want to leave a trail of data where they’ve been on the internet.”

Anonymity is a mixed bag. On the one hand it leads to drug dealers and paedophiles being able to get away with their illegal activities. But on the other, as in the case of the documents Snowden leaked, it acts as a safeguard, protecting our civil liberties, or at least allowing us to be aware that they are being threatened. The vast majority of us do not use the internet for malicious purposes, but just because a number do, does that justify mass surveillance programmes such as the ones carried out by the NSA and GCHQ?

“If we want to change the way that mass surveillance is done, encryption, it turns out, is one of the ways we do that”, said computer security researcher Jacob Appelbaum in the BBC documentary Inside the Dark Web. “When we encrypt our data, we change the value that mass surveillance presents.” But this cryptographic technology will only be developed and refined if we create a market for it. It is time to make our voices heard. The sanctity of the internet is something we all have a stake in. It is time we hid ourselves.